Willis Conover’s Washington

Maristella Feustle

It is a well-established fact that broadcaster Willis Conover’s long-running Voice of America radio program, Music USA, was a highly successful and influential use of music in public diplomacy. Conover’s program, which ran from 1955 until his death in 1996, fostered a genuine “people-to-people” connection between two superpowers estranged by the Cold War, cultivating audiences of listeners as well as jazz musicians whose first reliable access to jazz was Conover’s nightly program. Conover was a 1995 recipient of Down Beat magazine’s lifetime achievement award, and his obituary in The New York Times went so far as to say that, “In the long struggle between the forces of Communism and democracy, Mr. Conover, who went on the air in 1955 and continued broadcasting until a few months ago, proved more effective than a fleet of B-29’s.” [1]

More understated appraisals also recognize Conover’s contributions to musical diplomacy and the global propagation of jazz. Penny von Eschen notes that recordings of Conover’s program sold on the Moscow black market in 1962 for as much as 40 rubles (about 44 U.S. dollars). [2] Danielle Fosler Lussier notes that Conover’s broadcasts helped prepare the ground for later State Department-sponsored tours by jazz artists in cultivating a “small community of dedicated fans,” noting that “The existence of these expert fans was likely due to another U.S. propaganda effort: the broadcasting of American music on Voice of America radio, especially Willis Conover’s Music USA.” [3]

By contrast, Conover’s ten-year career in Washington, D.C. prior to joining the Voice of America is virtually forgotten, but during those years he built the connections with jazz musicians, gained the concert promotion experience, and developed the on-air persona which led to his success at the VOA. Understandably, existing research on Conover has focused on his Cold War contributions: Gene Lees devotes a chapter to Conover in his autobiography, but with a brief mention of Conover’s early career; [4] Terence Ripmaster’s 2007 biography of Conover treats his post-war work before the Voice of America in passing; [5] Mark Breckenridge’s 2012 dissertation emphasizes the 1960s; [6] one more extended piece by Ron Fritts, discussing Conover in the 1940s appears in the CD insert of Charlie Parker — Washington D.C., 1948. [7] But there has not been a comprehensive treatment of Conover’s early career.

Therefore, this article chronicles that formative decade which set the stage for Music USA and shows how extensively Conover drew upon his own personal resources and relationships to ensure the program’s success. The Willis Conover whom “the rest of the world” came to know first made his mark in Maryland and Washington, D.C.

Born on December 18, 1920 in Buffalo, New York, Conover discovered his talent for radio announcing before he discovered jazz. In a 1994 interview with Billy Taylor for the Smithsonian Institution’s Jazz Oral History Project, he explained:

When I was a high school freshman, an upperclassman wrote a skit that took place, presumably, in a radio station, and because my voice had changed they gave me the role of the radio announcer to read phony commercials and so forth. So when it was all over, people came up to me and said, “Hey, you sound just like a real radio announcer!” Well, you know, when you’re about, whatever I was, about fourteen or something, well, it sticks in your mind. [8]

During his single year of college at Salisbury State Teachers College in Maryland in 1938 and 1939, he began working at the campus station, WSAL. After winning an announcer’s contest in Washington, D.C., he was offered a job at WTBO in Cumberland, Maryland, and it was in Cumberland that hearing Billy May’s arrangement of Ray Noble’s “Cherokee” first sparked his interest in jazz, quickly leading to his discovery of Duke Ellington’s music. [9]

Peg Lynch and Willis Conover, circa 1940.

(From the Willis Conover Collection, UNT Music Library.)

Conover rose in the ranks of WTBO to Chief Announcer and music director, with the astounding salary of $37.50 a week. He enjoyed modest success in the local theater scene and played Albert in an early incarnation of the sitcom Ethel and Albert alongside the groundbreaking writer and actress Peg Lynch. [10] He was inducted into the Army in September of 1942, where his experience interviewing people on the radio led to a position as a classification specialist at Fort Meade, interviewing new recruits to match them with suitable duties. [11]

While still in the Army, he caught a major break at the Stage Door Canteen in Washington, D.C. simply by seeing a need and doing something about it. The music which someone else had picked out for an evening of dancing was just not cutting it. Conover selected and played replacements which were so well received that he obtained a part-time position at WWDC in Washington, D.C., working weekends at the station and spending the rest of the week with the Army. [12] Broadcasting magazine of December 24, 1945 has Conover doing “poetic interludes” on a program with former Kay Kyser soloist Ted Alexander, in what advertisers called “a fifteen-minute show that has both bobby-soxers and matrons swooning.” [13]

By the time of his honorable discharge from the Army at the rank of Technical Sergeant in February of 1946, Conover was serving WWDC in a variety of ways. [14] Calling upon his background in theater and radio comedy, he starred as Harold alongside Nathalie Sherman in a possible derivative of Peg Lynch’s Ethel and Albert, entitled Hazel and Harold, with lightheartedly topical plotlines like nightmares about rationed kisses. [15] His role in music quickly overtook his role as an actor, however; on March 10, 1946, The Washington Post announced that “Now that Willis Conover is no longer Government property, he will devote full time to WWDC. ‘The Tune Shop’ under his auspices, starts at 9:15 a.m. on a daily basis.” [16] Radio listings show that it was a 45-minute program — a substantial amount of airtime. [17]

Willis Conover, Duke Ellington, Billy Strayhorn, and others, April

1946. (From the Willis Conover Collection, UNT Music Library.)

On April 20, 1946, Conover scored a major coup in interviewing Duke Ellington and his entourage in connection with a performance in the area. The recording survives in the Willis Conover Collection at the University of North Texas and in the Ruth Ellington Collection at the Smithsonian Institution, and the tone of the interview is very friendly and humorous, not at all stiff or formal. Weeks later, Conover also featured Lionel Hampton in person, [18] and on June 6 of that year, Conover emceed Ellington’s appearance at the Watergate Barge, a venue on the Potomac River near the Lincoln Memorial. It was the first time an African-American artist had performed there. [19] When Ellington appeared at New York’s Carnegie Hall in November of 1946, Conover was his emcee. [20] Several selections from that concert were used on V-Discs (742, 750, 759), but with introductions recorded by Leonard Feather on the first two.

That same year, Conover leveraged other connections to send his younger sister, Elizabeth, a unique wedding gift, having Nat “King” Cole congratulate the new couple and play a few select tunes dedicated to them on the radio with his trio (that recording also survives at UNT, and is available online), [21] Conover continued interviewing top names in jazz on WWDC; Stan Kenton, Peggy Lee, and George Shearing are other artists whose appearances survived on broadcast transcriptions at UNT.

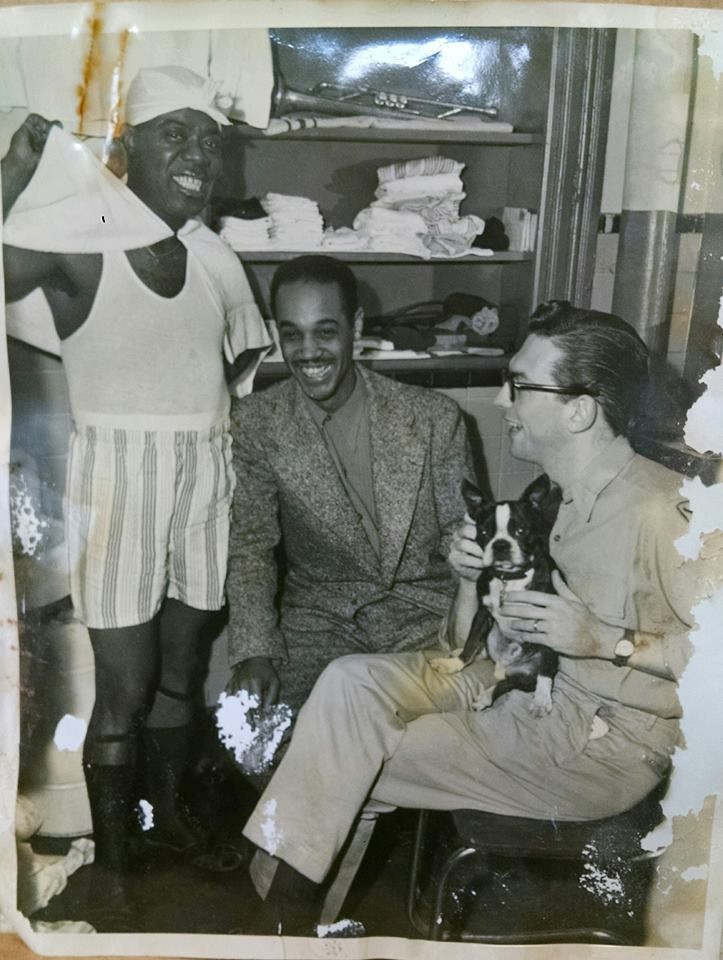

Willis Conover backstage with Louis Armstrong

and Mercer Ellington.

(From the Willis Conover Collection, UNT Music Library.)

During that time, Conover also established himself as a concert promoter. The Washington Post noted that he had, by early 1951, emceed concerts featuring Louis Armstrong, Charlie Parker, Woody Herman, Stan Kenton, Billy Eckstine, George Shearing, and Ralph Flanigan. [22] It was also Conover who heard Ruth Brown singing at Blanche Calloway’s Club Crystal Caverns in Washington, D.C., and recommended her to Ahmet Ertegun of Atlantic Records. [23]

Conover also made use of his position as a concert promoter to break down the color barrier in the segregated club scenes of Washington, D.C. Racial “mixing” was forbidden by law in the city; in practice, white patrons could go to black clubs, but the reverse was absolutely forbidden. Still, Conover would not abide by rules he found absurd. He recalled in the 1994 Smithsonian oral history:

If I went to see Art Tatum, for example, after he played he couldn’t come and sit with me at the table. He and I would have to go upstairs to his dressing room and talk there.

I made a deal with every place where I presented music. I said, “Look: I will not advertise the event in the Afro American newspaper. I’ll be buying ads in The Washington Times Herald, and The Washington Post, and The Washington Star, and so forth, and talking about it on my program, but you, regardless of the law in this town, will admit anyone who is as properly dressed and properly behaved as the rest of the people.” And so they agreed, and my events were the first integrated downtown events.

I remember one time when Billie Holiday was singing, uptown, in the black part of town, and Art Tatum was downtown playing, and she said to me, “Willis, I’d sure love to see Art Tatum.” So I went to the manager of the club and said, “Hey, listen, Billie Holiday wants to come and see Art Tatum. Can I bring her or not?” He said, “Well, you can bring her for one set, but you can’t have anything to drink!” [24]

In 1979, Conover recalled that the club in question was Olivia Davis’ Merry-Land Club of 1405 L Street, NW, in Washington, D.C., [25] where he hosted a fifteen-minute radio show in 1949. [26]

By 1949, Conover was also known to the Voice of America, over six years before the beginning of Music USA. The aforementioned Washington Post article from 1951 notes that “The State Department has used Conover on ‘Voice of America’ broadcasts on American Jazz,” [27] and a Voice of America broadcast transcription entitled American Jazz #1 survives in the UNT collection. On the recording, dated August 23, 1949, Conover presents a survey of Duke Ellington’s music, reading his comments in English, followed by an unidentified narrator reading a translation in Swedish.

Almost immediately following that date, The Washington Post noted on September 4, 1949, that “Willis Conover, WWDC expert on swing and jazz, is on a busman’s holiday. He’s traveling with Duke Ellington’s orchestra during the next two weeks, to add to his knowledge of jazz lore.” [28] It is possible to pinpoint Ellington’s itinerary during that time. The band began September at the Click Club in Philadelphia, continuing to Buffalo (Conover’s hometown), Toronto and Sudbury, Ontario, and New York City. [29] Regrettably, the online Ellingtonia discography shows a gap between September 4 and 19 for released recordings, [30] but it is possible to hear the band Conover heard on the Raretone release Live At Click Restaurant Philadelphia 1949, Vol. 4 (5005-FC) and AFRS JJ-83.

Conover’s rise as a radio personality continued; he was sometimes dubbed the “Gentleman Jockey.” In 1950, he was voted the top local disc jockey “by radio and TV editors of newspapers in [the] Washington area.” [31] He again found himself on two government-sponsored projects, serving as announcer for Treasury Guest Star broadcasts featuring Duke Ellington (#203) and Art Tatum (#222). Tatum was, in fact, booked because of an appearance on Conover’s program on WWDC, as “Nate Colwell, a jazz enthusiast and chief of the Treasury Department’s radio division, heard the program and phoned Tatum and Conover to come down to the department immediately to record.” [32]

Willis Conover, the “Gentleman Jockey,” judges a beauty

pageant. (From the Willis Conover Collection, UNT Music Library.)

As television stations proliferated, Conover began appearing on screen as well, at WNBW (now WRC), Washington’s NBC affiliate, around 1951. Conover’s presence there became historical footnote in an early congressional “morals inquiry” into radio and television programming, described in a two-page report in the June 9, 1952 issue of Broadcasting magazine. [33] As a subcommittee of the House Interstate and Foreign Commerce Committee listened, one witness’s laundry list of offenses logged from an afternoon and evening of viewing on WNBW included “some very low necklines on ‘The Willis Conover Show,’ dropped almost off the shoulders.” [34]

In the early 1950s, Conover co-founded an all-star ensemble known as The Orchestra of Washington, D.C., with drummer and bandleader Joe Timer (originally “Theimer”). Conover explained in a 1983 Washington Post article that “Some musicians who had been on the road with Buddy Rich, Elliot Lawrence, Glenn Miller, et cetera, decided that, having come back to Washington, they wanted to play good music, get a band together.... They approached me to serve as the emcee, advise them on programming.” [35] Since Conover did not play an instrument, the billing for the show read, “Willis Conover presents The Orchestra of Washington, D.C.” [36]

A central arranger for The Orchestra was Bill Potts, who at age 15 had won a talent contest emceed by Conover and sponsored by WWDC. [37] Potts, a pianist and arranger, went on to become known for the 1959 album The Jazz Soul of Porgy and Bess; in the early 1950s, Potts contributed prolifically to The Orchestra’s library of arrangements, including original compositions such as “Playground” and “Willis.” A 2003 Washington City Paper article aptly characterizes Potts’s work as “bold, textured, polyphonic jazz full of nuance and sly humor.” [38] “Playground” is a particularly appropriate example, as a prim, baroque-leaning trumpet introduction seamlessly becomes the melody of a medium/up-tempo blues.

The Orchestra performed at Club Kavakos and hosted numerous guest stars including Dizzy Gillespie (1955), Bud Powell (1953), and Charlie Parker (1953). Bill Potts had the foresight to record many performances, several of which were commercially released decades later: Charlie Parker: The Washington Concerts; Dizzy Gillespie: One Night in Washington; and Bud Powell’s Inner Fires. While the spotlight was on the guest artists, the recordings also provide evidence of the caliber of the band’s performances. Four tape recordings in Conover’s own collection at the University of North Texas expand the known repertoire of the band and feature vocalists Lea Matthews and Jack Maggio.

The band also released its own album, Willis Conover’s House of Sounds: Willis Conover Presents THE Orchestra. “House of Sounds” was a reference to the short story of the same name by M.P. Shiel. [39] Conover again used “House of Sounds” soon thereafter as a program title on WEAM and again at WCBS in the early 1960s, as well as on a later program on the Voice of America for VOA Europe. The album was released on Brunswick, and the notes on the back cover acknowledge the role of producer Bob Thiele in the album’s release. [40]

Further evidence of the depth of Conover’s relationships with jazz musicians resides in Billy Taylor’s “Memories of Spring,” a tune on his 1955 album A Touch of Taylor. Taylor dedicated that tune to Conover, as Bob Altschuler explained on the back of the album cover: “Over the years Billy has received warm encouragement from many of those gentlemen who are customarily identified with microphones and turntables. In this album Billy has tried to answer some of their requests for theme or background music.” [41] Conover was among that select group, which also included Al “Jazzbo” Collins.

Conover’s personal network in radio and in music was formidable, but he still encountered major setbacks. His second marriage was ending; he lost $12,000 in a 1953 concert promotion (equivalent to over $100,000 in 2016), and he lost his sponsor, Ballantine Ale, at WWDC. He was informed his contract would not be renewed, and took a job at WEAM in Arlington, Virginia, which he detested. But it was a conversation he overheard by chance at WEAM that changed his life: the Voice of America was hiring a jazz broadcaster. [42]

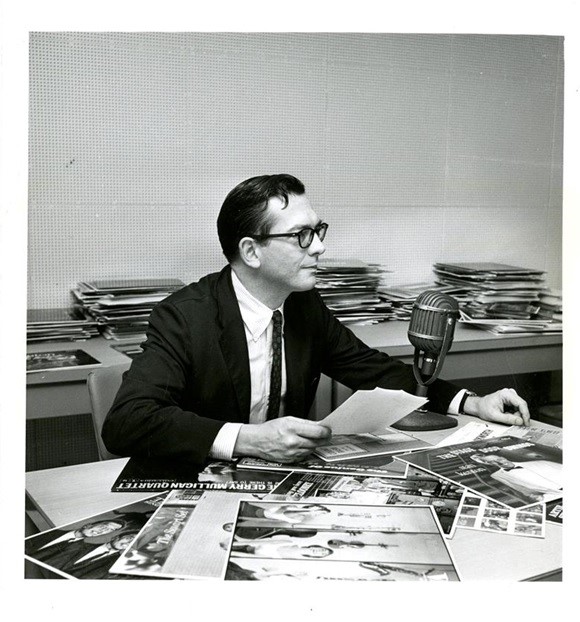

Willis Conover at the Voice of America, circa 1959.

(From the Willis Conover Collection, UNT Music Library.)

He went to the Voice of America only to find that a local sportscaster, Ray Michael, was already signed up to do ninety programs. But it was clear to deputy program manager John Wiggin that Conover not only knew about jazz, but had been an integral part of the Washington, D.C. jazz scene for a decade, and knew the music and the players in addition to his extensive experience in broadcasting. [43] Initially, Conover was hired to cover the program on weekends while Michael did weekdays, but Michael found that Music USA was too much to do five days a week on top of his full-time job elsewhere. [44] Thus, by the spring of 1955, Conover hosted the weekday Music USA programs, which originally featured one hour of popular music and light classics and one hour of jazz. The weekend programs were hosted by Ray Michael for the first few years, followed by local broadcasters Bill Cerri, Paul Norton, and Wayne Hyde through 1961, after which Conover hosted all programs. [45]

The first fourteen months of Music USA programs demonstrate how Conover drew on his unique personal network of access to star power to benefit Voice of America. Most of the guests he interviewed for the Voice of America appeared in concerts he promoted or had appeared on his program on WWDC or WEAM, including Kai Winding [46] (Music USA #131, and #408, with J.J. Johnson), Art Tatum (#172 and #366), Billy Taylor (#181), George Shearing (#219), Louis Armstrong, Barney Bigard, Bobby Hackett, and Woody Herman (#226), Duke Elllington (#300), Charlie Ventura (#302, with Don Elliott), Peggy Lee (#345), Dizzy Gillespie (#358), Stan Kenton (#373), Bob Thiele (#399, with Steve Allen), Billy Eckstine (#420), and Billie Holiday (#447). An unused interview with Johnny Hodges from around February of 1955, possibly a trial run for Music USA interviews, also survives in the UNT Collection. Had Charlie Parker lived past March 12, 1955, it is quite reasonable to expect he would have been on the schedule as well.

It is clear, therefore, that Conover was not trading on the Voice of America name to attract stars to the shows, but rather on his own. This sheds a different light on his status as an independent contractor with the Voice of America. He never transitioned to being a regular employee of the U.S. government. This allowed him to maintain control over the content and quality of his programs and to take on projects outside of the VOA. Music USA would have occurred without Conover under Ray Michael, but it more than likely would have been just another jazz show among the many which occasionally appear and disappear in programming schedules in the U.S. National Archives (with the exception of Leonard Feather’s Jazz Club USA on VOA, which enjoyed a strong run around 1951). A successful program like Conover’s — both musically and diplomatically — required knowledge, enthusiasm, and commitment well above and beyond spinning records. Those attributes made the difference in achieving the goal of forging connections across cultures, as opposed to simply providing long-distance dinner music. Ray Michael and subsequent secondary weekend hosts were fine broadcasters who went on to successful careers in the mid-Atlantic region, but Willis Conover was uniquely suited to take the program to another level. Thankfully, he was afforded the chance to do so.

Bibliography

- “Aircasters,” Broadcasting, January 8, 1951, accessed August 30, 2016, http://www.americanradiohistory.com/hd2/IDX-Business/Magazines/Archive-BC-IDX/51-OCR/1951-01-08-BC-OCR-Page-0048.pdf.

- Breckenridge, Mark. “Sounds for Adventurous Listeners”: Willis Conover, the Voice of America, and the International Reception of Avant-garde Jazz in the 1960s. PhD diss., University of North Texas, 2012.

- “Coast to Coast: District of Columbia,” Radio Daily, November 29, 1946, 8, accessed August 30, 2016, http://www.americanradiohistory.com/hd2/IDX-Business/Magazines/Archive-Radio-Daily-IDX/RD-46/Radio-Daily-1946-Nov-0160.pdf.

- “Conover Traveling,” Washington Post, September 4, 1949, S10.

- Conover, Willis, interview by Billy Taylor, Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Project, August 16–17. 1994.

- Conover, Willis, interview by Clifford Groce, The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project Information Series, August 8, 1989, accessed August 29, 2016, http://www.adst.org/OH%20TOCs/Conover,%20Willis.TOC.pdf.

- Dean, Eddie. “Swing, Or I’ll Kill You,” Washington City Paper, August 8, 2003, accessed August 30, 2016, http://www.washingtoncitypaper.com/news/article/13027274/swing-or-ill-kill-you/.

- “The Duke Ellington Itinerary,” accessed August 29, 2016, http://www.ellingtonweb.ca/Hostedpages/Carl'sRequestedDoojiWebsiteBackups/1941-1950.pdf.

- The Duke Ellington Society, Washington Chapter, “Duke’s Washington,” accessed August 30, 2016, http://www.depanorama.net/desociety/DukesWashington.pdf.

- Ellingtonia, “1941–1951,” accessed August 29, 2016, http://www.ellingtonia.com/discography/1941-1950.html.

- Fosler-Lussier, Danielle. Music in America’s Cold War Diplomacy. Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2015.

- Fritts, Ron. “Charlie Parker at the Washington, D.C. Music Hall,” notes accompanying Charlie Parker — Washington D.C., 1948. Plattsburgh, NY: Uptown Records UPCD 27.55, 2008.

- Harrington, Richard. “THE Orchestra of Jazz,” Washington Post, December 18, 1983, accessed August 30, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/style/1983/12/18/the-orchestra-of-jazz/065d9a73-39ea-4119-bcb9-043e4856784a/.

- Investigation of radio and television programs : hearings before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce ... on H. Res. 278, June 3, 4, 5, 26, September 16, 17, 23, 24, 25, 26, December 3, 4, and 5, 1952, accessed August 30, 2016, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/006765311.

- King, Astrid. “Peg Lynch: Biography,” accessed August 29, 2016, http://www.peglynch.com/biography/.

- Lees, Gene. “The Man Who Won the Cold War: Willis Conover,” Friends Along the Way: A Journey Through Jazz. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2003.

- “‘Morals’ Inquiry: ‘Drys’ Take Offensive as Hearings Begin,” Broadcasting, June 9, 1952, 27, 34, accessed August 30, 2016, http://www.americanradiohistory.com/hd2/IDX-Business/Magazines/Archive-BC-IDX/52-OCR/BC-1952-06-09-OCR-Page-0027.pdf; http://www.americanradiohistory.com/hd2/IDX-Business/Magazines/Archive-BC-IDX/52-OCR/BC-1952-06-09-OCR-Page-0034.pdf.

- Ripmaster, Terence. Willis Conover: Broadcasting Jazz to the World. Lincoln, NE: iUniverse, 2007.

- Sager, Mike. “...Merry-Land Fades Into the Night,” Washington Post, June 24, 1979, accessed August 30, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/1979/06/24/merry-land-fades-into-the-night/2e55b865-b18d-4766-962f-39f13ae25060/.

- Stein, Sonia. “The Jockey’s Got to Know His Steed,” Washington Post, January 27, 1951, B11.

- _____. “That Fatal ‘Slip of a Lip’ Can Sink an Announcer, Too,” Washington Post, March 10, 1946, S8.

- Taylor, Billy. A Touch of Taylor, Prestige Records PRLP 7001, 1955.

- Thomas, Robert McG. “Willis Conover Is Dead at 75; Aimed Jazz at the Soviet Bloc,” New York Times, May 19, 1996, accessed August 31, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/1996/05/19/us/willis-conover-is-dead-at-75-aimed-jazz-at-the-soviet-bloc.html.

- “Today’s Radio Programs,” Washington Post, March 21, 1946, 13.

- Von Eschen, Penny. Satchmo Blows Up the World: Jazz Ambassadors Play the Cold War (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006).

- Weed & Company, advertisement for WWDC, Broadcasting, December 24, 1945, accessed August 29, 2016, http://www.americanradiohistory.com/hd2/IDX-Business/Magazines/Archive-BC-IDX/45-OCR/1945-12-24-BC-OCR-Page-0010.pdf.

- Williamson, Georganne. “On the Town,” Washington Post, October 26, 1949, B13.

- “Willis and Art Make Record,” Washington Post, December 17, 1950, L4.

- Willis Conover Collection, University of North Texas Music Library. http://digital.library.unt.edu/explore/collections/MLCC/

- Willis Conover’s House of Sounds, Brunswick BL54003, 1953.

References

[1] Robert McG. Thomas, “Willis Conover Is Dead at 75; Aimed Jazz at the Soviet Bloc,” New York Times, May 19, 1996, accessed August 31, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/1996/05/19/us/willis-conover-is-dead-at-75-aimed-jazz-at-the-soviet-bloc.html.

[2] Penny Von Eschen, Satchmo Blows Up the World: Jazz Ambassadors Play the Cold War (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006), 14.

[3] Danielle Fosler-Lussier, Music in America’s Cold War Diplomacy (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2015), 85–86.

[4] Gene Lees, “The Man Who Won the Cold War: Willis Conover,” Friends Along the Way: A Journey Through Jazz (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2003), 250–267.

[5] Terence Ripmaster, Willis Conover: Broadcasting Jazz to the World (Lincoln, NE: iUniverse, 2007).

[6] Mark Breckenridge, “Sounds for Adventurous Listeners”: Willis Conover, the Voice of America, and the International Reception of Avant-garde Jazz in the 1960s, (PhD diss., University of North Texas, 2012).

[7] Ron Fritts, “Charlie Parker at the Washington, D.C. Music Hall,” notes accompanying Charlie Parker — Washington D.C., 1948, (Plattsburgh, NY: Uptown Records UPCD 27.55, 2008), 2–25.

[8] Willis Conover, interview by Billy Taylor, Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Project, August 16–17. 1994.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Astrid King, “Peg Lynch: Biography,” accessed August 29, 2016, http://www.peglynch.com/biography/.

[11] Willis Conover, interview by Billy Taylor, Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Project, August 16–17. 1994.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Weed & Company, advertisement for WWDC, Broadcasting, December 24, 1945, accessed August 29,

2016, http://www.americanradiohistory.com/hd2/IDX-Business/Magazines/Archive-BC-IDX/45-OCR/1945-12-24-BC-OCR-Page-0010.pdf.

[14] An earlier version of this article erroneously stated that Conover hosted the WWDC program Melody Lane. In fact, this program was hosted by Mark Austad, an Army friend of Conover’s (Austad was later known as Mark Evans).

[15] Willis Conover Collection, University of North Texas Music Library, Series 2, Sub-Series 4, Box 3, Item 13.

[16] Sonia Stein, “That Fatal ‘Slip of a Lip’ Can Sink an Announcer, Too,” Washington Post, March 10, 1946, S8.

[17] “Today’s Radio Programs,” Washington Post, March 21, 1946, 13.

[18] Willis Conover Collection, University of North Texas Music Library, Series 2, Sub-Series 4, Box 1, Item 8.

[19] The Duke Ellington Society, Washington Chapter, “Duke’s Washington,” accessed August 30, 2016, http://www.depanorama.net/desociety/DukesWashington.pdf.

[20] “Coast to Coast: District of Columbia,” Radio Daily, November 29, 1946, 8, accessed August 30, 2016, http://www.americanradiohistory.com/hd2/IDX-Business/Magazines/Archive-Radio-Daily-IDX/RD-46/Radio-Daily-1946-Nov-0160.pdf.

[21] Willis Conover Collection, University of North Texas Music Library, Series 2, Sub-Series 4, Box 1, Item 10; online at http://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc861621/.

[22] Sonia Stein, “The Jockey’s Got to Know His Steed,” Washington Post, January 27, 1951, B11.

[23] Willis Conover, interview by Billy Taylor, Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Project, August 16–17. 1994.

[24] Ibid, transcribed by author.

[25] Mike Sager, “...Merry-Land Fades Into the Night,” Washington Post, June 24, 1979, accessed August 30, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/1979/06/24/merry-land-fades-into-the-night/2e55b865-b18d-4766-962f-39f13ae25060/.

[26] Georganne Williamson, “On the Town,” Washington Post, October 26, 1949, B13.

[27] Sonia Stein, “The Jockey’s Got to Know His Steed,” Washington Post, January 27, 1951, B11.

[28] “Conover Traveling,” Washington Post, September 4, 1949, S10.

[29] “The Duke Ellington Itinerary,” accessed August 29, 2016, http://www.ellingtonweb.ca/Hostedpages/Carl'sRequestedDoojiWebsiteBackups/1941-1950.pdf.

[30] Ellingtonia, “1941–1951,” accessed August 29, 2016, http://www.ellingtonia.com/discography/1941-1950.html.

[31] “Aircasters,” Broadcasting, January 8, 1951, accessed August 30, 2016, http://www.americanradiohistory.com/hd2/IDX-Business/Magazines/Archive-BC-IDX/51-OCR/1951-01-08-BC-OCR-Page-0048.pdf.

[32] “Willis and Art Make Record,” Washington Post, December 17, 1950, L4.

[33] “‘Morals’ Inquiry: ‘Drys’ Take Offensive as Hearings Begin,” Broadcasting, June 9, 1952, 27, 34, accessed August 30, 2016, http://www.americanradiohistory.com/hd2/IDX-Business/Magazines/Archive-BC-IDX/52-OCR/BC-1952-06-09-OCR-Page-0027.pdf; http://www.americanradiohistory.com/hd2/IDX-Business/Magazines/Archive-BC-IDX/52-OCR/BC-1952-06-09-OCR-Page-0034.pdf.

[34] Investigation of radio and television programs : hearings before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce ... on H. Res. 278, June 3, 4, 5, 26, September 16, 17, 23, 24, 25, 26, December 3, 4, and 5, 1952, accessed August 30, 2016, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/006765311.

[35] Richard Harrington, “THE Orchestra of Jazz,” Washington Post, December 18, 1983, accessed August 30, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/style/1983/12/18/the-orchestra-of-jazz/065d9a73-39ea-4119-bcb9-043e4856784a/.

[36] Willis Conover’s House of Sounds, Brunswick BL54003, 1953.

[37] Eddie Dean, “Swing, Or I’ll Kill You,” Washington City Paper, August 8, 2003, accessed August 30, 2016, http://www.washingtoncitypaper.com/news/article/13027274/swing-or-ill-kill-you/.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Willis Conover, interview by Clifford Groce, The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project Information Series, August 8, 1989, accessed August 29, 2016, http://www.adst.org/OH%20TOCs/Conover,%20Willis.TOC.pdf.

[40] Willis Conover’s House of Sounds, Brunswick BL54003, 1953.

[41] Billy Taylor, A Touch of Taylor, Prestige Records PRLP 7001, 1955.

[42] Willis Conover, interview by Billy Taylor, Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Project, August 16–17. 1994.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Willis Conover, interview by Clifford Groce, The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project Information Series, August 8, 1989, accessed August 29, 2016, http://www.adst.org/OH%20TOCs/Conover,%20Willis.TOC.pdf.

[45] Willis Conover Collection, University of North Texas Music Library, Series 1, Sub-Series 1, Boxes 1–10, 14.

[46] Many of the early interviews may be found online at: http://digital.library.unt.edu/explore/collections/MLCC/browse/?fq=dc_type%3Asound.

Author Information:

Maristella Feustle is the Music Special Collections Librarian at the University of North Texas, and oversees the processing and curation of over 100 special collections in the UNT Music Library. She is the current chair of the Preservation Committee of the Music Library Association and is active as a jazz guitarist in the Dallas-Fort Worth area.

Abstract:

This article examines the portion of the noted radio broadcaster Willis Conover’s career in the 1940s and 1950s when he was active in the Washington, D.C. and Maryland area. His later international successes with the Voice of America are shown to have resulted from earlier local work.

Keywords:

Willis Conover, Washington, D.C., jazz, history

How to cite this article:

- Chicago 15th ed.: Feustle, Maristella. “Willis Conover’s Washington.” Current Research in Jazz 8, (2016).

- MLA 7th ed.: Feustle, Maristella. “Willis Conover’s Washington.” Current Research in Jazz 8 (2016). Web. [date of access]

- APA 6th ed.: Feustle, M. (2016). Willis Conover’s Washington. Current Research in Jazz, 8 Retrieved from http://www.crj-online.org/

For further information, please contact: