Dennis Sandole’s Unique Jazz Pedagogy

Thomas Scott McGill

“Dennis was an intellectual. Dennis had something special going.” — Benny Golson [1]

Introduction

This article will investigate the jazz pedagogical literature of Dennis Sandole, a legendary Philadelphia-based teacher, theorist, performer, and composer who is perhaps best known for having been John Coltrane’s theory and improvisation teacher and mentor. [2] He was also known for his virtuosity on the guitar and for having developed a conceptually advanced and technically demanding teaching literature that was strongly influenced by twentieth century classical compositional practice. Described as “an incomparable teacher of improvisation,” [3] Sandole encouraged his students to apply a range of highly sophisticated melodic and harmonic techniques such as exotic scales, chord progressions, and substitutions based on interval cycles, polytonality, and synthetic multi-octave scales to the jazz idiom in a unique and personal way, always striving to develop a student’s individual playing style and musical concept. [4] This article will examine Sandole’s performance and teaching career, his pedagogical approach and musical literature, and will consider the influence that his teachings exerted on John Coltrane’s musical output.

Biography

Dennis Sandole was born on September 29, 1913 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and died there on September 30, 2000. [5] He was self-taught and began playing the guitar sometime in his late teens. He progressed quickly on to piano, theory, composition, and arranging, eventually playing in a group with his brother Adolph, a saxophonist. [6] Both Sandole brothers would go on to become jazz musicians and teachers, and would collaborate musically on and off throughout their lives.

Sandole’s performance career began in Atlantic City, New Jersey where he played in the city’s numerous nightclubs before moving to the west coast. [7] He relocated to Hollywood California in the late 1930s, becoming a staff guitarist/composer/arranger for MGM Studios. It was there that he began working with artists such as Billie Holliday and Frank Sinatra [8] and also played and recorded with bandleaders such as Ray McKinley, Tommy Dorsey, Boyd Raeburn, and Charlie Barnet. [9] Around this time, he also became interested in teaching and began work on pedagogical literature for jazz musicians and composers using his experience and close interaction with orchestral musicians to help shape his ability to eventually teach musical concepts to all types of instrumentalists. [10]

He returned to Philadelphia in the mid 1940s [11] to devote the rest of his life to teaching, performing and recording only sporadically thereafter and it was here that John Coltrane became one of his weekly private students at The Granoff Studios, a school that provided training in both jazz and classical music, from 1946 until the early 1950s and both men “remained close.” [12] Word spread about Sandole’s abilities as a teacher and he was sought after for private lessons by many well-respected jazz musicians in Philadelphia, New York, and elsewhere. His skills as a performer, composer, and teacher were held in high regard by many influential modern jazz artists such as Stan Kenton, Sonny Stitt, and Charlie Parker, who reputedly asked Sandole for a lesson. [13] He also completed two pedagogical texts during his career which were reportedly finished by the time he returned to Philadelphia from the west coast. [14] These were the influential guitar method book Guitar Lore, first published in 1976, and Scale Lore, an unpublished text consisting of some of Sandole’s techniques for constructing unique scales as well as material dealing with scalar and harmonic substitution in jazz composition and improvisation.

Sandole’s recorded output is relatively small and includes a collaboration with his brother Adolph of original compositions for jazz ensemble titled The Brothers Sandole: Modern Music from Philadelphia, featuring musicians such as Art Farmer, Teo Macero, and Milt Hinton [15] and The Dennis Sandole Project: A Sandole Trilogy, a collection of material featuring Sandole on guitar in a quartet setting from the 1950s, some solo piano and jazz combo compositions, and excerpts from what he termed his “jazz ballet opera” Evenin’ Is Cryin’. [16] Of particular note as a sideman is his guitar performance on his original composition “Dark Bayou”, recorded by Charlie Barnet. [17] Other examples of Sandole as a composer include “Wayward Plaint” on James Moody’s Running The Gamut [18] and “Hyacinth” on Art Farmer’s The Many Faces of Art Farmer. [19]

Among the best known of Sandole’s large roster of students include saxophonists John Coltrane, James Moody, Benny Golson, Michael Pedicin, Jr., Danny Turner, Bobby Zankel, Billy Root, and Rob Brown; trumpeters Art Farmer and Randy Brecker; pianists Ron Thomas, Matthew Shipp, and Sumi Tonooka; jazz bagpiper Rufus Harley; bassists Craig Thomas and Fred Weiss; and guitarists Jim Hall, Harry Leahey, Billy Bean, John Collins, Dale Bruning, Joe Diorio, Tom Giacabetti, and Pat Martino. [20]

Teaching Outline

Sandole’s lesson plan or “improvisation outline,” as he termed it, consisted of a four-week cycle in which specific topics were covered per week in a prescribed manner. This lesson plan covered the main aspects of a jazz musician’s technical and creative training including technique, ear training, composition, arranging, and concepts for improvisation.

The main feature of Sandole’s lesson material were four- or five-measure etudes he termed “compositional devices” which were composed by Sandole for the student during the lesson and were based on a specific harmonic or melodic topic or concept. Each was written specifically for the student, and they differed significantly from person to person with no two lessons on the same topic being identical. [21] These etudes were designed to extend the student’s technical facility, compositional concept, and aural recognition of advanced harmonic and melodic material. [22]

Creativity and individuality were stressed and Sandole rarely performed on any instrument at lessons to minimize direct visual and aural stylistic influence over his students. This is also perhaps a reflection of the profile of student who sought Sandole’s instruction. “Those studying with him already knew the mechanics and were seeking his insights on matters of concept, his knowledge of exotic scales, and other techniques to broaden an improviser’s range of expression. Sandole was known for his progressive approach to jazz harmony.” [23] He also did not advocate a specific style or “school” of jazz through his teaching [24] and encouraged students to apply the lesson material in any way they deemed appropriate. Pat Martino remarked that, “He taught by not interfering with the blessings each student was given, by amplifying them in any way he could,” [25] and Joe Federico, Sandole’s longtime friend and student, added, “The students that he produced showed that he had a great literature to teach which was expressed differently by each student.” [26] As a consequence, there was no uniform sound or style that could be evidenced amongst his students.

As a general mode of practice, Sandole had non-guitar students perform each compositional device in every key while guitar students were asked to play each device starting on every string and every finger using the original untransposed device only, making octave adjustments where necessary. These procedures were not always rigidly followed and Sandole would encourage students to construct their own methods for practicing the lesson material when he felt it was appropriate and beneficial, for instance a guitarist playing the devices in a I–IV–V modulatory pattern similar to a blues. [27] Students of monophonic instruments typically played the chord voicing portions of the lessons on piano and Sandole asked that his students construct examples that voiced the melody of their harmonization assignments in every voice of the chord, not just in the top voice as is most common in jazz.

Sandole was also known to have possessed a thorough and intimate knowledge of traditional classical pedagogical texts for various instruments such as Franz Simandl’s New Method for String Bass, [28] Niccolo Paganini’s Twenty-four Caprices for Solo Violin for violinists and guitarists, and J. S. Bach’s Two- and Three-Part Inventions for pianists and guitarists, [29] and assigned his students novel and creative ways of studying them. Pianist Matthew Shipp recalls that Sandole “had me take violin books and write bass lines in the left hand and then learn these pieces in twelve keys” in addition to using material from solfege books as improvisational devices over chord changes. [30] Jazz bagpiper Rufus Harley credited Sandole with helping him discover how to play chromatic tones on his instrument and encouraging him to try bagpipes as his primary instrument. [31] Sandole was also knowledgeable regarding many influential theoretical texts such as Vincent Persichetti’s Twentieth Century Harmony, Hermann von Helmholtz’s On the Sensations of Tone, [32] Walter Piston’s Orchestration, [33] and he even possessed cantus firmi with a lineage going back to Antonio Salieri for studies in traditional species counterpoint. [34]

Some General Topics of Study-Compositional Devices

The topics for each lesson included (but were not limited to) subjects such as compositional device on bass line, substitution of note and alteration of note, modes, development of augmented and diminished triads, substitute chords, bitonal and synthetic scales, polychords, alternate triads, deceptive resolutions, two augmented or diminished scales simultaneously, harmonization of exotic scales, Neapolitan on each chromatic note, doubly chromatic chords and scales, and the first, second, and third four bars of blues. [35] Sandole typically started all pupils with the first three from this list, and once an area was completed to his satisfaction, he would ask the student to choose the next topic so that each student went through each topic in a different sequence depending on their area of interest and level of development.

The lesson plans consisted of four designated weeks labeled A, B, C, and D with each week being broken down into three subsections (A1, A2, A3; B1, B2, B3, etc.). A different compositional device was written for A1, B1, and C1. For the final week (D), the student would combine and apply the concepts from the previous three weeks into a final performance project. Following this, the cycle restarted with A week consisting of entirely new material.

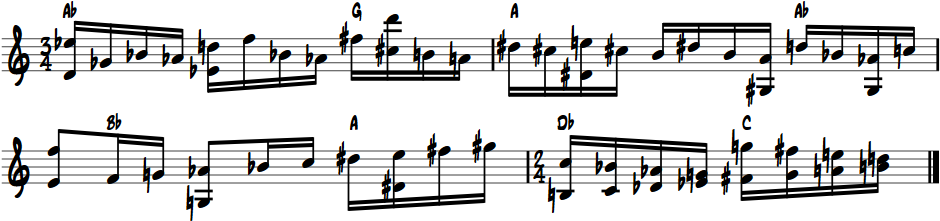

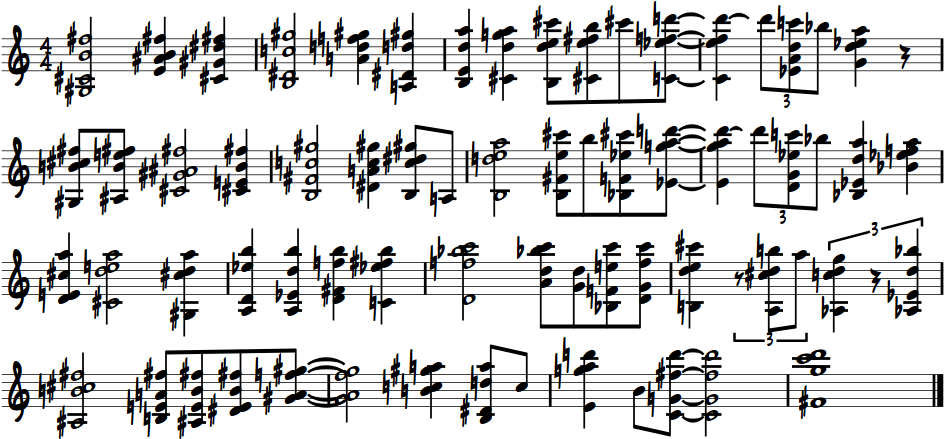

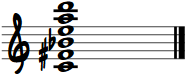

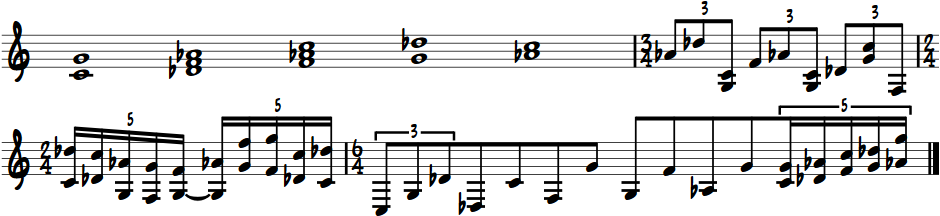

Ex. 1: Sandole: Improvisation Outline [36]

| A Week | B Week |

|

|

| C Week | D Week |

|

|

Description and Analysis of Sandole’s Four-Week Improvisation Outline [37]

A Week

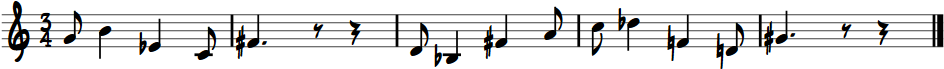

The Sandole outline begins with A Week. The A1 topic for this particular cycle was titled “Neapolitan on each chromatic note,” and the compositional device assigned is quoted below:

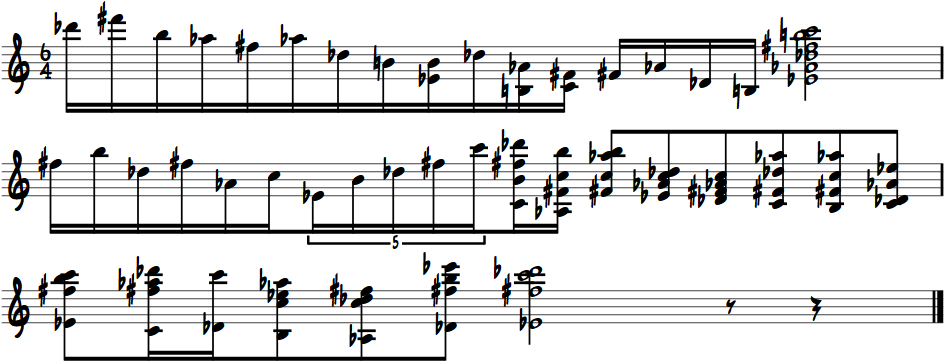

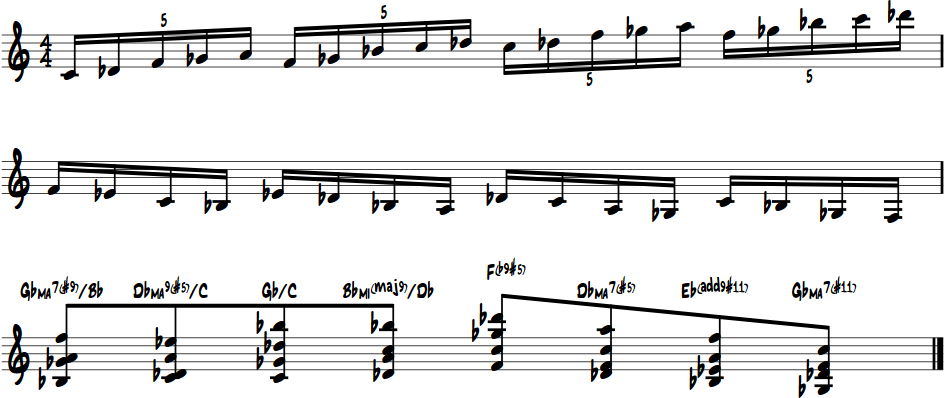

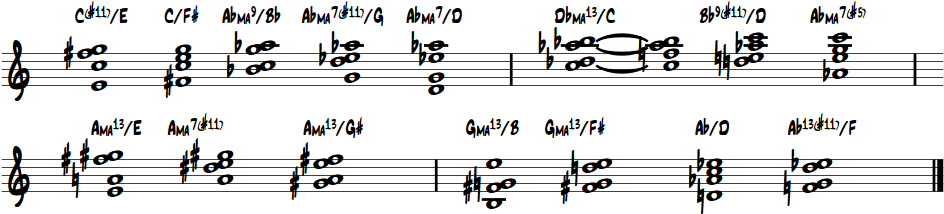

Example 2. Sandole: Neapolitan on Chromatic Scale Tones [38]

This topic deals with descending semitonal resolutions or Neapolitan relationships. The overall harmonic scheme of this device starts on the dominant chord (G) with the chord cycle ascending by semitone with each chord being preceded by its Neapolitan chord. Progressing into the last bar, the chordal root movement leaps by a third with the final resolution being to the tonic chord C. These chords are all major with seventh designations changing between dominant and major seventh sounds depending on the melodic content implied by the compositional device. Guitarists would be required to play this example with what Sandole termed “every string, every finger.” This means that one would be required to play this entire device from memory beginning on every D♮ on the fretboard (the first and lowest tone of this particular device) starting on each of the four fingers on the fretting hand making octave adjustments where necessary. Other instrumentalists and vocalists would be required to perform their devices in all twelve keys.

In this example the double stops in the first three measures consisting of major sevenths and minor ninths are placed on each possible position within a group of four sixteenth notes to accent a variety of rhythmic groupings from twos through to fives. Sandole would, in some instances, highlight the notes he wanted accented within a device to underscore a specific rhythmic scheme he deemed important to the execution and interpretation of the music.

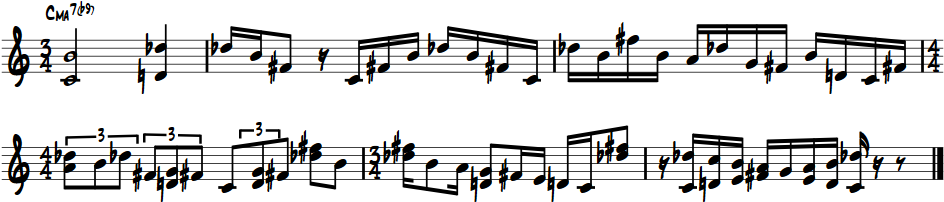

Sandole encouraged students to “paraphrase” or compose an original etude on each compositional device in whatever manner they wished in order to further develop their improvisational and compositional vocabulary as well as to aid in aural recognition of the lesson material and to extend instrumental technique. The following is an excerpt of a composition on the A1 device where the melodic material from the A♭ and G chordal sections has been gathered up and re-ordered as a scale for melodic composition and improvisation vocabulary:

Example 3. Compositional Paraphrase on A1 device [39]

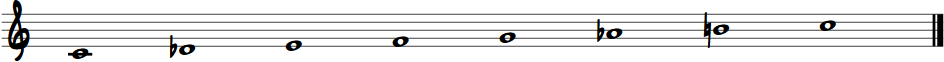

The A2 section consisted of an arpeggio based on a particular scale type, usually an exotic or synthetic scale. For this lesson it was the Raga Todi scale in its first inversion.

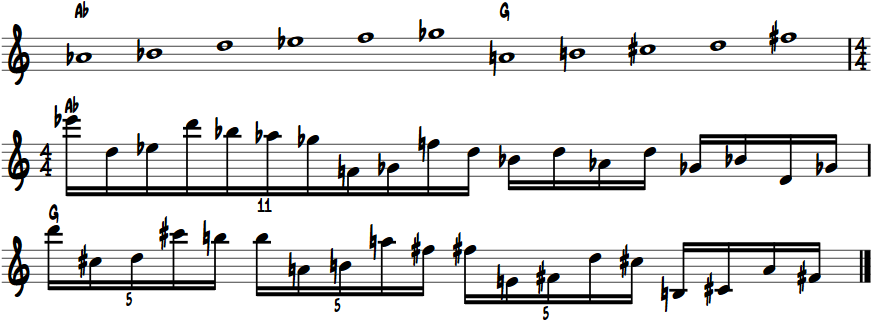

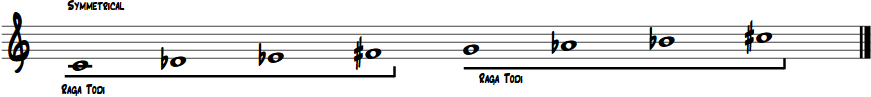

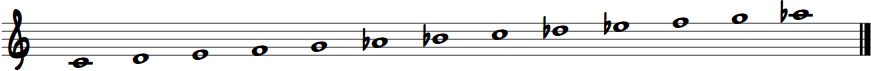

Example 4. Raga Todi Scale [40]

Example 5. Raga Todi Arpeggo — first inversion [41]

The arpeggio was to be played using the “every string, every finger” format for guitarists, and in all keys for other instrumentalists. A composition based on the A2 lesson is quoted below which also makes use of the harmonies contained within the arpeggio formation:

Example 6. Compositional Paraphrase on A2 [42]

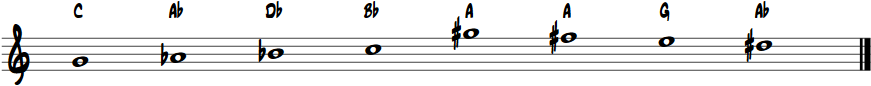

The third aspect of the A lesson was a chord voicing assignment. Sandole wrote a lead sheet type summation or reduction of the A1 device for the student to harmonize as a melody and chords arrangement.

Example 7. Melody and Chords based on A1 [43]

The melody was to be placed in all voices of the chord and not just in the soprano or top voice. This was to be performed on the piano or the guitar according to the student’s preference. Example 8 is a realized harmonization based on four-part chords formed on the first, third, fifth, and sixth strings of the guitar or what Sandole termed a “chord family” or a specific combination of four strings on the guitar. [44] The first musical line in Example 8 has the melody on the first string or top voice, the second line the third string, etc. During the performance of this portion of the lesson, Sandole asked to hear the melody voice a bit more prominently than the others and stressed the importance of musicians being able to put the melody of any tune in any voice of their chord-melody arrangements or compositions. It was typical for a guitar student to perform chordal harmonisations on more than one chord family throughout the four-week lesson cycle although only one is shown here, and Sandole encouraged guitar students to investigate chordal playing using all the possible permutations of string groupings.

Example 8. A3 Chord Study with the melody in every voice using the 1356 string family [45]

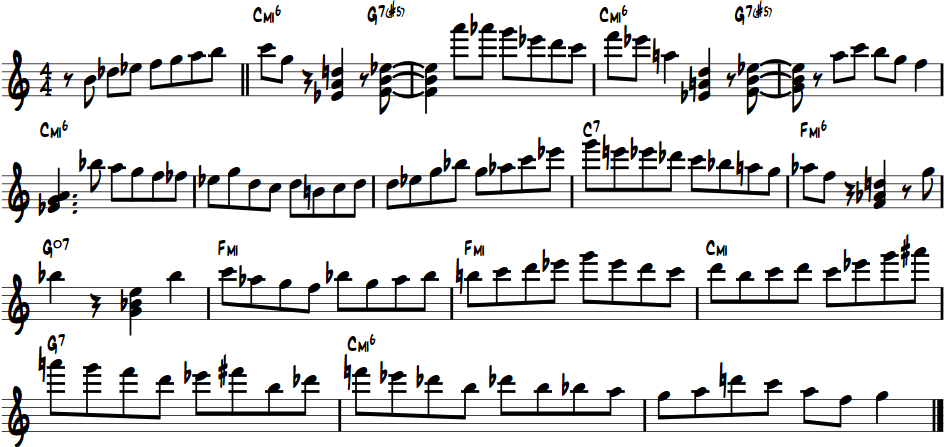

B Week

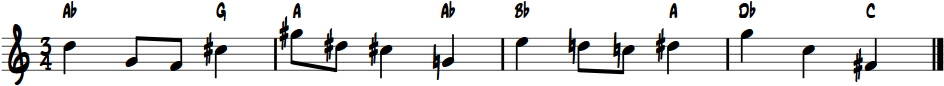

The B week lesson began with a compositional device on another topic, in this case “Alternate Triads,” a coupling of two distinct triads, the first of which began on the tonic C, made into a scale and harmonized. This particular lesson cycle featured a Cmin-5 or diminished triad combined with an Fmaj-6 or augmented triad. Fourths and minor ninths form most of the double stops, and in the last bar there is mirror image reflective writing, which is common in Sandole’s lesson material:

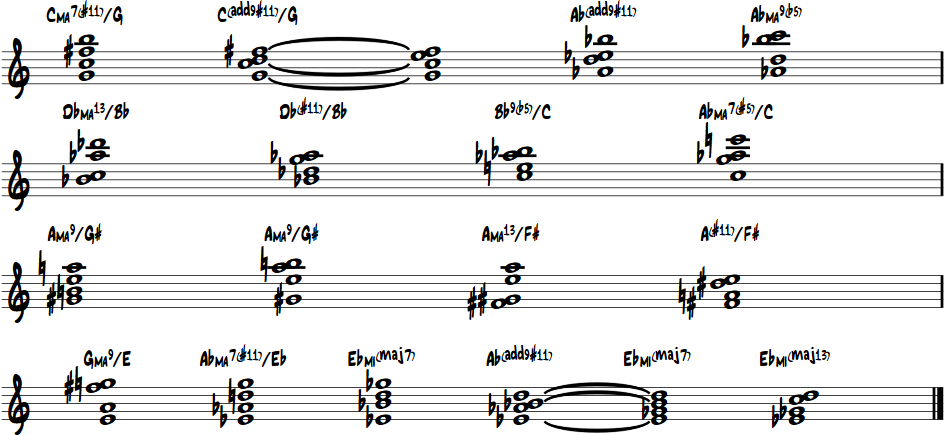

Example 9. Sandole: Alternate Triads [46]

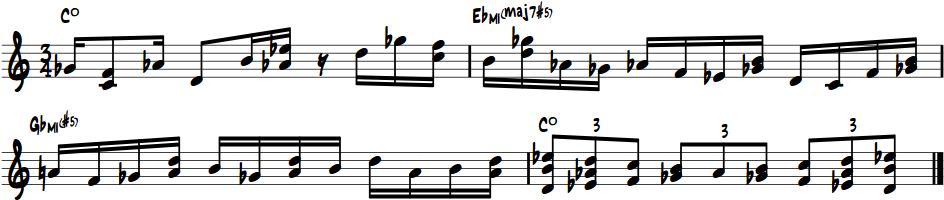

The B1 would be performed at the lesson in the same manner as an A1 lesson using either all keys or “every string, every finger” for guitarists. Sandole encouraged the student to learn the B1 scale in all keys and to write a composition or paraphrase based on it. Example 10 is a compositional excerpt on B1 featuring mostly sequential melodic material:

Example 10. Compositional Paraphrase on B1 [47]

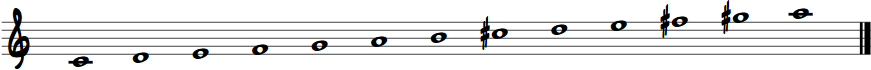

The second task in B Week was an intervallic ear training exercise based on singing a particular exotic or synthetic scale chosen by Sandole. The scale was to be sung using one particular interval per four-week lesson cycle (in this case a Persian or Double Harmonic Scale — C, D♭, E, F, G, A♭, B, C to be sung in ninths) using moveable Do, fixed Do, and a neutral syllable such as “La.” Sandole would typically only want to hear the student sing this exercise in one or two keys at the lesson, but he expected that all keys were practiced during the week. One particular scale was used for intervallic singing until the interval of a tenth was reached and then a new scale was assigned beginning with the interval of a third.

Example 11a. Sandole: Persian Scale [48]

Example 11b. Sandole: Ear Training — Persian Scale in 9ths [49]

The B3 assignment was novel in that it involved using the previous A Week lesson material in a multi-faceted way to create new lesson material. Sandole asked the student to choose eight or nine consecutive tones from the A1 device either moving forwards or in retrograde in which any tone could be altered using a sharp, flat, or natural if so desired. This collection would then be used as the pitch material for a new melody to be harmonized by the student using the A1 chords placed in any order. For this particular lesson, eight consecutive unaltered tones were taken from the top line of A1’s (Example 2’s) fourth measure, beat 1 beginning on G♮ then progressing in retrograde into beat three of the third measure ending on D♯. This harmonization uses the A1 chords in a new order.

Example 12. Harmonization of A1 Melodic and Harmonic Material [50]

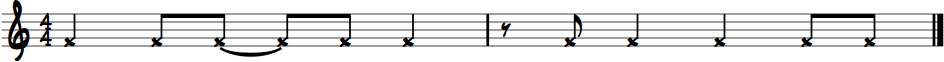

This new melody and chords would then be applied to a two-bar “Rhythm Study” which Sandole would have the student copy from his personal manuscripts at the lesson. These rhythm studies were usually based on rhythmic patterns of other cultures and musical traditions. The rhythmic pattern could be notated and performed strictly, or could be improvised by the student when performing the B3 melody and chords assignment at the lesson.

Example 13. Sandole: Rhythm Study applied to A1 harmonization: “Danza” (Puerto Rico) [51]

The melody would then be placed in each voice of the chords for performance as per the A3 procedure. Example 13 is an excerpt demonstrating the melody on the top and bottom voices using four-part chords on the second, third, fourth, and fifth strings of the guitar.

Example 14a. B3: Harmonization on 2345 String Sets — melody in top voice [52]

Example 14b. B3: Harmonization on 2345 String Sets — melody in bottom voice [53]

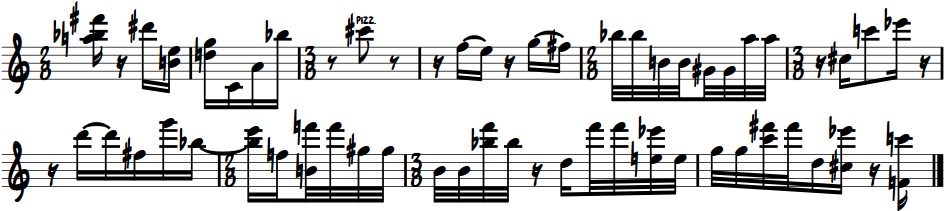

C Week

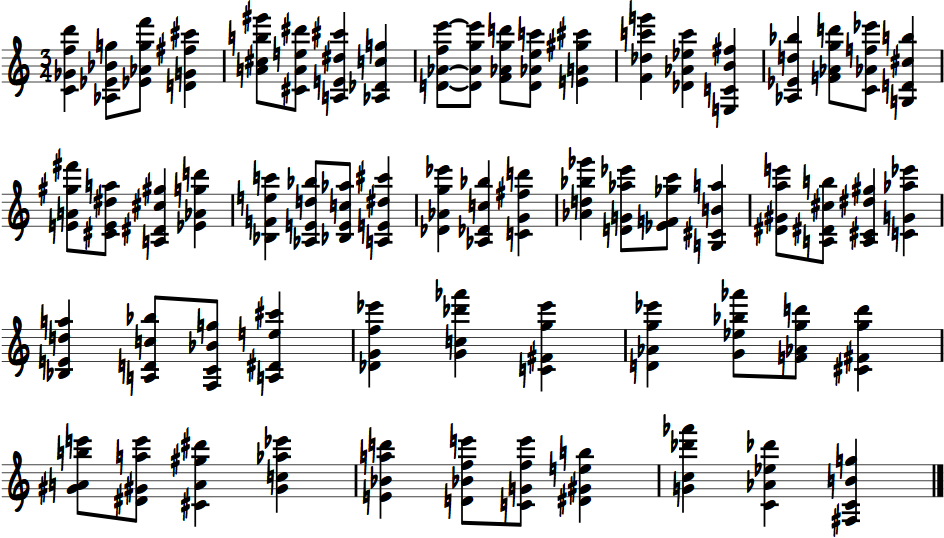

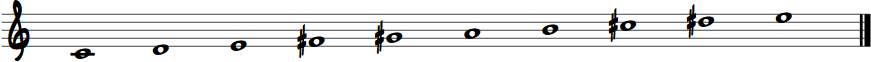

The beginning of C Week consisted of a third category of compositional device, in this case “Bitonal Scales” which consisted of a scale implying two different tonalities that, in many cases, was a two octave scale where the octave is “missed.” [54] Example 15 is a Bitonal Scales device combining the scalar characteristics of C Major with an augmented fourth, and E Major with an augmented fourth with the octave C being skipped giving the upper range of the scale a more distinct E Major+4 or Lydian sound. The same performance procedures for A1 and B1 applied for C1. Again, fourths and minor ninth double stops predominate within the compositional device and contrary motion is used as a cadential figure:

Example 15. Sandole: C1 Bitonal Scales [55]

As stated previously, daily practice of the scalar material and a paraphrase composition was encouraged. This section of a compositional paraphrase on C1 utilizes double stops and six note harmonies diatonic to the C1 bitonal composite scale.

Example 16. Compositional Paraphrase on C1 [56]

The second part of the C lesson involved sight-singing. Upon commencing their studies, Sandole would assign a student a text for sight-singing based on what he felt was appropriate at that given time. Typically, Sandole preferred The Sight-Singing Manual by Allen McHose and Ruth Tibbs for tonal work and Modus Novus by Lars Edlund for contemporary tonal and atonal work. Although Sandole asked to hear students perform only one line for their sight-singing book at their lesson on C Week, he stressed that each student should practice one line of sight-singing each day. As in the B2 ear training assignment, each sight-singing example was to be performed in moveable and fixed Do, and a neutral syllable, the first tone becoming Do for atonal exercises when using moveable Do. Exercise 16 represents a typical C2 sight-singing assignment to be sung at a lesson.

Example 17. Excerpt from Modus Novus, p. 57 [57]

The last assignment of this week was what Sandole termed “Extended Phrase,” or a transcription of a jazz solo. Typically, John Coltrane’s “Giant Steps” was the first solo he asked to be transcribed for new students, but after this was completed the student would choose the work to be transcribed. Sandole asked for only eight to sixteen bars of a solo to be transcribed for maximum benefit with the transcription to be performed at the lesson from memory at the same tempo as the original recording. The transcription for this particular lesson was the first seventeen bars of McCoy Tyner’s piano solo on “Inception.”

Example 18. Extended Phrase — Transcription: McCoy Tyner solo “Inception” [58]

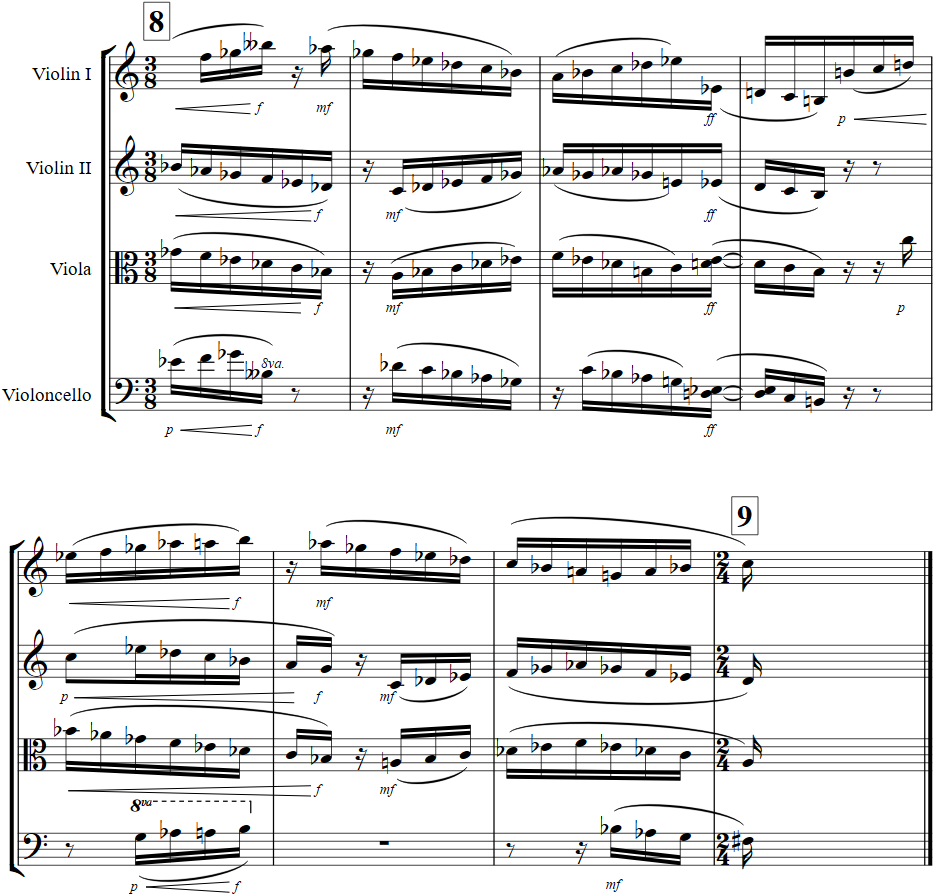

In addition to transcription of jazz material, Sandole advocated the transcription and performance of classical music for students who showed interest in extra-curricular work of this type. Example 18 is an excerpt from a transcription done for C Week of Anton Webern’s String Quartet, Op. 28 arranged for guitar.

Example 19. Transcription Excerpt: Webern String Quartet Op. 28 3rd movement. Bars 13 through 22 [59]

D Week

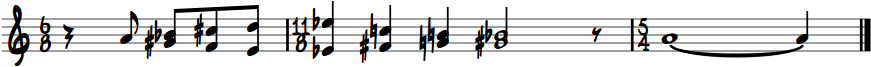

The final week of the lesson cycle was meant to be the creative culmination of the work done in the previous three weeks which would then be applied to a jazz standard of the student’s choosing.

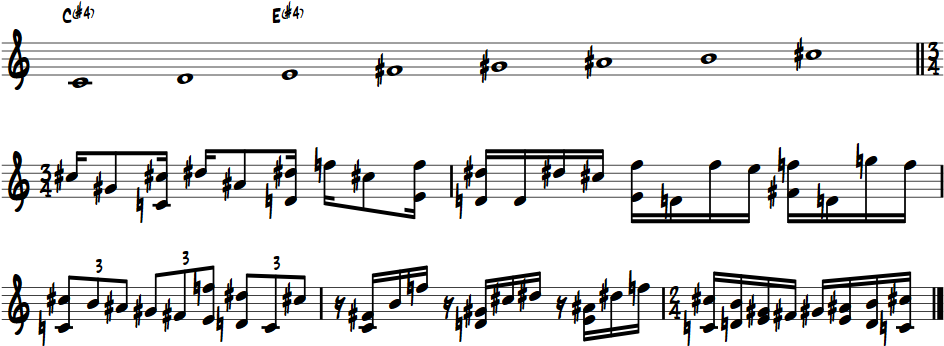

For D1, students were asked to select eight or nine consecutive notes from their A1, B1, and C1 lessons, and to construct a new melody in the same manner as prescribed in the B3 lesson (forward or retrograde in any combination with any note subject to possible alteration). The student would then harmonize this new melody with the chord changes from eight consecutive bars of their chosen jazz standard. Example 19 illustrates the melodic tones chosen from the A1, B1, and C1 lessons (Examples 1, 8, and 14 respectively). The top line in Example 20 is taken from the third measure of A1 beginning on E and ascending until E is reached again, the second line from the first beat of the fifth measure of B1 beginning on A and progressing backwards into the last beat of measure four, and line three was taken from the last two pitches in measure two of C1 progressing into the next measure until the note E is reached.

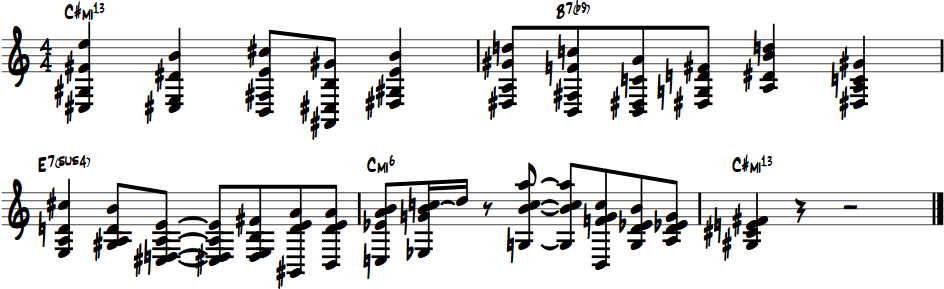

Example 20. Eight consecutive tones from A1, B1, and C1 devices for melody to be harmonized with jazz standard chord changes [60]

The rhythmic values of the melody were chosen by the student and then harmonized using the chords of the chosen jazz standard. The standard tune used for these examples is “Fall” by Wayne Shorter used in its entirety. The original and newly composed melody of the tune was to be placed in any voice or combination of voices the student chose. In these examples, the melody is in the top voice throughout using a variety of four note voicings based on the 1236, 1356, 2345, and 2456 guitar chord family string combinations.

Example 21. D1 Original chords and melody arrangement of Wayne Shorter’s “Fall” [61]

Example 22. D1 Original composition on “Fall” using the 24 consecutive melodic tones in Ex. 20 [62]

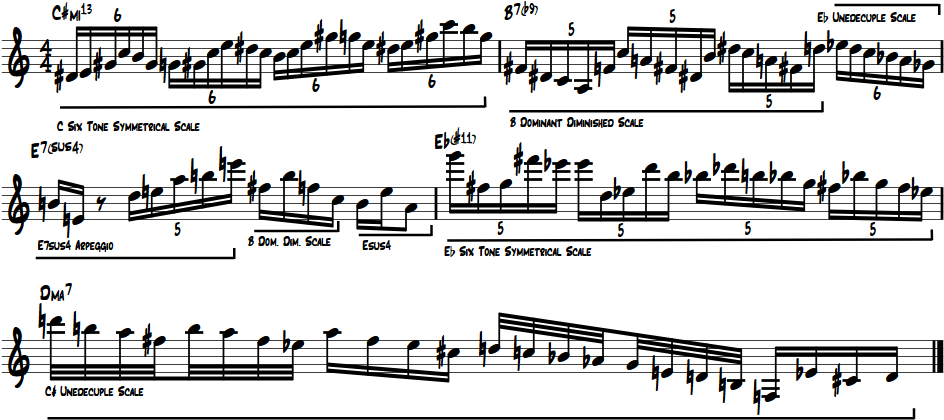

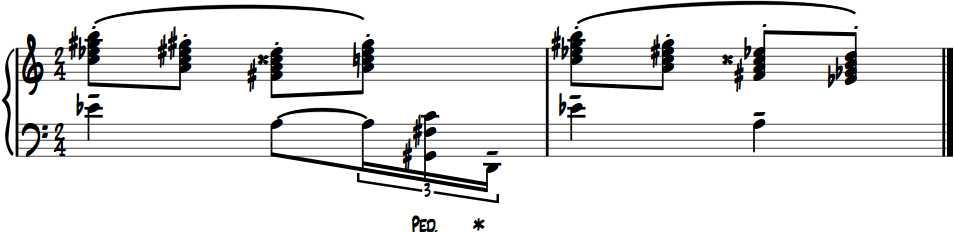

For D2, an accompaniment and solo were to be written based on the tune’s harmonic structure. Example 22 is a four bar excerpt from an accompaniment using similar voicing schemes as the D1 melody and chords version, and Example 23 is an excerpt from the composed solo section using bars 5 to 9 of the tune. The scales employed were the Six Tone Symmetrical Scale or Schoenberg’s “Ode-to-Napoleon” hexachord [63] of alternating augmented seconds and semitones (ex. On C as tonic: C, D♯, E, G, A♭, B, C), the Dominant Diminished Scale of alternating semitones and whole tones (ex. On B as tonic: B, C, D, D♯, E♯, F♯, G♯, A, B), and the D3 scale of this particular lesson week Sandole composed called an “Unedecuple,” consisting of eleven discrete tones to be discussed in the next section.

Example 23. D2 accompaniment [64]

Example 24. D2 solo [65]

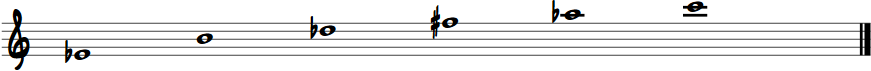

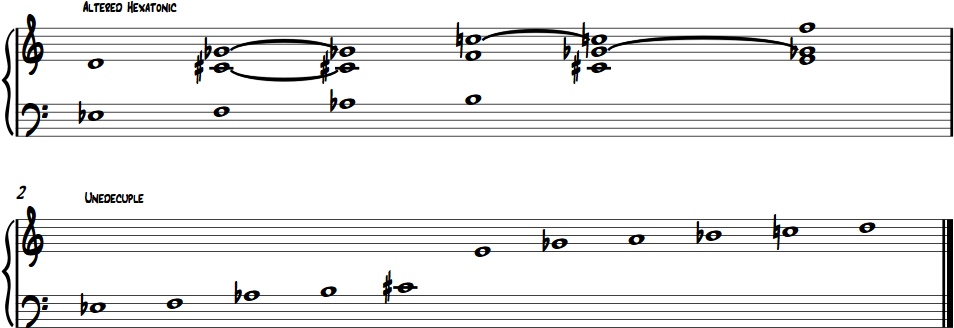

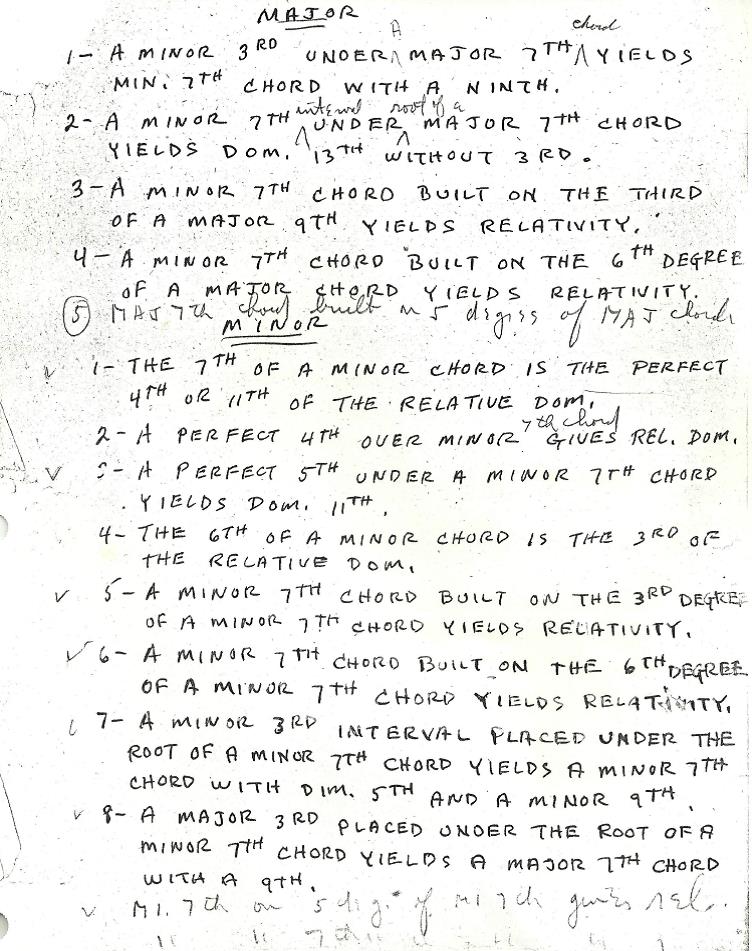

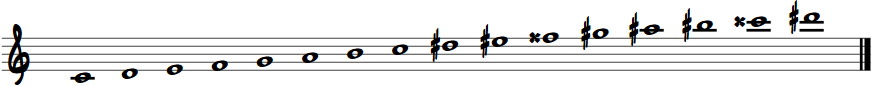

The last section of this lesson, D3, consisted of an original scale composed by Sandole and harmonized for the student to learn on their instrument and compose with in any manner they wished. Sandole stated that the D week scales he composed were based on what he termed “the student’s particular musical response” to the previous A, B, and C lessons and characterized them as “custom made” for each student. [66] Example 24 is a D3 “Unedecuple” or eleven tone scale harmonized as an “Altered Hexatonic” scale. The emphasis is on dissonant intervallic combinations in the harmonization such as augmented fourths, major sevenths, minor ninths, with the final chord consisting entirely of semitone intervallic relationships:

Example 25. D3 Extended scale and harmonization [67]

Example 26 is a compositional excerpt based on both the scalar and harmonic elements of the D3 material. Many of the chordal elements are stated verbatim from the given harmonization, but some are embellished by the free use of individual scalar tones or fragments. D3 would constitute the end of the four-week cycle and the student would begin the cycle again with a new A1 and so forth.

Example 26. D3 Compositional Excerpt [68]

Although Sandole’s lesson curriculum differs greatly from traditional chord/scale-oriented jazz pedagogy’s emphasis on a specific family of scale systems (major, harmonic and melodic minor scales and their modal inversions, pentatonic, whole tone, and diminished scales), memorizing idiomatic lines and licks for use in performance, and its tendency to emphasise and codify the work of the masters of the idiom within these tonal systems, Sandole’s four week outline could be viewed as a logical and evolutionary next step in a jazz musician’s development, encouraging the student to develop his own tonal/scalar systems and substitutions for improvisation, to hear more abstract and modern tonal relationships more easily, and to develop a mature compositional concept unique to oneself.

Analysis of Sandolean Compositional Devices and Their Relationship to Twentieth Century Classical Compositional Practice

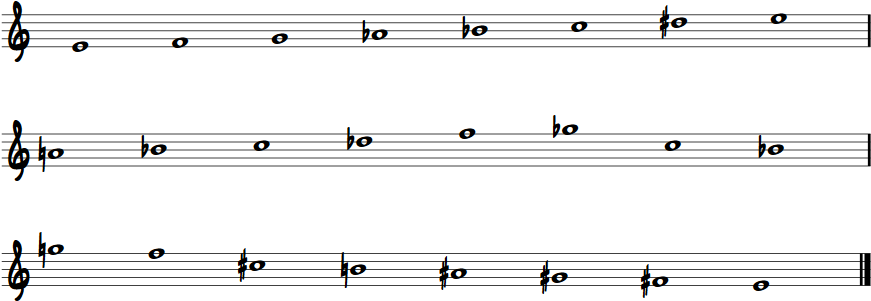

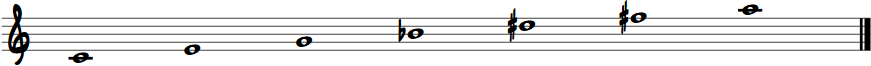

The Use of Tetrachords

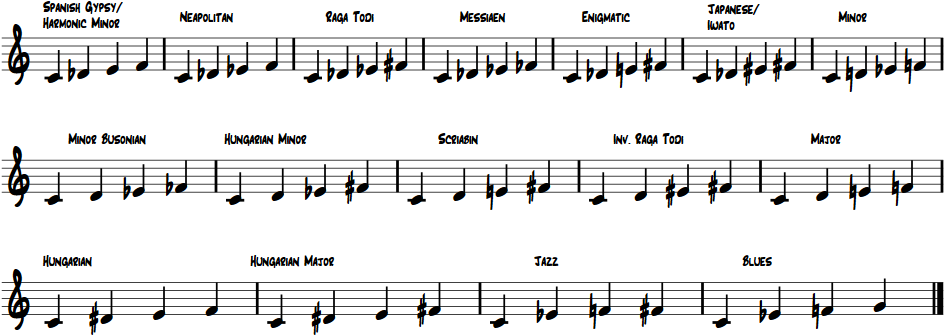

In his compositional practice, Sandole used tetrachords to create unique scales that produced novel and colourful harmonic and melodic effects. This technique is pervasive in his pedagogical methodology. Example 26 taken from his unpublished text Scale Lore is a list of the types that he generally preferred. Their names are noteworthy as they reveal Sandole’s interest in exotic scales and twentieth century composers and composition. These were used both in their pure form, and chromatically altered according to compositional and pedagogical expediency:

Example 27. Sandole: Scale Lore — “Type Tetrachords” [69]

Sandole frequently created and employed original scales in his musical literature that have no octave repetition by joining similar or dissimilar tetrachords, trichords, pentachords, and hexachords and used them as the basis for his lesson material compositional devices. Composer-theorist Vincent Persichetti, an acquaintance of Sandole’s, describes this technique in the following manner:

New scales may be so built with similar or dissimilar tetrachords that the tonic is not repeated at the first octave. When the tonic is missed and the tetrachords are continued, a two octave scale or multi-octave scale may evolve. [70]

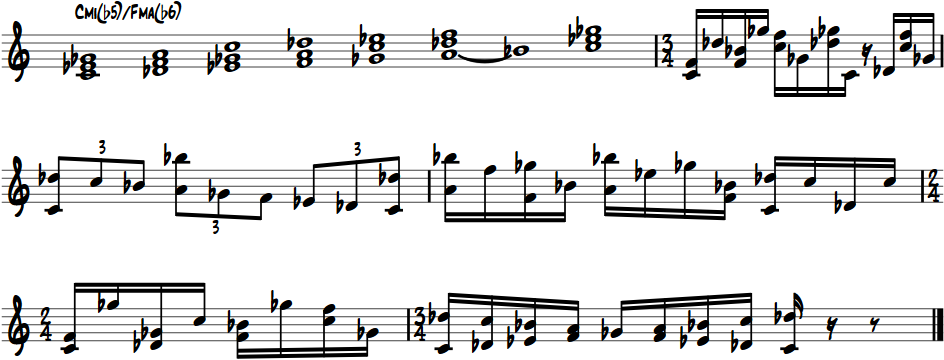

Example 28 is a C1 lesson compositional device based on a Cma7♭9 (lowered ninth) sound:

Example 28. Sandole: Compositonal device on alteration of note [71]

The resultant scale used as a mirror image at the cadence misses the octave (C, D, E, F♯, G, A, B, D♭), the result of joining two Scriabin (Lydian) tetrachords at the fifth degree (G). Sandole’s melodic writing in the first bar outlines two quartal harmonies a semitone apart (F♯, B, D♭, an inversion of D♭, F♯, B, and C, F♯, B) and the registral position of the note D♭ stays fixed in the upper register throughout with a D♮ fixed in the lower to enhance the line’s polytonal effect.

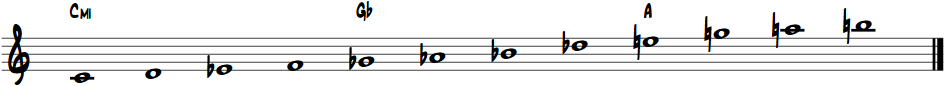

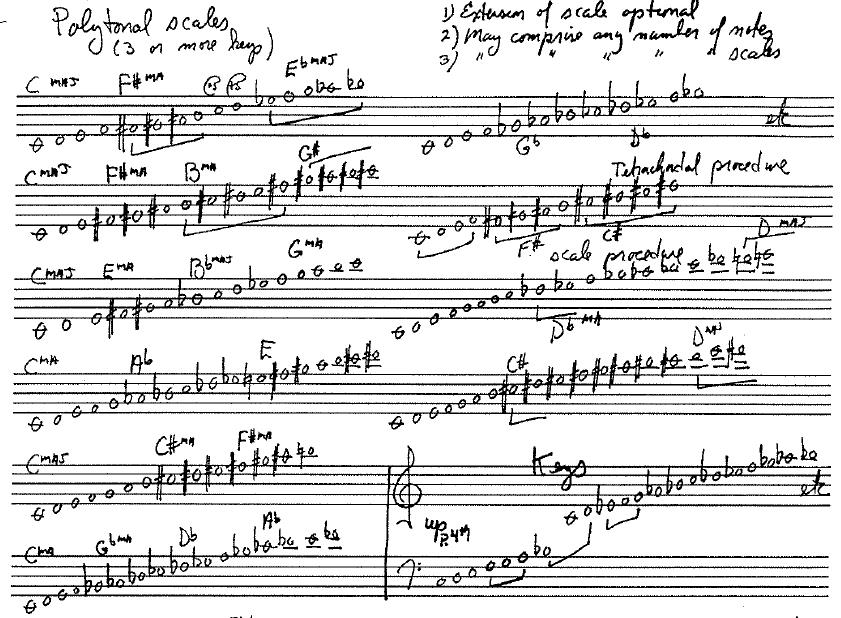

Many of Sandole’s scale structures extend into nine, ten, eleven, and twelve tone scales which he used primarily as modes to write his compositional devices. Sandole’s modal use of these scales is similar to postwar American twelve tone practice as advocated by theoreticians and composers such as Richard S. Hill, Ernst Krenek, and George Perle which, in the main, stressed the interval content of aggregates rather than interval order. [72] A clear illustration is this twelve tone scale or “set” which is the product of three dissimilar tetrachords joined to create a multi-octave polytonal scalar unit.

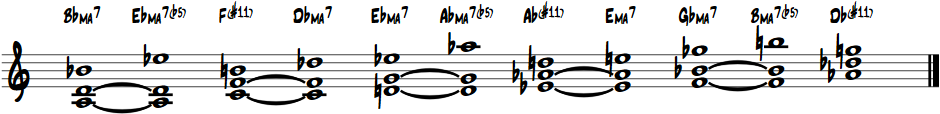

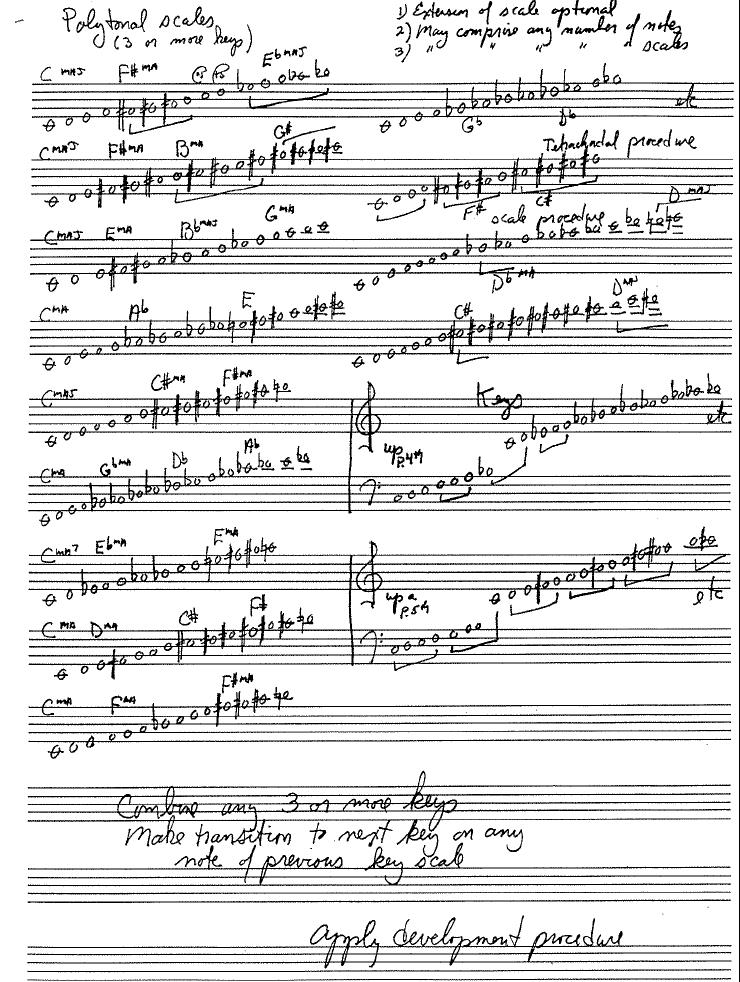

Example 29. Sandole: Polytonal scales [73]

The key areas spelled out by Sandole reflect the joining of a C minor tetrachord (C–D–E♭–F), a R–2–3–5 tetrachord on G♭ (G♭–A♭–B♭–D♭) and an E minor tetrachord (E–G–A–B) implying an A or A9 sound specifically.

Sandole’s tetrachordal scales such as this one give an improviser the ability to imply many different tonal areas for playing “outside,” the ability to access twelve tone “modes” easily by simply placing the first tone after the final one generating eleven discrete scalar inversions, twelve tone arpeggios based on these modes, and the ability to create new scales or sets fairly easily on one’s instrument by simply interchanging or altering the tetrachords themselves. From a compositional standpoint, these scales can allow for twelve tone or pan-chromatic writing that contains tonal/polytonal references and the possibility of secundal scalar passages without necessarily negating serial ordering. Sandole’s tetrachordal procedures provide a straightforward methodology regarding the use of twelve tone modality for both composition and improvisation in contemporary jazz or other types of music.

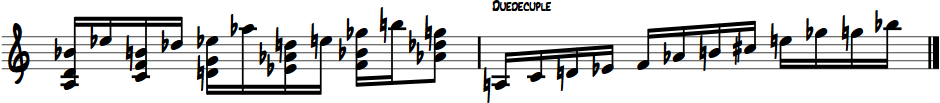

Example 30 illustrates an analysis of a D3 lesson Twelve Tone or “Duedecuple” scale with its accompanying harmonization:

Example 30. D3 Duedecuple scale and harmonization [74]

This scale could be viewed as the joining of similar and dissimilar trichords that include various pentatonic scale fragments (A–C–D, E♭–F–A♭, B–C♯–E), or as the joining of dissimilar tetrachords (jazz: A–C–D–E♭, Raga Todi: D–E♭–F–A♭, pentatonic in inversion: B–C♯–E–F♯, and Hungarian minor: E–G♭/F♯–G–B♭/A♯). The harmonization to the left could be rationalized as a row of alternating partial major seventh type chords in second and third inversion of primarily quartal construction, the implied root movements progressing in major seconds, minor and major thirds, and perfect fourths.

Example 31. D3 Harmonization — harmonic analysis [75]

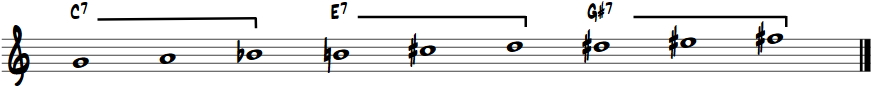

Chord Progressions based on Interval Cycles

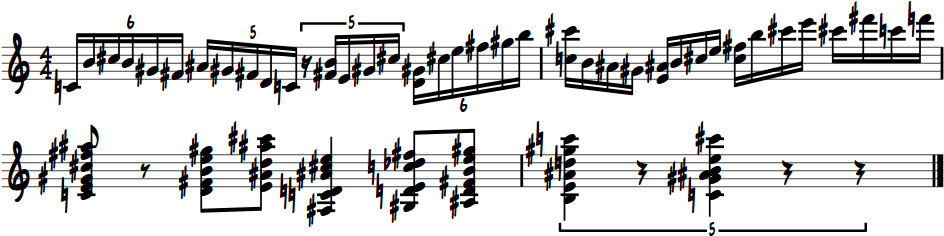

The use of interval cycles of all types to construct harmonic progressions, tetrachordal root movement, and scalar material plays a large part in Sandole’s pedagogical literature. Example 32 taken from an A1 lesson on the topic “Minor Progression” shows a wide variety of intervallic chordal root movements in a relatively small amount of musical space: major thirds, perfect fourths, minor seconds, and major seconds. In measure two, a leading tone root B7 chord is used as a substitute dominant chord for G7 (a major third cycle of dominant seventh substitutes).

Example 32. Sandole: Minor progression [76]

Example 33 is a compositional device on “Substitute Chords” utilizing minor thirds cycles of mima7♯5 type chords as dominant substitutes, and using a diminished chord as tonic:

Example 33. Sandole: Substitute chords [77]

Of particular note is the E♭mima7♯5 chord which is enharmonically a B major triad in its first inversion with a raised ninth or minor third, an unusual chord to see in a lead sheet format and an identical formation to Bela Bartok’s “major/minor chord.” [78] A similar chord appears in the next bar on G♭ if one considers the F♮ in the melodic material. This chord is also of significant importance in the music of Alexander Scriabin as demonstrated here in his Piano Sonata No. 7, Op. 64 (1911–1912), and the modal use of non-dodecaphonic sets for melodic and harmonic material can be observed in both the Scriabin work and Sandole’s Example 33. [79]

Sandole’s inventive use of this specific chord can either be rationalized by its use as a II7 (D7) substitute within a minor thirds cycle noting the B Major Pentatonic Scale fragments in the melodic content (B, A♭, G♭, E♭) as part of an overall C Octatonic Diminished Scale sound, or as a V7 chord (G7) substitute rationalized by the chord’s inclusion in an Augmented Six Tone Symmetrical Scale of alternating minor thirds and minor seconds (G, A♯, B, D, E♭, F♯, G) or Schoenberg’s “Ode-to-Napoleon” hexachord. [80]

In bars 37 and 38 of the Scriabin sonata, we see a similar cycle of minor thirds use of these chords including roots on E♭ and G♭ in the right hand, as in the Sandole example, with an emphasis on augmented fourth bass motion in the left.

Example 34. Scriabin: Sonata No. 7 for Piano Op. 64, mm. 37–38 [81]

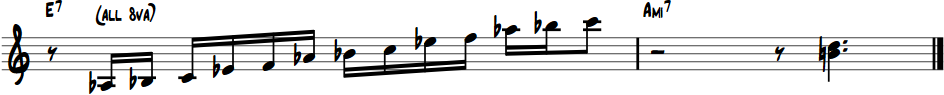

In the Sandole device, the B major portion of the E♭ mima7♯5 chord could be viewed as an appoggiatura chord belonging to a major thirds cycle in place of G resolving to C and is the relative major sound to A♭/G♯ minor, a common G7 substitute sound in jazz. Also, the use of major pentatonic scales (and fragments thereof) based on the third of the V chord is commonly observed in modern jazz improvisation, such as in Chick Corea’s solo on “500 Miles High” on the Return To Forever album Light As A Feather (1972) in which a complete A♭ major pentatonic scale is played over an E7 chord before resolving to Ami7:

Example 35. Glanden: Transcription of Chick Corea solo “500 Miles High”, m. 8 [82]

In conclusion, Example 33 ends with mirror writing in tetrachords. Starting on D, this constitutes a Messiaen tetrachord on D followed by a Hungarian major tetrachord beginning on A♭. Taking C as the tonic, this would be a C minor tetrachord followed by a G♭ Raga Todi (inversion) tetrachord.

Example 36, taken from the A1 topics “First Four Blues” and “Second Four Blues” demonstrate how Sandole combines his tetrachordal melodic procedures and cyclic chordal root movement techniques in a unified way. The tetrachords are labelled using Sandole’s terminology:

Example 36. Sandole: “First Four Blues” and “Second Four Blues” [83]

This skillful use of tetrachords facilitates an improviser’s ability to negotiate difficult changes in a fast harmonic rhythm and Sandole stated that he “suggested tetrachord techniques” to Coltrane during the course of their studies together. [84] Noteworthy is the liberal use of an “all interval four-note chord,” [85] or Enigmatic tetrachord in this example and the employment of the bluesy sounding “Neapolitan altered tetrachord” (D♯–E–F–G♯/A♭), the enharmonic equivalent of the ancient Greek “Chromatic” tetrachord. [86]

Example 37 taken from Scale Lore illustrates Sandole’s technique of joining melodic fragments of various sizes from three to seven notes to create extended polytonal scales based on various intervallic cycles such as minor thirds, major thirds, minor seconds, and perfect and augmented fourths.

Example 37. Sandole: Scale Lore — excerpt from polytonal scales [87]

Use of Contrary Motion

A great many of Sandole’s compositional devices employ contrary motion figurations as evidenced in earlier examples. This device is also common in the work of Bela Bartok.

Example 38. Bartok: Music for Strings, Percussion, and Celeste (1936) [88]

Example 39. Sandole: Alternate Triads [89]

Sandole seems to have held Bartok in high esteem and he enthusiastically recommended the study of his work. [90] He evidently told John Coltrane during the course of his studies, “In Bartok’s string quartets, you can hear an entire symphony orchestra.” [91] Example 40 is an excerpt from the Coda section of Bartok’s Third String Quartet which displays contrary motion prominently between the instruments.

Example 40. Bartok: String Quartet No. 3 Coda section: mm. 53–40 [92]

Example 41 is the same section of music, this time from a guitar arrangement of this work assigned by Sandole:

Example 41. Bartok: String Quartet No. 3 Coda section: mm. 53–40: guitar transcription [93]

In the guitar version on one staff, the contrary motion is more apparent, and its similarity to the type that Sandole employed in his compositional devices is striking. Considering Sandole’s words and the content of his compositional devices, it seems possible that Bartok’s work had a direct influence on his musical and pedagogical output.

Extended Scalar Based Arpeggio Studies

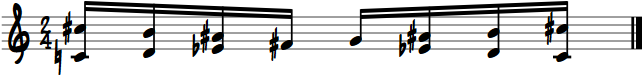

Sandole’s arpeggio assignments were verticalizations of exotic and synthetic scales usually in thirds in a manner similar to that advanced by Alois Hába in his New Theory of Harmony [94] and to what Joseph Schillinger called “Sigma” or “First Expansion,” [95] and he instructed his students to exhaust all modal inversions of these arpeggios before moving to the next type. Below is a typical B2 arpeggio lesson example based on the Hungarian major scale:

Example 42. Sandole: Hungarian major scale arpeggio [96]

This structure yields a C dominant seventh harmony with an augmented ninth, augmented eleventh, and thirteenth as upper extensions which constitutes a truncated C dominant diminished scale with only one note (D♭) missing. In addition to aiding soloists with accessing a wide variety of unusual “upper partial” sounds for a wide variety of harmonies, these arpeggio exercises seemed to be of particular benefit for bassists as it helped them develop the skill of being able to create walking lines over virtually any harmonic structure they might come across in jazz from any position on the fingerboard. [97]

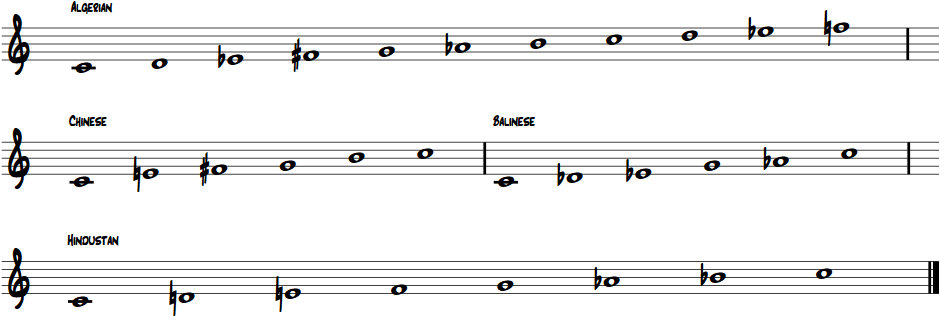

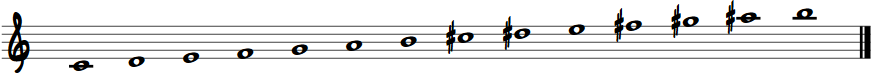

Exotic and symmetrical scales

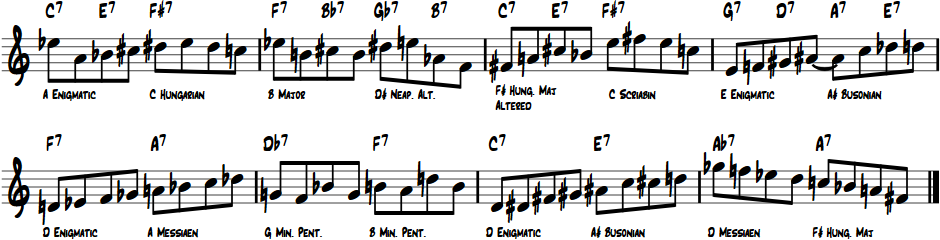

Sandole advocated the use of exotic scales in jazz improvisation and composition as early as the mid 1940s and a number of these scales were contained in the earliest versions of his pedagogical texts Guitar Lore and Scale Lore. [98] A small selection of the exotic scales Sandole utilized in his teaching are listed below:

Example 43. Sandole: Exotic scales [99]

Example 44. Sandole: Exotic/synthetic scales [100]

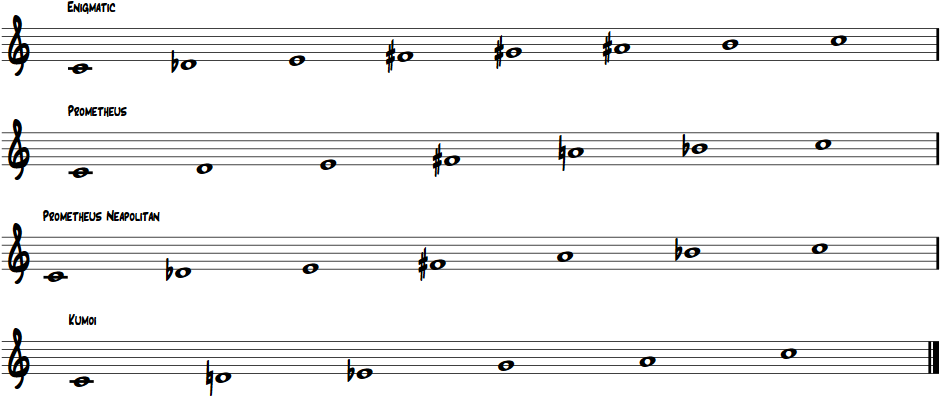

Sandole’s inclusion of the Prometheus scale reveals his interest in Scriabin’s music, as the scale is derived from the so-called “mystic chord,” a predominantly quartal harmonic structure that forms the basic compositional material of his work Prometheus: The Poem of Fire:

Example 45. Scriabin: Mystic chord [101]

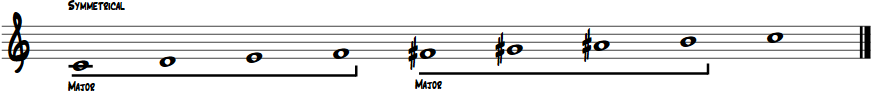

Symmetrical scales are also prominent in Sandole’s pedagogical literature. In the main, these take the form of either the coupling of similar tetrachords to form scales larger than, or within, one octave:

Example 46a. Sandole: Symmetrical Scales [102]

Example 46b. Sandole: Symmetrical Scales [103]

Or, by constructing scales that “melodize” cyclic chord movement, in this case dominant seventh chords in an ascending major thirds cycle:

Example 47. Sandole: Major thirds relationship [104]

The second scale in Example 46 and Example 47 are both identical to Messiaen’s sixth and third Modes of Limited Transposition respectively, [105] and illustrate Sandole’s awareness of Messiaen’s use of symmetry, particularly in constructing scale material that has harmonic as well as melodic implications.

Sandole used exotic scales in their pure and altered forms in virtually all aspects of his four week lesson cycle such as compositional devices, ear training exercises, arpeggios, and compositional work. Example 44 is a B1 compositional device written for piano based on a pure or unaltered Japanese scale complete with harmonization that shows one aspect of his exotic scales writing within the context of composed lesson material:

Example 48. Sandole: Harmonization of exotic scales (Japanese) [106]

Added Intervals

Sandole frequently added combinations of intervals to more basic harmonic formations to create colorful upper extensions and polytonal relationships that are not diatonic in origin. In this device he termed “Doubly Chromatic Chords,” he adds a series of intervals to a basic B♭mi7 chord. If collected as a scale within one octave, this is a ten tone scale on B♭ with only D and A missing, a formation that is similar in concept to Hába’s “10 Note Chords,” [107] and Messiaen’s “Mode 7.” [108] “Doubly Chromatic,” in Sandolean terms, is the presence of three chromatic tones within an overall scale system whereby at least one of the tones is placed in a different register so that the tones are not consecutive semitones. These relationships can overlap and are not restricted to only three tones within one scalar system.

For instance, the tones B♭, B, and C in the scale system of Example 49 illustrate this concept clearly, as well as B, C, and D♭, etc. Sandole’s distribution of doubly chromatic interval relationships over a three octave range produces obvious polytonal references such as the last four notes which comprise a Cma7 chord.

Example 49. Sandole: Doubly chromatic chords [109]

These sorts of pitch relationships are common in twentieth century classical music and Sandole’s use of these abstract types of melodic and harmonic figurations in his improvisational outline as observed in Example 52 is quite unusual, placing them in a polytonal rather than a strictly chromatic (Example 50), or serial setting (Example 51).

Example 50. Slonimsky: Thesaurus of Scales and Melodic Patterns, No. 649 [110]

Example 51. Stockhausen: Klavierstücke III, mm. 2–4 [111]

Example 52. Sandole: Polychords [112]

Fixed Pitch Classes

In some of his compositional devices, Sandole fixes notes within a specific range to provide for more deliberate bitonal and polytonal pitch relationships in harmony and melody. This concept of fixed register of assigned pitches was pioneered by Olivier Messiaen in his Canteyodjaya and Mode de Valeures et d’Intensités. [113] Sandole’s use of this device in jazz writing and composition/improvisation pedagogy is rare and could be viewed as a logical result of his tetrachordal approach. Example 53 illustrates Sandole’s fixed pitch concept using “Bitonal Scales” based on combining C diminished and A-2 (an A major tonality with a lowered second degree) sounds:

Example 53. Sandole: Bitonal Scales [114]

In this example, all B♮s are in the upper register and in general, all B♭s remain in the middle register as well as E♮s and E♭s, C♮s and C♯s, etc., and that by and large the position of each tone is generally held intact as per the original mode stated in measure one. The exceptions seem to be when a particular harmonic interval is desired as in the second measure where a C♮ is used in a higher range to create a series of descending perfect fourth intervals in whole steps, and where an E♭ is used in a higher register to create a minor ninth interval against a lower D♮. Also of note in this example is the predominant harmonic texture of minor ninth and perfect fourth intervals, the symmetry of the second and third tetrachords (the “Hungarian Major Altered” seen earlier in Example 34), and that the scale this device is based on is made up of all twelve tones.

Influence on John Coltrane’s Work

Much has been written about Dennis Sandole’s musical and personal relationship to his pupil John Coltrane. Below are quotes from various sources that describe Sandole’s influence on Coltrane’s musical and conceptual development:

By 1951 or 1952, John Coltrane was familiar with Nicolas Slonimsky’s Thesaurus of Scales and Melodic Patterns which he had learned about from his theory teacher Dennis Sandole, who was interested in scalar approaches to music. [115]

Sandole also exposed Coltrane to what the former called “exotic scales — scales from every ethnic culture.” Coltrane absorbed the principles of Nicolas Slonimsky’s influential Thesaurus of Scales and Melodic Patterns, but he also partook of Sandole’s Scale Lore, an unpublished book that differed from Slonimsky’s in that it was less analytical and more aural in approach; ...It embodied an open and eclectic outlook, which enhanced Coltrane’s own searching inclinations, his constant pursuit of new sounds, form, and technique. Coltrane hand-copied the book’s useful pages and evidently remained close to Sandole for many years. [116]

Sandole, a legendary figure, and teacher, became a mentor to Coltrane. Sandole remembers Coltrane fondly: “He used to take two legitimate (classical) lessons per week, not one. He was superbly prepared for each one. He was superlatively gifted, you know. I mostly teach a maturing of concepts, and it involves advanced harmonic techniques you can apply to any instrument. Coltrane went through eight years of my literature in four years. And we became excellent friends — we had dinner together once a week.” [117]

Coltrane was theory-mad. He had studied third-related harmonic relationships with Dennis Sandole at the Granoff School, and, as we have seen, there was a hint of the device in his composition “Nita,” recorded on Paul Chambers’ Whims of Chambers three years earlier. [118]

Theorist Donald Chittum states in his paper “Mozart, Wagner, and Coltrane,” that Coltrane’s “most important studies were done with Sandole,” and that “it is most probable that Sandole, more than anyone else, was responsible for Coltrane’s embarking on a study of classical music, especially that of the twentieth century.” [119] The topics Coltrane studied with Sandole, including but not limited to “pentatonic and modal scales, bitonality and polychordality, pedalpoint and cluster harmony, and harmony derived from melodic lines, a device closely associated with serial music,” [120] are among those areas Coltrane went on to innovate in concerning jazz improvisational practice. Sandole also had Coltrane practice from harp books to extend his range on the tenor saxophone [121] and might have been one of those that suggested the soprano saxophone to Coltrane. [122] It is also plausible that it was Sandole who introduced Coltrane to Slonimsky’s Thesaurus as this was a text with which Sandole was quite familiar [123] and one that Pat Martino learned about from Sandole during their brief studies in the late 1950s, which is where Martino himself met Coltrane. [124]

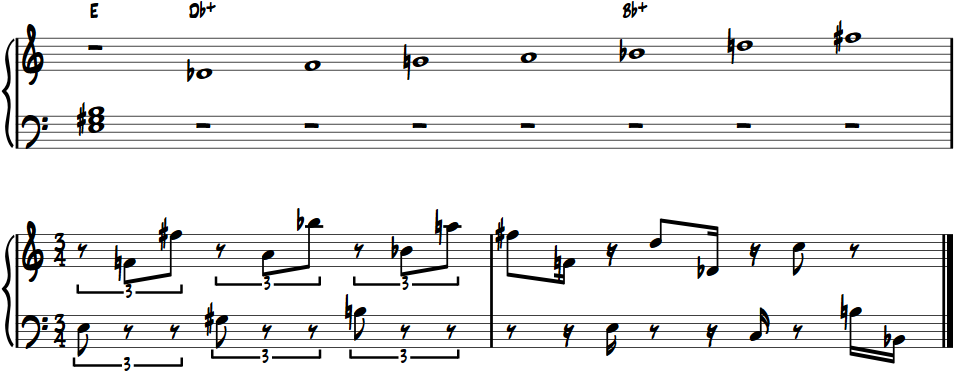

Example 54 is a handwritten sheet from John Coltrane notating some of Sandole’s harmonic principles. Coltrane’s writing is in print and Sandole’s is in cursive. This document was given to student Arnez Hayes by Sandole in 1993, who said that Sandole told him that Coltrane was “very young” when he wrote it, [125] perhaps indicating that the document dates back to his studies with Sandole at the Granoff Studios. Sandole makes reference to a similar document in Lewis Porter’s John Coltrane: His Life and Music regarding a handwritten document of Coltrane’s, stating, “I had substitute chords based on dominant to minor in (Coltrane’s) handwriting — he copied it. I found it in one of my old books, but I can’t find it anymore.” [126]

Example 54. Handwritten page of Dennis Sandole’s harmonic principles by John Coltrane [127]

In Coltrane’s later work, improvisational processes that are similar to concepts he studied with Sandole can be seen. For instance, in his thorough analysis of Coltrane’s “Venus” from Interstellar Space, Coltrane scholar and biographer Lewis Porter makes the following observations:

Nonetheless, it seems clear that Coltrane prefers to move among third-related keys to avoid a sense of tonal modulation — for example, E♭ and C, B and E♭, and to a lesser extent, E♭ and G♭, A♭ and C. He often connects these key areas by means of a repeated common tone — for example, E in the key of C is repeated, holding over into the key of B; G♯ in the key of B is then repeated to become A♭ in the key of E♭. [128]

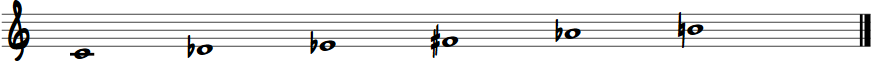

Porter’s transcription of the “Venus” solo illustrates this practice clearly. Example 51 is from line eight of the solo. There are no barlines or time signatures given and the key areas are labeled above the musical line:

Example 55. Excerpt from Lewis Porter transcription John Coltrane “Venus” solo [129]

In Example 56 from Sandole’s Scale Lore, we see bitonal scalar material that utilizes a variety of common tones in similar cycles as described above such as descending semitone relationship C major and B major combined with a common tone of E, and major and minor thirds relationships C major and A♭ major, C major and A major, C major and D♯/E♭ major, and C major and E major sharing an A note, mirroring the exact intervallic relationship of B major and E♭ major sharing a G♯/A♭ in the Coltrane example. In Example 53 from the “Polytonal Scale” section of the text (illustrated earlier in a truncated form as Ex. 37), Sandole states at the bottom of the page: “Make transition to next key on any note of previous key scale,” a statement that precisely describes Coltrane’s improvisational process within “Venus,” as illustrated by Porter:

Example 56a. Sandole: Scale Lore — excerpt from bitonal scales (C major and B major) [130]

Example 56b. Sandole: Scale Lore — excerpt from bitonal scales (C major and A♭ major) [131]

Example 56c. Sandole: Scale Lore — excerpt from bitonal scales (C major and A major) [132]

Example 56d. Sandole: Scale Lore — excerpt from bitonal scales (C major and D♯/E♭ major) [133]

Example 56e. Sandole: Scale Lore — excerpt from bitonal scales (C major and E major) [134]

Example 57. Sandole: Scale Lore — Polytonal scales [135]

According to student Bruce Eisenbeil, Sandole said that the last time he had seen Coltrane was in 1963, [136] and according to Joe Barrale, a longtime intimate friend and student of Sandole’s since the mid-1940s, Coltrane stayed in touch with Sandole for many years and remembers speaking to Coltrane himself on the phone at Sandole’s studio. Coltrane was calling to request that Sandole send him more lesson material by mail while he (Coltrane) was “in Japan,” and that payment was forthcoming, [137] which could mean that as late as his 1966 tour of Japan, Coltrane was continuing his studies with Sandole. All of this suggests that Sandole’s musical concepts and instruction were of significant influence on Coltrane’s creative output for a significant portion of his career, and that Coltrane valued both his personal and musical relationship with Sandole.

Conclusion

Dennis Sandole’s jazz pedagogy draws upon classical compositional theory in a unique way that allows for great creativity in melodic and harmonic invention for both himself and the student. Also, the student is exposed to a set of technical problems that cannot be found in any etude book that are written specifically for them. The extreme technical and conceptual demands that his jazz improvisation literature represented attracted many cutting edge virtuoso jazz practitioners as demonstrated by the impressive and varied roster of students that he taught. Joe Sgro, a legendary Philadelphia jazz guitarist/pedagogue (and cousin of jazz violinist Joe Venuti), characterized Sandole as “the Schoenberg of the jazz world, a tremendous musician” [138] seemingly referring to his compositional, theoretical, and pedagogical prowess and originality.

Through his teaching literature, Sandole demonstrated endless invention in the creation of scalar and chordal material and an uncommon gift in composing and demonstrating the application of these harmonic and melodic materials in the modern jazz vernacular. His pedagogical methodology differs significantly from traditional jazz improvisation pedagogy such as chord/scale relationship methods, and yet his literature can be used in this way if so desired. The sheer volume of pitch and harmonic material he organized and utilised was immense and his ability to cater each lesson to a particular student’s musical needs is remarkable and reveals a lifelong dedication to helping each student find their own voice.

In addition, his influence on John Coltrane is significant, and it is possible that, through their close musical relationship, his theories have impacted and shaped modern jazz vernacular and practice in a substantial way. Leaving “his fingerprints all over the jazz history book,” [139] Dennis Sandole is a remarkably original figure in the history of jazz theory and pedagogy whose teachings have influenced a significant amount of important jazz musicians many of whom are still making music today. His work is worthy of further academic inquiry and study.

Bibliography

- Arden, Joseph. “Focussing the Musical Imagination: Exploring in Composition the Ideas and Techniques of Joseph Schillinger.” PhD diss., City University, London, 1996. Accessed June 13, 2012. http://januszpodrazik.com/downloads/Schillinger.pdf

- Bailey, Kathryn. The Life of Webern. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Baker, David. The Jazz Style of John Coltrane: A Musical and Historical Perspective. Lebanon, IN: Studio 224, 1980.

- “Bassist Jeff Berlin Pays Tribute to Charlie Banacos.” All About Jazz, December 24, 2009. Accessed February 21, 2013. http://www.allaboutjazz.com/php/article.php?id=35119#.USZRIaXOHAA.

- “Billy Newman — Jazz and Brazilian Guitarist.” Accessed July 9, 2012. http://www.billynewman.com/sandole.shtml

- Boulez, Pierre, John Cage, and Jean-Jacques Nattiez. The Boulez–Cage Correspondence. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- Capuzzo, Guy. “Pat Martino and ‘The Nature of the Guitar’: An Intersection of Neo-Riemannian Theory and Jazz Theory.” Music Theory Online 1, no. 12 (2006): 1–17. Accessed November 4, 2012. http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.06.12.1/mto.06.12.1.capuzzo.pdf

- Carter, Elliott, Nicholas Hopkins, and John F. Link, Harmony Book. New York: Carl Fischer, 2009.

- Chittum, Donald. “Mozart, Wagner, and Coltrane.” paper presented at The International Association of Jazz Educators, New York, NY, January 10, 2007.

- Collier, James Lincoln. The Making of Jazz: A Comprehensive History. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1978.

- “Coltrane’s Mentor Was Legendary Jazz Teacher,” The Last Post/The Scotsman, 2000. Accessed April 15, 2012. http://www.jazzhouse.org/gone/lastpost2.php3?edit=971426621

- Cook, Nicholas. “Analyzing Serial Music” in A Guide to Musical Analysis. New York: George Braziller, 1987.

- Covach, John. “Twelve Tone Theory” in The Cambridge History of Western Music Theory. ed. Thomas Christensen. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- “Dennis Sandole, pt. 1 and pt. 2.” Miles of Music. Directed by Bob Miles. Produced by Bob Miles. 2006. Middle Bucks Institute of Technology, PA: Cable Access.

- Edlund, Lars. Modus Novus: Lärobok i fritonal melodiläsning = Lehrbuch in freitonaler Melodielesung = Studies in reading atonal melodies. Stockholm: Nordiska musikförlaget, 1964.

- Foley, Gretchen. Pitch and Interval Structures in George Perle’s Theory of Twelve-Tone Tonality. Thesis (PhD), University of Western Ontario, London, 1998, 1999. Accessed March 3, 2012. http://www.nlc-bnc.ca/obj/s4/f2/dsk1/tape9/PQDD_0014/NQ40259.pdf

- Golson, Benny. Interviewed by Anthony Brown for The National Endowment of The Arts, Smithsonian National Museum of American History, January 8–9, 2009, p. 33–34. Accessed July 22, 2012. http://www.smithsonianjazz.org/oral_histories/pdf/Golson.pdf

- Hába, Alois and Suzette Mary Battan. New Theory of Harmony: of the Diatonic, the Chromatic, the Quarter Tone, the Third Tone, the Sixth Tone, and the Twelfth Tone Systems. Leipzig: Fr. Kistner & C.F. W. Siegel, 1927. Accessed Dec. 11, 2011, UR Research at The University of Rochester, http://hdl.handle.net/1802/2896

- Hyde, Martha. “Dodecaphony: Schoenberg.” in Models of Musical Analysis, 1st ed., 56–80. Oxford: Blackwell, 1993. Accessed July 21, 2012. http://www.musictheory21.com/documents/readings-in-music-theory/hyde-dodecaphony-schoenberg.pdf

- Johnson, Barrett. Training the Composer: A Comparative Study between the Pedagogical Methodologies of Arnold Schoenberg and Nadia Boulanger. Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars Pub., 2010.

- Johnson, Robert Sherlaw. Messiaen. London: Omnibus Press, 1989.

- Kordis, Lefteris. “Top Speed and in All Keys”: Charlie Banacos’s Pedagogy of Jazz Improvisation. Thesis (D.M.A.)--New England Conservatory, 2012. Accessed September 23, 2012. http://www.charliebanacos.com/Kordis_DMA_Dissertation_2012.pdf

- Krenek, Ernst. Studies in Counterpoint; Based on the Twelve-Tone Technique. New York: G. Schirmer, 1940.

- Lateef, Yusef. Repository of Scales and Melodic Patterns. Amherst, MA: Fana Music, 1981.

- Lehman, Andreas, and K. Anders Ericsson. “Research on Expert Performance and Deliberate Practice: Implications for the Education of Amateur Musicians and Music Students.” Psycomusicology 16 (1997): 40–58. Accessed July 8, 2012. http://blade2.vre.upei.ca/ojs/index.php/psychomusicology/article/view/465/612

- Lendvai, Ernő. Béla Bartók: An Analysis of His Music. London: Kahn & Averill, 1971.

- Martin, Henry. “More Than Just Guide Tones: Steve Larson’s ‘Analyzing Jazz — A Schenkerian Approach’.” Journal of Jazz Studies 7, no. 1 (2011): 121–144. Accessed February 18, 2013. http://jjs.libraries.rutgers.edu/index.php/jjs/article/view/7/15

- Martino, Pat, and Tony Baruso. Linear Expressions. Milwaukee, WI: Hal Leonard, 1983.

- Martino, Pat, and Bill Milkowski. Here and Now!: The Autobiography of Pat Martino. Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books, 2011.

- Moon, Tom. “Dennis Sandole, Educator Who Taught Giants of Jazz,” Philly.com Online, October 4, 2000. Accessed 25 April, 2012. http://articles.philly.com/2000-10-04/news/25584730_1_jazz-guitarist-rufus-harley-saxophonist-brother

- “Outside Pants: Reflections On Studying With Dennis Sandole.” Outside Pants. Accessed September 7, 2012. http://outsidepants.blogspot.co.uk/2011/02/reflections-on-studying-with-dennis.html

- Perle, George. Serial Composition and Atonality, Sixth Edition. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- ———. Twelve-Tone Tonality, Second Edition. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996.

- Persichetti, Vincent. Twentieth Century Harmony: Creative Aspects and Practice. New York: W.W. Norton & Company Inc., 1961.

- Porter, Lewis. John Coltrane: His Life and Music. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1999.

- Ratliff, Ben. “Dennis Sandole: Jazz Guitarist and an Influential Teacher, 87,” The New York Times Online, October 8, 2000. Accessed April 25, 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2000/10/08/nyregion/dennis-sandole-jazz-guitarist-and-an-influential-teacher-87.html

- Russell, George. George Russell’s Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization Volume One, The Art and Science of Tonal Gravity. Brookline, MA: Concept, 2001.

- Sandole, Adolph. Fourth Chords and Scales. Bryn Mawr: Theodore Presser, 1982.

- ———. The Craft of Jazz I: Apprentice. New York: Adolph Sandole, 1979.

- ———. The Craft of Jazz II: Journeyman. New York: Adolph Sandole, 1977.

- Sandole, Dennis. Guitar Lore. Philadelphia: Theodore Presser, 1999.

- Schillinger, Joseph. Kaleidophone; New Resources of Melody and Harmony; Pitch Scales in Relation to Chord Structures; an Aid to Composers, Performers, Arrangers, Teachers, Song-Writers, Students, Conductors, Critics and All Who Work with Music. New York: M. Witmark & Sons, 1940.

- Schoenberg, Arnold. Theory of Harmony, Third Edition. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978.

- Shim, Eunmi. Lennie Tristano: His Life in Music. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2007.

- Shipp, Matthew. “Guest Post: Matthew Shipp’s tribute to teacher Dennis Sandole | destination: OUT.“ destination: OUT, February 7, 2011. Accessed September 7, 2012. http://destination-out.com/?p=2264.

- Slawek, Stephen. “Hindustani Sitar and Jazz Guitar Music: A Foray Into Comparative Improvology” in Musical Improvisation: Art, Education, and Society, ed. Gabriel Solis and Bruno Nettl. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2009.

- Slonimsky, Nicolas. Music Since 1900. London: J. M. Dent and Sons Ltd, 1938.

- ———. Thesaurus of Scales and Melodic Patterns. New York: Schirmer Books, 1947.

- Solomon, Larry. “Symmetry as a Compositional Determinant: Chpt. VII: Analysis of Works with Intensive Applications.” PhD diss., West Virginia University, 1973, revised 2002. Accessed July 13, 2012. http://solomonsmusic.net/diss7.htm

- Straus, Joseph Nathan. Twelve-Tone Music in America. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Thomas, J. C. Coltrane: Chasin’ the Trane. New York: Da Capo Press Inc., 1975.

- Tymoczko, Dimitri. “The Consecutive Semitone Constraint on Scale Structure: A Link Between Impressionism and Jazz.” Integral 11 (1997): 135–179. Accessed December 2, 2012. http://dmitri.tymoczko.com/files/publications/consecutivesemitone.pdf

- Umholtz, Damon. “Dennis Sandole | Free Music, Tour Dates, Photos, Videos.” Welcome to the new Myspace!. Last modified August 7, 2009. Accessed February 25, 2013. http://www.myspace.com/dennissandole

- Varga, Bálint András. Three Questions for Sixty-Five Composers. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 2011.

- Whaley, Preston. Blows Like a Horn: Beat Writing, Jazz, Style, and Markets in the Transformation of U.S. Culture. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004.

References

[1] Benny Golson, Interviewed by Anthony Brown for The National Endowment of The Arts, Smithsonian National Museum of American History, January 8–9, 2009, p. 33–34. Accessed July 22, 2012. http://www.smithsonianjazz.org/oral_histories/pdf/Golson.pdf.

[2] Lewis Porter, John Coltrane: His Life and Music (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1999), 51.

[3] Stephen Slawek, “Hindustani Sitar and Jazz Guitar Music: A Foray Into Comparative Improvology” in Musical Improvisation: Art, Education, and Society, ed. Gabriel Solis and Bruno Nettl, Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2009), 204.

[4] Bruce Eisenbeil (Sandole guitar student). 2012. Telephone interview by the author. Digital recording. December 18.

[5] Ben Ratliff, “Dennis Sandole: Jazz Guitarist and an Influential Teacher, 87,” The New York Times Online, October 8, 2000. Accessed April 25, 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2000/10/08/nyregion/dennis-sandole-jazz-guitarist-and-an-influential-teacher-87.html

[6] “Coltrane’s Mentor Was Legendary Jazz Teacher,” The Last Post/The Scotsman, 2000. Accessed April 15, 2012. http://www.jazzhouse.org/gone/lastpost2.php3?edit=971426621

[7] Joseph Barrale (Sandole guitar student and close friend). 2012. Telephone interview by the author. Digital recording. June 28.

[8] “Coltrane’s Mentor Was Legendary Jazz Teacher.”

[9] Tom Moon, “Dennis Sandole, Educator Who Taught Giants of Jazz,” Philly.com Online, October 4, 2000. Accessed 25 April, 2012. http://articles.philly.com/2000-10-04/news/25584730_1_jazz-guitarist-rufus-harley-saxophonist-brother; “Coltrane’s Mentor Was Legendary Jazz Teacher.”

[10] Craig Thomas (Sandole bass student). 2012. Telephone interview by the author. Digital recording. December 6.

[11] Ratliff, “Dennis Sandole: Jazz Guitarist and an Influential Teacher, 87.”

[12] Porter, John Coltrane: His Life and Music, 51–52.

[13] Joseph Barrale.

[14] Ibid.

[15] The Brothers Sandole: Modern Music From Philadelphia (Fantasy 3-209, 1955) reissued as The Sandole Brothers & Guests (Fantasy FCD 24763-2, 2001, Compact disc)

[16] The Dennis Sandole Project (Cadence Jazz Records CJR 1102, 1999, Compact disc)

[17] Charlie Barnet Orchestra: Drop Me Off In Harlem — The Original Decca Recordings (GRP 16122, 1992, Compact disc)

[18] James Moody: Running The Gamut (Scepter Records 525, 1964)

[19] Art Farmer: The Many Faces Of Art Farmer (Scepter Records 521, 1964)

[20] Moon, “Dennis Sandole, Educator Who Taught Giants of Jazz.”; “Coltrane’s Mentor Was Legendary Jazz Teacher.”; Joseph Federico (Sandole guitar student and close friend). 2012. Telephone interview by the author. Digital recording. June 21.

[21] Bobby Zankel (Sandole alto saxophone student). 2012 Telephone interview by the author. Digital recording. November 30.

[22] Craig Thomas.

[23] Moon, “Dennis Sandole, Educator Who Taught Giants of Jazz.”

[24] Bruce Eisenbeil.

[25] Moon, “Dennis Sandole, Educator Who Taught Giants of Jazz.”

[26] Joseph Federico.

[27] Bruce Eisenbeil.

[28] Craig Thomas.

[29] Joseph Federico.

[30] Matthew Shipp, “Guest Post: Matthew Shipp’s tribute to teacher Dennis Sandole | destination: OUT.“ destination: OUT, February 7, 2011. Accessed September 7, 2012. http://destination-out.com/?p=2264.

[31] Rufus Harley, personal conversation with the author, 1997.

[32] Shipp, “Guest Post: Matthew Shipp’s tribute to teacher Dennis Sandole.”

[33] Bobby Zankel.

[34] Dennis Sandole, personal conversation with the author, 1990.

[35] Dennis Sandole, Dennis Sandole Teaching Procedure (Philadelphia, 1994).

[36] Ibid.

[37] The author was a student of Mr. Sandole from December 1990 until his passing in 2000. The following four-week lesson cycle has been taken from lesson notebooks from 1992 and the material was written specifically for the guitar. All of the musical terminology used in this paper to describe Sandole’s lesson examples is his, and the lesson material has been rewritten in notation software as authentically as possible, adhering to Sandole’s original freehand notation.

[38] Dennis Sandole, private lesson material for the author, 1992.

[39] T. Scott McGill, private lesson material for Dennis Sandole studies, 1992.

[40] Dennis Sandole, Guitar Lore (Philadelphia: Theodore Presser, 1999), 66.

[41] Sandole, private lesson material for the author

[42] McGill, material for Sandole studies.

[43] Sandole, private lesson material for the author.

[44] Sandole, Guitar Lore, 34.

[45] McGill, material for Sandole studies.

[46] Sandole, private lesson material for the author.

[47] McGill, material for Sandole studies.

[48] Sandole, private lesson material for the author.

[49] Ibid.

[50] McGill, material for Sandole studies.

[51] Sandole, Latin American Rhythms, Philadelphia.

[52] McGill, material for Sandole studies.

[53] Ibid.

[54] Vincent Persichetti, Twentieth Century Harmony: Creative Aspects and Practice (New York: W.W. Norton & Company Inc., 1961), 48.

[55] Sandole, private lesson material for the author.

[56] McGill, material for Sandole studies.

[57] Lars Edlund, Modus Novus: Lärobok i fritonal melodiläsning = Lehrbuch in freitonaler Melodielesung = Studies in reading atonal melodies. (Stockholm: Nordiska musikförlaget, 1964), 57.

[58] McGill, material for Sandole studies. McCoy Tyner, “Inception” from McCoy Tyner: Inception, ©1962 GRP/Impulse! IMPD 220, Compact disc.

[59] McGill, material for Sandole studies. Anton Webern, String Quartet Opus 28. (Vienna, Universal Edition, 1990).

[60] McGill, material for Sandole studies. Wayne Shorter, “Fall”, from Miles Davis: Nefertiti, ©1968/1990 Sony Music Entertainment Inc., Columbia 467089 2, Compact disc.

[61] Ibid.

[62] Ibid.

[63] Nicolas Slonimsky, Thesaurus of Scales and Melodic Patterns (New York: Schirmer Books, 1947), 34.

[64] McGill, material for Sandole studies. Shorter, “Fall”, Davis: Nefertiti.

[65] Ibid.

[66] Dennis Sandole, personal conversation with the author, 1990s.

[67] Sandole, private lesson material for the author.

[68] McGill, material for Sandole studies.

[69] Dennis Sandole, Scale Lore (Philadelphia).

[70] Persichetti, Twentieth Century Harmony, 48.

[71] Sandole, private lesson material for the author, 1990.

[72] John Covach, “Twelve Tone Theory” in The Cambridge History of Western Music Theory. ed. Thomas Christensen (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2002). Accessed March 3, 2011. http://www.musictheory21.com/documents/readings-in-music-theory/covach-twelve-tone-theory-pp.603-627.pdf, 613–617.

[73] Dennis Sandole, private lesson material for the alto saxophone, 1998, used with permission from Bobby Zankel.

[74] Sandole, private lesson material for the author, 1994.

[75] Ibid.

[76] Sandole, private lesson material for the author, 1991.

[77] Sandole, private lesson material for the author, 1995.

[78] Ernő Lendvai, Béla Bartók: An Analysis of His Music (London: Kahn & Averill, 1971), 40.

[79] George Perle, Serial Composition and Atonality, Sixth Edition (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University), 40.

[80] Slonimsky, Thesaurus of Scales and Melodic Patterns, 34.

[81] Alexander Scriabin, Piano Sonata No. 7, Op. 64 (Editions Peters #12652, 1972).

[82] Don Glanden, “Analysis of Chick Corea’s Solo — 500 Miles High,” [September 28, 2009], Video clip. Accessed June, 16, 2012. YouTube, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NE33Kz6_DT4. “500 Miles High” from Return To Forever: Light As A Feather, ©1973 Polydor 827-148-2, Compact disc.

[83] Dennis Sandole, private lesson material for piano, 1995.

[84] J. C. Thomas, Coltrane: Chasin’ the Trane (New York: Da Capo Press Inc., 1975), 51.

[85] Elliott Carter, Nicholas Hopkins, and John F. Link, Harmony Book (New York: Carl Fischer, 2009), 352.

[86] Alois Hába and Suzette Mary Battan, New Theory of Harmony: of the Diatonic, the Chromatic, the Quarter Tone, the Third Tone, the Sixth Tone, and the Twelfth Tone Systems (Leipzig: Fr. Kistner & C.F. W. Siegel, 1927), Accessed Dec. 11, 2011, UR Research at The University of Rochester, http://hdl.handle.net/1802/2896, 8.

[87] Sandole, Scale Lore.

[88] Larry Solomon, “Symmetry as a Compositional Determinant: Chpt. VII: Analysis of Works with Intensive Applications” (PhD diss., West Virginia University, 1973, revised 2002). Accessed July 13, 2012. http://solomonsmusic.net/diss7.htm.

[89] Sandole, private lesson material for the author, 1994.

[90] Thomas, Coltrane: Chasin’ the Trane, 53.

[91] Ibid, 54.

[92] Bela Bartok, String Quartet III, (London, Universal Edition, 1929).

[93] McGill, material for Sandole studies, 1996.

[94] Hába and Battan, New Theory of Harmony, 52–53, 70–71.

[95] Joseph Arden, “Focussing the Musical Imagination: Exploring in Composition the Ideas and Techniques of Joseph Schillinger” (PhD diss., City University, London, 1996). Accessed 13 June, 2012. http://januszpodrazik.com/downloads/Schillinger.pdf, 31–32.

[96] Dennis Sandole, private lesson material for piano, 1995.

[97] Craig Thomas.

[98] Joseph Barrale.

[99] Sandole, Guitar Lore, 65–66.

[100] Sandole, private lesson material for the author, 1990–91.

[101] Perle, Serial Composition, 41.

[102] Dennis Sandole, private lesson material for piano, 1997.

[103] Ibid.

[104] Ibid.

[105] Robert Sherlaw Johnson, Messiaen (London: Omnibus Press, 1989), 90,93.

[106] Dennis Sandole, private lesson material for piano, 1997.

[107] Hába and Battan, New Theory of Harmony, 122–125.

[108] Johnson, Messiaen, 94.

[109] Dennis Sandole, private lesson material for piano, 1997.

[110] Slonimsky, Thesaurus of Scales and Melodic Patterns, 90.

[111] Karlheinz Stockhausen, Nr. 2, Klavierstücke I–IV, (London: Universal Edition, 1954).

[112] Dennis Sandole, private lesson material for the alto saxophone, 1998, used with permission from Bobby Zankel.

[113] Johnson, Messiaen, 104–107.

[114] Sandole, private lesson material for the author, 1997.

[115] James Lincoln Collier, The Making of Jazz: A Comprehensive History (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1978), 432.

[116] Preston Whaley, Blows Like a Horn: Beat Writing, Jazz, Style, and Markets in the Transformation of U.S. Culture (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004), 187.

[117] Porter, John Coltrane: His Life and Music, 51.

[118] Ben Ratliff, Coltrane: The Story of a Sound, (London: Faber & Faber, 2007), 51–52.

[119] Donald Chittum, “Mozart, Wagner, and Coltrane” (paper presented at The International Association of Jazz Educators, New York, NY, January 10, 2007), 6–7.

[120] Ibid, 7.

[121] “Guest Post: Matthew Shipp’s tribute to teacher Dennis Sandole,” destination: OUT.

[122] Thomas, Coltrane: Chasin’ the Trane, 54.

[123] Craig Thomas.

[124] “Pat Martino.” YouTube. Accessed May 24, 2012. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COyOxqyEeTs&feature=related.

[125] Arnez Hayes, e-mail correspondence to author, March 7, 2013.

[126] Porter, John Coltrane: His Life and Music, 51.

[127] Arnez Hayes, e-mail correspondence to author, April 14, 2012, used with permission.

[128] Porter, John Coltrane: His Life and Music, 280.

[129] Ibid, 283.

[130] Sandole, Scale Lore.

[131] Ibid.

[132] Ibid.

[133] Ibid.

[134] Ibid.

[135] Ibid.

[136] Bruce Eisenbeil.

[137] Joseph Barrale (Sandole guitar student and close friend). 2013. Telephone interview by the author. Digital recording. March 2.

[138] Slawek in Solis & Nettl, 204–205.

[139] Moon, “Dennis Sandole, Educator Who Taught Giants of Jazz.”

Author Information:

Thomas Scott McGill is an international jazz/progressive fusion recording artist working with Michael Manring and Percy Jones (Brand X). In addition to having spent ten years of postgraduate study with Dennis Sandole, McGill holds degrees from Temple University and Middlesex University. He is a longtime monthly magazine columnist for Guitar Techniques (UK) and Guitar Player (US/Canada), and is the B.A. (Hons) Course Leader at the Brighton Institute of Modern Music. McGill is author of Twelve-Tone Octave Displacement Studies for The Guitar and All Treble Clef Instruments and co-author of The Guitar Arpeggio Compendium.

Abstract:

Philadelphia-based teacher, theorist, performer, and composer Dennis Sandole is perhaps best known for having been John Coltrane’s theory and improvisation teacher and mentor. A guitar virtuoso, Sandole also developed a conceptually advanced and technically demanding teaching literature that was strongly influenced by twentieth century classical compositional practice. This article examines Sandole’s teaching approach, which applied a range of highly sophisticated melodic and harmonic techniques to the jazz idiom, including exotic scales, chord progressions, and substitutions based on interval cycles, polytonality, and synthetic multi-octave scales. It also considers the influence that his teachings exerted on John Coltrane’s musical output.

Keywords:

Dennis Sandole, John Coltrane, guitar, improvisation, pedagogy, Philadelphia, music theory, jazz

How to cite this article:

- Chicago 15th ed.: McGill, Thomas Scott. “Dennis Sandole’s Unique Jazz Pedagogy.” Current Research in Jazz 5, (2013).

- MLA 7th ed.: McGill, Thomas Scott. “Dennis Sandole’s Unique Jazz Pedagogy.” Current Research in Jazz 5 (2013). Web. [date of access]

- APA 6th ed.: McGill, T. S. (2013). Dennis Sandole’s Unique Jazz Pedagogy. Current Research in Jazz, 5 Retrieved from http://www.crj-online.org/

For further information, please contact: