Remembering Lem Winchester

John Chowning,

George Lindamood,

and David Arnold

Introduction

Ed. note: On December 9, 2010, just prior to the publication of this article, David Arnold, bassist in the John Chowning Collegiates, died of cancer after a short illness. In spite of diverging career paths and geographic distance, the three Collegiates had remained in contact for over fifty years, making this article possible. Reflecting on Arnold, John Chowning wrote, “What David meant to me: His aesthetic sensitivity was a wonderful complement to mine in music and far beyond in image and imagery. Then all of the other of his attributes that were part of our deep friendship — sense of humor, interpersonal honesty...and authenticity! I had always the sense that he was the person that he would always be, one who could turn both stuff and people into poetry.” Although he chose a career outside of music, Arnold remained a musician and experimented throughout his life. His wife Lesley wrote that “He derived much pleasure from music and had an innate talent for playing almost any instrument he picked up,” and George Lindamood recalled, “The summer of 1957, when we played in Wilmington, Dave occasionally tried his hand at scat singing. He was pretty good at it, but not at all confident, so he rarely did it at public performances, just rehearsals. On the other hand, I wouldn’t have been caught dead doing something like that, and I think the same goes for John.” His taking up the saxophone in his seventies was simply another example of how music and learning were integral parts of his being. Special thanks to Lesley Arnold for assistance in completing this article, which now stands as a tribute to both David Arnold and his old friend Lem Winchester.

Lem Winchester Discography

Generated on Sat., Sept. 24, 2005

Date: UnknownLabel: [private recording]

Lem Winchester (vibes)

| a. | (unknown titles) (Composer Unknown) |

Notes by Ira Gitler to Winchester Special:

In 1958 Leonard Feather heard a tape of Lem Winchester and as a result presented him to Saturday afternoon’s audience at the Newport Jazz Festival that year.

Unknown whether tape survives.

John Chowning, January 9, 2008

George Lindamood brought to my attention all the unknowns in that opening entry in the discography of Lem Winchester, above, compiled by Michael Fitzgerald. What follows is an attempt to fill in those lacunae. [1]

Of first importance, the recording is known, and it still exists in several copies: treasured memorabilia in the possession of David Arnold, George Lindamood, and myself, as well as families and friends. The three of us were the John Chowning Collegiates, the college group with which Lem made his recording debut. [2]

The recording is important for two reasons. It is, as far as we know, the first time Lem was recorded. And it was through hearing this recording that the late Leonard Feather was moved to present Lem at the 1958 Newport Jazz Festival, an appearance so successful that it ultimately convinced Lem to give up his career as a police officer and become a professional musician.

One can speculate whether Lem’s extraordinary talent would ever have been “noticed” at the level where it mattered if the recording had not been made. Perhaps not. Lem impressed us a man whose first love in music was the playing of it, not being a “name” in it. He had, we thought, more ambition for his notes than for himself.

At the time of the recording (late summer, 1957) Lem was a successful officer in the Wilmington, Delaware, police force, assigned to what we now can call the African American community, where he was beloved by its inhabitants. The options for a smart and intelligent African American then were limited, especially one with a wife and young children. It was Lem’s mother, knowing that a police officer was at the pinnacle of power in her community, who persuaded him to join the police force in the first place. And she later was able to convince him to remain with the force, rather than joining his teenage friend and trumpet player, Clifford Brown, in the professional jazz scene.

Nevertheless, playing opportunities for Lem were many; sitting in at jazz clubs with touring musicians and playing at other local venues with his own quartet. In 1957 the Collegiates’ summer gig was playing at a Wilmington restaurant and bar called Marshalls. Monday nights were jam sessions open to all, and that is how we got to know Lem — first with his quartet and then, solo, as he sat in with us on other nights that followed.

To all of us Lem seemed content in a rewarding and stable career as a policeman — enriched by his stunning music on the side. He was revered by his community both as a police officer and by those who knew his music: he was welcomed into every musical setting he encountered.

What were the circumstances that led to this first recording?

Through a distant family member who worked for RCA, my father, James Reid Chowning, arranged for studio time with a recording engineer at the RCA sound studios in New York City. The date was a Sunday late in that summer of 1957. Lem drove up separately; because of other commitments he would be available to us for only a few hours. So we recorded Lem’s cuts first.

During the following school year Dave, George, and I selected the tracks that would be included in a limited pressing of The John Chowning Collegiates, an LP that would be sold through the Wittenberg College (now University) bookstore. Of the seven — possibly eight — original cuts featuring Lem, we included six in the final LP. Our limitations, not his, were the excluding factors.

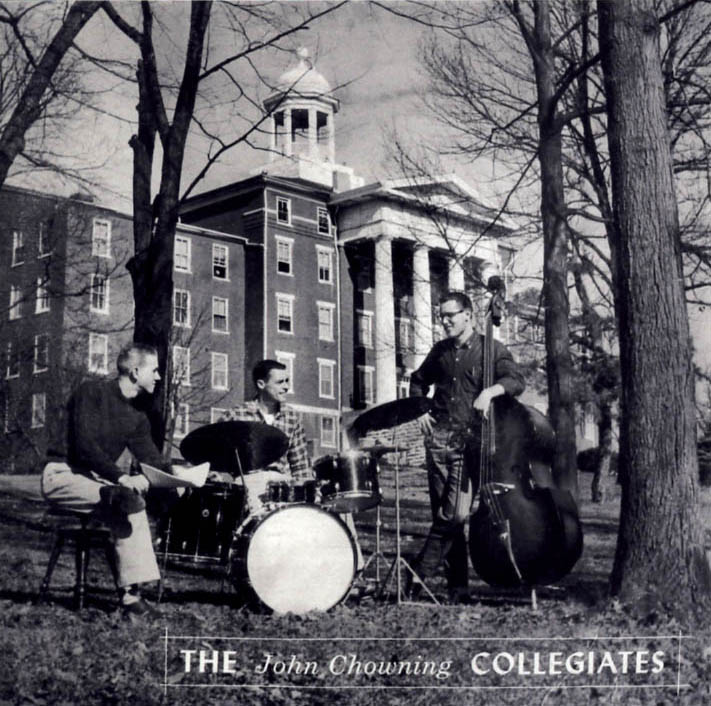

LP front cover (l-r): George Lindamood, John Chowning, Dave Arnold

photo by Dick Ballentine.

In the spring or summer of 1958 my father, always our most unabashed supporter and spokesman, sent the LP to Leonard Feather. Although I do not recall extensive conversations about this with my father, he surely hoped that our trio, with Lem, would be invited to perform at the Newport Jazz Festival. He was disappointed, I am sure, when the invitation came to Lem alone, but the three of us were not surprised. We were good enough players to recognize that Lem was a truly great jazz talent.

To my father’s credit, he maintained contact with Lem during the transition from police officer to professional jazz musician, and it was through him that the three of us learned of Lem’s tragic death in 1961.

Here are a few other recollections of Lem:

- He and Clifford Brown studied together with an “old tenor player” — possibly Robert Lowrey.

- He had great personal warmth and charm — I never saw him angry.

- When he played he would often snap his head sideways in a curious manner, much as girls do in traditional Balinese dance.

- He called the music he played with his quartet “down home.”

- After greeting and shaking hands with bassist Charlie Mingus at a jazz club in Philadelphia, Lem told me it was “like shaking hands with ten miles of bad road.”

George Lindamood, November 16, 2007

In the summer of 1957 the John Chowning Collegiates — consisting of John Chowning on drums, Dave Arnold on bass, and yours truly on piano — were playing six nights a week at Marshalls Restaurant in what was then (it is an abandoned derelict now) the Merchandise Mart on Governor Printz Boulevard on the northeast side of Wilmington, Delaware. In a way we were actually the Collegiates minus one because for our college-area jobs we featured a tenor man, Don Rossicka, an older fellow. But he had had to remain behind with his family and his day job at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton. Business was slow on Monday nights at Marshalls, so we hit on the idea of inviting other musicians in for a jam session.

I do not remember the first time Lem showed up, but John had mentioned he was coming and had told us a little bit about him. For one thing, there was that policeman business and the fact that he would have to cut out fifteen minutes early to go on his beat. I do remember that Lem wore a gray sports jacket over his uniform so it would not be obvious that he was a policeman, but we kidded him about his regulation shirt, a shade of blue considerably darker than what was fashionable for business dress in those days. And then there was the bulge on his right hip that we knew to be his service revolver.

In fact, I remember a jam session a few weeks later when someone else was sitting in on piano — probably Junie Price of Lem’s quartet. The house was pretty full (fuller than we alone usually made it), so the room was warm. Lem had just finished one of his energetic solos and had lathered up a pretty good sweat in the process. When he took off his “plain clothes” jacket his police badge winked gold in the spotlight and the audience gasped in surprise. Most had no idea he was a cop. Without missing a beat, he laid the jacket on the piano top, unstrapped his holster and revolver, and dived back in for another chorus. The applause was at least fifty percent louder than before.

It often took me a couple hours to come down after a gig, so it was pointless to try to sleep. Often I borrowed John’s car, a well-worn brown Kaiser, and tracked Lem down where he was walking his midnight-to-dawn beat in one of the poorer sections of Wilmington. Lem did not seem to mind having a scrawny not-quite-19-year-old white kid tagging along in that all-black neighborhood, although occasionally he had me wait at a distance while he handled a difficult situation. Most of the time we just walked and talked, with him providing stories and advice from his perspective as a black man ten years older. It was a wonderful education for me.

Clifford Brown had been Lem’s friend before he was killed in an auto accident just a year earlier. Lem told me that another member of Brown’s band, Sonny Rollins, usually rode in that car, but for some reason Brown and Rollins had switched places that night. In Lem’s opinion, Brown’s death was much the greater loss. Lem also felt certain that, had he lived, Clifford Brown eventually would have eclipsed Miles Davis — although he didn’t render a judgment, at least not to me, about whether the music world would have been better off had that happened.

Somebody one day contacted John Chowning about having the Collegiates play for a family picnic on a Sunday afternoon around the Fourth of July. John asked Lem to join us on the gig, and Lem accepted enthusiastically. He would also be bringing some “corn.” When we got to the park there was not one picnic but many. The directions provided us were vague, and we couldn’t find the party we’d been asked to play for. Eventually, after perhaps not the most vigorous searching, we gave up.

Lem just shrugged, mentioned that he had played lots of “gigless gigs” (his term), and suggested that since we had the equipment we might as well go somewhere to jam. So we wound up at Dave Arnold’s parents’ house, where Lem broke out the “corn” — two quarts of moonshine he had gotten from a friend.

We expressed some doubts about drinking booze of dubious quality and perhaps dubious origin, but Lem assured us it was good stuff — “because it came in an earthen crock, not a bottle.” So we mixed it half-and-half with cold lemonade, and it went down very smooth. We had a wonderful and very loud afternoon playing and drinking the “corn.”

After that Lem would occasionally drop by John’s house in the afternoon to practice with us and teach us tunes — like “Jordu” and “Daahoud” — and some of the finer points of jazz. Sometimes while we were getting ready he would put on one of John’s Modern Jazz Quartet LPs and play along with it. If I was not watching him, I could hardly tell what was coming from Milt Jackson on the LP and what was coming from Lem. He was that smooth.

Lem told me he had come to use softer mallets, like Bags, because he preferred Jackson’s smoother sound to Lionel Hampton’s “clank” (Lem’s term). A vibraphone player had to combine the gentle touch of a pianist with the wrists of a drummer, Lem said, and Hampton’s background as the latter overshadowed his lack of experience as the former. Lem also experimented with altering his mallets by cutting about two inches off the “back end” and then putting pencil erasers on the tips to help him grip the shafts.

I do not recall much about our recording session in New York, except that John, Dave, and I went up early to hear some music. All that we could find “live” at that hour was French pianist Bernard Pfeiffer and his trio at The Composer, a supper club on West 52nd Street. When they took a break, John Mehegan — jazz critic, pianist, and teacher extraordinaire — played solo, clicking and tapping his heels in a rather unique and percussive way, a kind of vestigial rhythm section.

After the recording session, Lem had to hurry back to Wilmington to walk his beat, so John, Dave, and I went looking for more music. We found where Stan Getz was playing, and as he was coming off the stand John asked him if he might want to jam with us. While not absolutely rude, Getz was derisive of our naïveté, saying something to the effect that he was doing music to make a living and had little energy left to do more of it for fun when the gig was over. We could not help but note the contrast with Lem.

The following summer (1958) John, Dave, and I landed a job in a posh Philadelphia supper club called “C’est La Vie,” playing for dinner and then at the piano bar until the small hours of the morning. It lasted little more than a month, however, before economic conditions forced the club to close. I do not recall that we had any interaction with Lem at that time. Our hours were long and tiring, and he no doubt was busy preparing for his Newport Jazz Festival debut in early July.

In the summer of 1960 I took time out from a trip to Baltimore, where I was to begin grad school, to stop by Wilmington. I managed to contact Lem, and he suggested that we meet at his uncle’s house because there was a piano there. Lem’s uncle — if that is what he truly was — played bass, so Lem wanted to jam. I do not remember the uncle’s name, but he initially was a bit skeptical of me, being young and white and all that, but Lem reassured him, and we had a great time.

Interestingly, the uncle rather playfully insisted on calling Lem by his original name: Ardell. Ardell Davis. Lem never explained why he had changed over to Lem Winchester.

It was then I learned that Lem either had or was in the process of giving up his police job to take his band on the road. He had bought a used hearse to haul the musicians and their instruments — a fairly common means of transportation in those days. (I never bought one, but pushed one on my younger son, who then went through two more of them by his early twenties. They guzzled gas, but at least you knew they had been quietly driven.

David Arnold, January 25, 2008

In 1953 I was living in Tennessee, where signs on city buses still directed “colored persons” to the rear. I had grown up in Delaware, just north of Wilmington, and had absorbed well the advice, well-grounded or not, to stay clear of certain parts of that city — those areas where our own color was in the minority. The summer of 1957, our summer with Lem, was one of those years when the nation was in the throes of determining whether social tolerance would follow from the strengthening decisions that there must be legal tolerance. It was an exciting, even optimistic time, for of course such was the only way to go. Yet there was no guarantee of peaceful outcome. The commingling had not yet become easy.

It is within that context that I most easily place Lem. I remember his music, of course, but he comes striding with it out of that dark part of Wilmington, that dark part of national history, carrying the bright light of refutation. He was a good man. An unforgettable man.

As George has recalled above, we — who were the John Chowning Collegiates — had thrown open the doors of Marshalls Restaurants for Monday night jam sessions. I recall it being a somewhat desperate move: Mondays were quiet anyway, and I sometimes wondered if a trio on any night had a sound big and varied enough to carry the room. But the jam nights worked; musicians from across the city came to play.

Lem Winchester at Marshalls Restaurant, Wilmington, Delaware

photo © David Arnold

One night John, who seemed to have his ear close to Wilmington’s musical ground, said he had heard that Lem Winchester and his quartet might be showing up. I am not sure we knew exactly who Lem Winchester was — perhaps John did — but even so there was a thrill of anticipation such that might have preceded a legendary sports figure come to play with the amateurs. We were eager but anxious. At least I was; in fact I wondered if he would be running us out of a job.

And so Lem did show up one night, with his own quartet. It took a while to set up his vibes; I think we had to move some tables. To me it felt like a major stage redesign that might never come back to the original. A black (then “Negro”) policeman, Lem was. George recalls him with a plain-clothes jacket over his police uniform, but I keep seeing that gold badge winking. And his service revolver.

What was unmistakable was the impression that here was an honestly likable fellow. He might have been the king of Wilmington music, but he was nothing but modest. He smiled; he seemed easy about everything.

The Collegiates, a musically literate trio learning new things with every performance, played what we hoped was jazz — and very often it was. But with Lem and his group there was no question. Marshalls lit up like fireworks. We were hearing what jazz was all about. He might call his style “down home” (another bit of modesty in a way) but it swung with a rhythmic curl and driving force that threatened the walls of the place. On top of it all was Lem’s intricate cascade of notes, at times more than could possibly come from just two mallets, and at other times simply and quietly a delicate, laid-back, slightly off-the-beat sounding of simple melody played in octaves. Push hard and pull back.

John has described that special Lem-thing: how he would fall into a back-beat side-twitch of his head as he played or sat out for choruses. He also sang sometimes as he soloed — not disruptively like Glenn Gould but reinforcingly and, I thought, joyfully. I remember his laugh too, a ready one: the high whicker of a giggle. He was sparely built, without excess. George, above, mentions the necessity of a vibes player having the wrists of a drummer. I was always impressed with how delicate Lem’s seemed, sticking beyond the cuffs of his police-blue shirt. Where could all that power come from?

Lem was uncommonly gentle and forgiving. And he had that best thing of the best in music: the desire to teach, to pass it on.

It is that last thing I remember most — that and his matter-of-fact and unforced tolerance. Of all the musicians in Marshalls on those nights, I was by far the most unaccomplished. I was not a natural at it. I struggled to learn and remember the progressions, the changes, and how to create an interesting bass line. I struggled to have the confidence to play drivingly loud. I would have been the last chosen for the playground jazz team. Yet Lem took the time to help, to give me some ideas. He might have seen promise. Or he might have been kind.

When Lem sided with the Collegiates on other Monday nights, and eventually for the recording, it was an unguarded sign-up. I thought then it was a generous agreement on his part, and it feels even more so now. But I also understand, now, how he simply loved to play. Possibly he was able to see the benefit of a recording, even though there was no plan to distribute it other than through a small-college bookstore in the middle of Ohio. But certainly we could see his gift to us: the benefit, like a windfall, of being fronted by a genius on the vibes. He was among the very best, had friends among the very best — Clifford Brown for one — and so how did we deserve him? I have never stopped wondering.

The recording tells the story. On Lem’s cuts his playing transforms us into a different group. He lifts and drives, lightens the load, inspires. There is promise for us all. The reading of “Strike Up the Band” is a good example. It was a first-play for the three of us. I panicked when he suggested it, right there in front of those all-hearing microphones. But, thanks to Lem, it works. And we probably should not have quit so soon.

In the end we Collegiates had graduations and careers to think about. But for Lem the recording made all the difference. We were both disappointed and relieved when Leonard Feather’s Newport nod went to Lem and not the rest of us but, as John says, we knew who the star was.

One can wonder what would have happened if that first record had not been made, or had not been listened to. In January of 1961 Lem was on the road, a professional musician, commercial recordings to his credit. But he carried with him a relic of his policeman days: a trick with a revolver in which all bullets but one were removed from their chambers. Gun to his head, bar-sitters watching, he would pull the trigger and the hammer would click as the cylinder rotated to an empty chamber. But that night in Indianapolis he used a different gun. The cylinder rotated in the opposite direction.

John, in Paris, heard the news from his father, who was quick to offer his support to Lem’s widow. I heard it from my father, whom John’s father had called. It is still difficult to think about.

In that summer of 1957, Lem Winchester at first appearance was, as we would have said then, a Negro man, a colored man, a man from a different world who played the vibes. Now, after all these years, the color is long-gone and was pointless in the first place. He is simply Lem — one of life’s bright spots.

Notes

[1] A completely updated discographical entry for this recording is available at Michael Fitzgerald’s Lem Winchester Discography.

[2] For additional reminiscences about Wittenberg College and the John Chowning Collegiates from David Arnold, see “No Sign of Age in Our Shadow.” Wittenberg Magazine Online, 2/3 (Spring 2000). http://www4.wittenberg.edu/administration/university_communications/magazine/volume2/issue3/feature_full.html

Author Information:

John Chowning was born in Salem, NJ in 1934. He studied at Wittenberg University in Ohio, and in Paris with Nadia Boulanger. He received a doctorate in composition from Stanford University in 1966. In 1964, he set up Max Mathews’s Music IV at Stanford University’s AI Lab. In 1967 he discovered FM synthesis, a very simple yet elegant way of creating time-varying spectra. Licensed by Stanford to Yamaha, FM synthesis led to a family of synthesizers (DX7) that became the most successful of all time. Until 1996 he taught at Stanford’s Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA).

After graduating from Wittenberg University in 1960, George Lindamood headed off to Baltimore for graduate study (in mathematics) at Johns Hopkins University. He played about a year with Jimmy Driscoll, both in a trio and in Jimmy’s octet, before getting married and dropping out of professional music for the next 33 years. Nearing retirement from a career in information technology, he resumed playing piano and trumpet in groups of two to twenty musicians in and around Sequim, WA, in 1995. Since 2009, he has limited his former jazz work to occasional substituting and has concentrated on church music, both traditional and contemporary/jazz/gospel.

David Arnold earned his bachelor’s degree in 1959 from Wittenberg University, where his grandparents had been on the faculty. Following an initial interest in teaching and education, he found his true passion in photography. He worked as a staff photographer at The New Era newspaper in Deep River, Connecticut, documenting small-town life in the early 1960s and spent a year photographing college life at Colgate University for his book, Heydays. He then went on to serve as photo editor at Time-Life Books in New York before establishing a noted career as an illustrations editor at National Geographic from 1967 to 1994. He traveled the world making pictures and working alongside photographers as an insightful and encouraging editor and his work as illustrations editor was honored by the University of Missouri’s “Pictures of the Year” awards in 1975, 1994, and 1995. Following his retirement, he became an avid researcher into his own family’s history and music continued to be a part of his life.

Abstract:

The three members of the John Chowning Collegiates each recall the time they spent in 1957 in Wilmington, Delaware with vibraphonist Lem Winchester as well as the recording they made together in New York City that led to Winchester’s tragically brief career as a national recording artist and performer.

Keywords:

Lem Winchester, John Chowning Collegiates, John Chowning, George Lindamood, David Arnold, Leonard Feather, Wilmington, Wittenberg College, jazz

How to cite this article:

- Chicago 15th ed.: Chowning, John, George Lindamood, David Arnold. “Remembering Lem Winchester.” Current Research in Jazz 2, (2010).

- MLA 7th ed.: Chowning, John, George Lindamood, David Arnold. “Remembering Lem Winchester.” Current Research in Jazz 2 (2010). Web. [date of access]

- APA 6th ed.: Chowning, J., G. Lindamood, D. Arnold. (2010). Remembering Lem Winchester. Current Research in Jazz, 2 Retrieved from http://www.crj-online.org/

For further information, please contact: