Remembering Ed Berger

Michael Fitzgerald

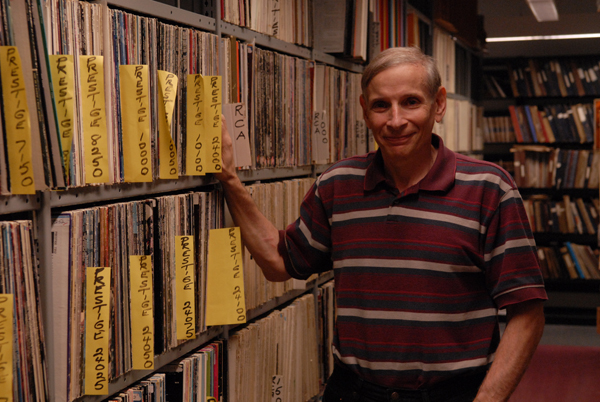

Ed Berger at the Institute of Jazz Studies. Photo courtesy of Larry Berger.

The world of jazz research lost one of its stars on January 22, 2017 when Ed Berger died at home in Princeton, NJ. Son of Morroe Berger, a noted sociologist who specialized in the Near East but who was also a jazz biographer, Edward M. Berger joined the staff of the Institute of Jazz Studies at Rutgers University in 1978. His first publication credit was as a contributor to Charles Nanry’s The Jazz Text in 1979, but he was already collaborating with his father on the landmark book Benny Carter: A Life in American Music, which would be published in 1982, shortly after Morroe Berger’s death. (An updated second edition was published in 2002, just months before Carter’s passing at age 95.) Over the years, Ed Berger worked in a variety of roles with Carter: not only as biographer and discographer, but also as photographer, road manager, record producer, website manager, and even record label co-founder.

Outside of his work on Benny Carter (and his full-time tenured position at Rutgers), Berger wrote or co-wrote important books on jazz figures Teddy Reig (1990), George Duvivier (1993), and Joe Wilder (2014). His photographs were published alongside Gloria Krolak’s poetry as Free Verse and Photos in the Key of Jazz (2015). He was a regular contributor to JazzTimes and served on the editorial team of Journal of Jazz Studies and Annual Review of Jazz Studies.

Although Berger retired as associate director in 2011, he continued to work with IJS as Special Projects Consultant, and the Berger–Carter Jazz Research Fund, which has supported well over a hundred research projects — it was established in 1987 by Benny Carter in memory of Morroe Berger (the Berger family matched the funding and requested that Carter’s name be added to it) — continues.

Over the years, Ed’s influence on jazz scholars was considerable. Here, nine friends and colleagues share their memories of Ed and his contributions to the field of jazz research.

Special thanks to Ken and Larry Berger for photograph permissions.

David Demsey

Ed Berger was a world-class scholar, researcher, photographer, producer, author, administrator, and tireless jazz detective. But all of this is surpassed by his qualities as a person. In his work as an author and photographer, he seemed to gravitate toward subjects who were, like him, quiet giants who shared Ed’s passion for the music and the life.

Two of the best examples of this are the subjects of his two biographies, Benny Carter and Joe Wilder. Ed would throw his hands up and chuckle at the thought that he would ever be thought of as equal to these giants. But in his own way, he was. His book Softly, With Feeling: Joe Wilder and the Breaking of Barriers in American Music was a true labor of love, telling the life story of one of the great people in jazz history and communicating a message of race relations and Wilder’s dogged pursuit of musical equality that had to be told. That was preceded by his two-volume Benny Carter: A Life in American Music (co-authored with Ed’s father and James Patrick), which I present at every opportunity in my university teaching as a paragon of thoroughness and excellence in biographical research. Both books are notable not only because of Ed’s singular writing style, but also because he managed to make them also about the music — a quality too often missing in jazz biographies. It must be noted that Ed’s relationship with these artists became much deeper than that of a biographer. He produced multiple stellar albums for both men, was Carter’s road manager for some time, and made many concert events happen that brought their music to a wider, important audience.

Ed’s musicianship was also apparent in all of his work at the Rutgers Institute of Jazz Studies. Whether he was thinking of the big picture as he navigated campus and grant politics as a ceaseless advocate for the IJS, or quietly helping one of the countless researchers who made the pilgrimage to the IJS doors, his warmth and musicianship always shone through. He treated everyone the same, whether they were a legendary jazz author on a book assignment, or an inexperienced undergrad music appreciation student, trying to discover if someone named Thelonious Monk actually existed. It was always about the magic of this music, and he brought anyone who came into contact with him into that club of people who “get it” — even if they didn’t yet!

I met Ed when I was somewhere between these two levels of expertise, as a young faculty member then at the University of Maine, aspiring to publish my Eastman School of Music doctoral essay on thirds relations in John Coltrane’s music. He welcomed me as a colleague although my inexperience with scholarly article submissions must have shown, and he guided me through the process as he quizzed me about my work, deepening my own knowledge with his questions. When my reviewed draft came back with responses that could only have been made by a few people on the planet, he “broke the rules” by introducing me to reviewer Lewis Porter. Then — there are no coincidences — within a year, when I was appointed Jazz Studies Coordinator at William Paterson University, located twenty-five minutes from the IJS, one of the many great perks was connecting with Ed, Lewis, and the IJS staff regularly in person. As I walked through those wonderful glass doors on every visit, Ed’s face seemed always to be the first one I’d see, with his quiet smile and a twinkle in his eye.

All of us reading this will deeply miss Ed’s unique presence, but in a way I am saddest for all of those future scholars, researchers, writers, and uninitiated students whose lives will never benefit from his warmth, wit, and humanity.

Matthew Snyder

I first visited the Institute of Jazz Studies around 1989 or 1990, in my final year of college, or perhaps immediately following it. One was struck by the magnitude and significance of the place. But even beyond its obvious importance to jazz, I registered, in an almost physical way, that these are archives. These people are archivists. This is what archivists do. Though I cannot remember if I spoke with Ed Berger that day, I later learned of his significance as part of the triumvirate of Morgenstern/Pelote/Berger that created the first golden age of the Institute at Rutgers, an inspiring environment if there ever was one. Ed helped plant the seeds of my career as an archivist, though they would not bloom for another thirteen years.

Ed Berger was dedicated to all the facets and perspectives of jazz historiography: documenting the lives of jazz musicians by photographing and recording them; researching and writing about the music; fostering the careers of scholars; and advancing the careers of archivists interested in working with jazz collections. I experienced Ed from three of those directions.

Queens College, where I received my library/archives degree, requires MLS students to write a master’s research thesis, and, with little clue of what to do, I elected to research the history of general jazz discographies (the works of Rust, Raben, Bruyninckx, Lord, etc.) and investigate the chances for publication of a modern, well-researched version of those works. The details of my research project are not worth recounting, but Ed, who generously agreed to read the thesis before its submission, saw value in it because it more-or-less described the current state of the field at that time (2004). To my shock, he encouraged me to edit and pursue publication of the thesis in the Annual Review of Jazz Studies. Me? Publish jazz research? I was just about to graduate with my MLS and commence my career as an archivist at The New York Public Library; I wanted to assist researchers, not do research myself. But I understood later that Ed saw in me yet another budding scholar whose work should be encouraged. His advice was perhaps more than I deserved: despite his best efforts, and to my now-eternal regret, I did not follow up on it.

For many years, I saw Ed at the occasional IJS jazz research roundtable (I recently presented for the first time at a roundtable on the career of George Avakian, an event I am sad Ed did not live to see). But the most professionally rewarding experience I had with him began soon after he helped create the IJS’s Jazz Archives Fellowship program in 2012, which aims to help develop the careers of jazz archivists, as well as increase the diversity of the field. Once or twice a year, he brought that semester’s current crop of aspiring archivist fellows on a tour of music repositories in the New York metropolitan area, including my own place of work, to watch, listen, learn, discuss, and ask questions of me and the other archivists at NYPL. Over time, after I gave my spiel and witnessed Ed taking obvious pride in his mentees, I gained a new appreciation for the good work he was doing.

(l–r) The author and Perry Robinson at Sweet Rhythm, 2007.

Photo © Ed Berger.

Archivists are trained to approach collections from all types of creators, in any subject specialty; we are assumed, for the most part, to be able to assess and describe collections without an absolute need for expertise in their creator’s life or work. But I envy the experience those IJS fellows have had in Ed’s program, learning the ropes from a man so deeply immersed in jazz and its documentation. He combined personal, almost familial relationships with musicians with the mindset of a documentarian, the skills of a librarian and archivist, and the perspective of a scholar who had worked in all those roles. Today, subject specialties are out of style in the library world, but Ed was living proof of what they bring to the table.

My most personal experience with Ed Berger, however, was having the unique experience of being photographed by him. In 2007, I was playing alongside the clarinetist Perry Robinson at a benefit for pianist Eli Yamin at Sweet Rhythm in Greenwich Village, and Ed’s portrait of me with Perry (one of my musical mentors) is a precious artifact made even more poignant now that Ed is gone. It is one thing to observe that Ed, on top of his other accomplishments, was one of the great practitioners of jazz photography. It is quite another to be one of his subjects, recognizing that this man, who had documented towering musicians like Benny Carter, Joe Wilder, and so many others, thought the moment important enough to preserve. In retrospect, it is one of the highest honors of my life.

Peter Pullman

I met Ed when IJS was still in Bradley Hall. In my early visits there, I was too in awe of Dan Morgenstern to talk to him. But I had no trouble finding things to ask Ed and Vince Pelote. Maybe that they were about my age was the reason.

I got to know Ed well in the late 1990s, when I asked for his help in learning about Teddy Reig, who was thought to have been present at what discographies have long claimed was Bud Powell’s first studio record date as a leader. I had read Ed’s book on Reig but, in checking its facts, a number of problems posed themselves. Reig was dead by this time, so I asked Ed if he would lend me the tapes of his interviews. Ed did not hesitate, getting me the two cassettes that contained Reig’s remarks about Powell.

Reig had told Ed a long, colorful story about organizing Powell, Curly Russell, and Max Roach for the record session; arranging their travel to an obscure New Jersey studio; how the music went down; and what happened to the discs afterward. But after interviewing Jack Hooke twice over the next couple of years, I judged him to have run the session and Reig not to have been present in that studio at all.

I shared my findings with Ed. I told him further that Reig must have been responsible for discographies dating Powell’s session as having taken place in January 1947, [1] which “fact” led to a major misunderstanding in jazz history: that Powell (b. 1924) had recorded as a leader nine months earlier than had his mentor, Thelonious Monk (b. 1917). The truth: Monk recorded under his own name more than sixteen months before Powell had. Monk had completed four sessions by the time (summer 1949) of the Powell record date that Hooke and Reig were responsible for.

Ed might not have known what I would make of his Reig materials. He did not react much when I all but accused him of having put in print, without vetting, his subject’s verbatim account. (I also questioned Ed’s discography for Reig, which included sessions that Reig had not produced — ones that he had not paid for but said he had been merely present at.)

The issue between us came to the fore when Ed peer-reviewed a draft of my manuscript. I knew that he would be harshly critical; that is why I had wanted him to read it. The other peer-reviewer was a musicologist, but it was Ed who pointed out where I had used incorrect music terminology. He did, though, praise the work’s thoroughness in evaluating sources and quotient of original research. He did not say anything about my debunking of Reig.

Now that my book has been released, a divide in our discipline has become plain to me. There are as-told-to accounts of living artists, and there are historical biographies. The former provides the latter with a foundation, on which to build or beneath which to excavate (or, even, tear down). There is room for both kinds of works.

Ed was tireless in doing all that he could to provide researchers with the tools that they needed. But it was his reticence where deeper research undermined his own findings that was the mark of Ed’s true selflessness.

[1] It was common practice to backdate a session that took place while the artist was under contract to another company. Discographers have an obligation, then, to dig deeper when aspiring to accuracy in their work.

Fernando Ortiz de Urbina

As codified as jazz scholarship may have become as it has entered academia, M.A. and Ph.D. candidates will still get a rush of adrenaline when they meet a legendary musician, find a coveted record, listen to an unissued track, or, in all our glorious nerdism, step into a distant archive.

Try to picture the foreign scholar (with varying degrees of command of the English language) in the United States — the birthplace of jazz — visiting the Institute of Jazz Studies in New Jersey. Objects seen in pictures or heard about become tangible; names read in the best available literature are suddenly real. This could well lead to a Stendhal moment were it not for the unassuming, welcoming spirit of the Institute, part of which was of Ed Berger’s making.

When I met him at the Institute back in 2012, the slender and hoodie-wearing Ed looked more like a phys. ed. instructor than the associate director of such hallowed grounds. Before that, we had had some email exchanges, the first of which regarded some research he had done: typically, as I would learn later, he deemed it more brief than useful, and ended with, “Let me know if I can be of any further assistance.” He could and he was.

Our exchanges were mostly about the darker corners of jazz discography: he would send lists of non-jazz sessions which included Eddie Costa, and I would reciprocate with recordings featuring Joe Wilder, the subject of his last biography, be it salsa (Tito Puente) or calypso (Harry Belafonte’s guitarist Millard Thomas). My numerous queries to identify musicians in old photographs never went unanswered, and he would show them to anyone he thought might help.

My fellow countryman Juan Zagalaz spent three months of his Ph.D. studies at the Institute in 2009. He remembers his humility: “I would be talking to Dan Morgenstern, and Ed would interject from the other end of the room. He would say ‘I don’t think I could add much more to what Dan has told you,’ and then he would always add something.”

Ed’s generosity — he never left any of my emails without reply, “We’ve been swamped” being a regular apology — and modesty, his lack of interest for the spotlight, may explain his keen eye of photography, of which work he uploaded almost 10,000 images to his Flickr account (https://www.flickr.com/photos/eebeephoto/albums), possibly the largest jazz photography collection by a single author, for all to peruse.

Readers of this note will — or most certainly should — know Ed’s trio of biographies: those of Teddy Reig, George Duvivier, and Joe Wilder (Ed’s work on Benny Carter was done as co-author). He was a friend of all three subjects, and all three benefited from the way he managed the spotlight. His rapport with two such gentlemen as Duvivier and Wilder should surprise no one. Ed’s true achievement as a biographer, given their difference in backgrounds and temperament, is his book with Teddy Reig. Bob Porter, who witnessed their exchanges, observed, “They were absolute opposites...the librarian and the hustler, strange bedfellows but good friends.” Indeed, Ed managed to make the book an accurate hoot.

For his work in jazz scholarship, Ed was much more important that he cared to let people know. When his colleague at the Institute Annie Kuebler died, he wrote in an email: “I’m not sure that we truly comprehended until now just how deeply she touched the lives of so many in the jazz community.”

The same goes for Ed.

Jeff Sultanof

It was Bill Kirchner who introduced me to Ed back in the 1990s, one of many he has introduced me to who have become colleagues and friends. I had been working for Warner Bros. Music Publications, and the company frowned on any of us getting involved in professional organizations or making ourselves known at places such as the Institute of Jazz Studies or the Library of Congress. When I left Warner Bros. in 1994, Bill told me about the IJS roundtables, and I began attending them, meeting many of those who regularly presented and attended at the time. James Maher, Michael Fitzgerald, Lewis Porter, Joshua Berrett, and William Bauer got to know me and hear about my background and historical work, which were not widely known at the time. I began writing articles and doing advanced research, and Dan Morgenstern, Vincent Pelote, John Clement, and of course Ed, became colleagues and friends. Later we were joined by the amazing Annie Kuebler.

I had already known of Ed because of his two-volume masterpiece, Benny Carter: A Life in American Music. I asked him a lot of questions about it and enjoyed his off-beat sense of humor and his love of anything Benny. Benny had long been a hero of mine, and I had many of his recordings. Whenever I would go to IJS, Ed and I usually talked at length. Sometimes we were joined by Vincent, and I sat back as they comically insulted each other.

When I worked as an editor at Hal Leonard Publications in 1995, a Carter solo transcription book was being prepared. “I’ve told Benny about you, and he wants you to work on it,” Ed said. I told him that I did not think they would pull another editor off of the book so that this could happen. “You’ll work on the next one,” Ed said. He had high hopes for the Hal Leonard connection, which he hoped would include the company publishing Benny’s many compositions and arrangements. As it turned out, Hal Leonard did another book with Benny that I did edit, but they showed no interest in publishing his big band work. Some years later, Benny and Ed were trying to get Hal Leonard to publish a Carter fakebook, and once again, Benny asked for me.

Ed’s devotion to Benny often caused his colleagues to smile. The joke (perpetuated by Pelote) was that whatever the subject being discussed at IJS or at a roundtable presentation, Ed would find some excuse to tie Benny and/or his work into it. I cannot remember the occasion exactly, but he did bring up Benny in an esoteric way during one such presentation, and both Vinnie and I started giggling, totally confusing Ed. Vinnie did tell Ed about it the day afterward.

I was in Sherman Oaks for New Year’s in 1999 when I got a phone call to go see Benny; Ed apparently told him I was in town and should help him out with his copyrights. My visit with Benny is something for another time, but I will never forget that Ed made that meeting happen. One never takes for granted visiting and helping a giant in American music. Those of us who are passionate about music know what it is like to be among the legends who fostered our love of the music in the first place.

Eventually Sierra Music began publishing some of Benny’s big band music, particularly the Kansas City Suite written for Count Basie, but Ed wanted a lot more of Carter’s music out. At that point, I had become the editor at Jazz Lines Publications, and Rob DuBoff jumped at the chance to publish Carter. At that point, Benny had passed, but Ed and Benny’s widow, Hilma, had the satisfaction of seeing Carter’s compositions become some of the biggest sellers in the Jazz Lines catalog. I have always been proud to have given Ed that gift of further perpetuating Carter’s great musical gifts. As I said in an article about Benny, his music was reaching the audience that perhaps appreciated him most — high school and college students — as his music was great to play and made even mediocre ensembles sound good.

As we know, Ed was always carrying his camera when he went to a concert or convention — he and Joe Wilder were always welcome sights wherever they went. So naturally when I needed some photos taken, I asked Ed. He took them gratis, and they are marvelous, of course — the best photos of me ever taken. I look at them and think of Ed, but Ed has touched me in so many ways, I wind up thinking of him often. His spirit is very much in evidence at IJS, and I feel his presence when I go there. He left a very special mark in American music, and it was a blessing to have known him.

Bill Kirchner

My recollections of Ed Berger, with whom I enjoyed a friendship going back almost forty years, cover a wide variety of subjects — ranging from the laughably trivial to the profound. For those of us who knew him well, Ed was first and foremost a friend — one who could always be depended on.

Central to Ed’s life was his close relationship with Benny and Hilma Carter. In fact, it was in that capacity that I first met Ed in the late 1970s when I was working for Time–Life Records on a Benny Carter Giants of Jazz boxed set of recordings. In later years, as I developed a friendship with Benny and Hilma, I inevitably developed one with Ed as well. After Benny’s death in 2003, Ed and I collaborated on producing a memorial for Benny at St. Peter’s Church in New York City. As this listing of participants (taken from my online discography) shows, it was quite an evening — one that all of us who participated were honored to be part of.

Date: September 15, 2003

Location: St. Peter's Church, New York City

Label: [private recording]

Bill Kirchner (ss), Jerry Dodgion, Jon Gordon, Brad Leali, Mark Vinci, Steve Wilson (as), Daniel Block, Mike Campagna, Jimmy Heath, Jack Stuckey, Frank Wess (ts), Loren Schoenberg (ts, con), Carl Maraghi (bar), Seneca Black, John Eckert, Wynton Marsalis, Mike Rodriguez, Randy Sandke, Jumaane Smith (t), Clark Terry, Joe Wilder (fh), Eddie Bert, Mike Christianson, Ronald Westray (tb), Howard Alden, James Chirillo, Russell Malone (g), Kenny Barron, Ray Bryant, Bill Charlap, Dick Katz, Chris Neville, James Williams, Richard Wyands (p), Daryl Sherman (p, v), Lisle Atkinson, Steve LaSpina (b), Jason Brown, Steve Johns, Kenny Washington (d), Joe Kennedy, Jr. (vn), Roberta Gambarini, Barbara Lea (v)

| a. | 01 | The Blessing(Benny Carter) |

| b. | 02 | Key Largo(Benny Carter, Karl Suessdorf, Leah Worth) |

| c. | 03 | A Walkin' Thing(Benny Carter) / arr: Bill Kirchner |

| d. | 04 | Sunday Morning(Benny Carter) |

| e. | 05 | I'm In the Mood For Swing(Benny Carter) |

| f. | 06 | When Lights Are Low(Benny Carter, Spencer Williams) |

| g. | 07 | Cow Cow Boogie(Benny Carter, Don Raye, Gene DePaul) |

| h. | 08 | I'm Coming, Virginia(Will Marion Cook, Donald Heywood) / arr: Benny Carter |

| i. | 09 | Other Times(Benny Carter) |

| j. | 10 | All About You(Benny Carter) |

| k. | 11 | People Time(Benny Carter) |

| l. | 12 | The Courtship(Benny Carter) |

| m. | 13 | I Was Wrong(Benny Carter) |

| n. | 14 | Only Trust Your Heart(Benny Carter, Sammy Cahn) / arr: Mark Lopeman |

| o. | 15 | Symphony In Riffs(Benny Carter) / arr: Benny Carter |

| p. | 16 | Souvenir(Benny Carter) |

Bill Kirchner (ss) on c; Jerry Dodgion (as) on h; Jon Gordon (as) on n-o; Brad Leali (as) on h; Mark Vinci (as) on c; Steve Wilson (as) on n-o; Daniel Block (ts) on h; Mike Campagna (ts) on n-o; Jimmy Heath (ts) on b-c; Loren Schoenberg (ts) on n-o, (con) on n-o; Jack Stuckey (ts) on n-o; Frank Wess (ts) on h; Carl Maraghi (bar) on n-o; Seneca Black (t) on n-o; John Eckert (t) on n-o; Wynton Marsalis (t) on i; Mike Rodriguez (t) on n-o; Randy Sandke (t) on e; Jumaane Smith (t) on n-o; Clark Terry (fh) on l; Joe Wilder (fh) on a; Eddie Bert (tb) on n-o; Mike Christianson (tb) on n-o; Ronald Westray (tb) on n-o; Howard Alden (g) on h; James Chirillo (g) on n-o; Russell Malone (g) on j; Kenny Barron (p) on k-l; Ray Bryant (p) on g; Bill Charlap (p) on p; Dick Katz (p) on n-o; Chris Neville (p) on d-f, i; Daryl Sherman (p) on m, (v) on m; James Williams (p) on a; Richard Wyands (p) on b-c, h; Lisle Atkinson (b) on b-c; Steve LaSpina (b) on e-f, h-i, l, n-o; Jason Brown (d) on n-o; Steve Johns (d) on e-f, i, l; Kenny Washington (d) on b-c, h; Joe Kennedy, Jr. (vn) on a; Roberta Gambarini (v) on f; Barbara Lea (v) on n.

Videotape exists of this Benny Carter Memorial Tribute coordinated by Ed Berger and Bill Kirchner.

Ed Berger was master of ceremonies. Spoken comments by Pastor Carol Fryer and Berger precede a. Comments by Bill Kirchner precede c. Comments by Dan Morgenstern precede g. Comments by Stanley Crouch precede i. Comments by Phil Schaap precede m. Comments by Gary Giddins precede n.

Ed’s close relationship with Benny led to a project that outlived Benny: the Evening Star record label. As was stated on the label’s website: “The Evening Star label was founded in 1992 by Ed Berger of the Institute of Jazz Studies of Rutgers University, with the assistance of Benny Carter. Evening Star is an independent label featuring jazz artists who have been overlooked by the major companies, new talent, and occasional special historical issues.” Among the artists involved were Joe Wilder, Chris Neville, Benny Carter and Phil Woods, Randy Sandke, Ray Bryant, singer-lyricist Deborah Pearl, and myself, as well as a multi-artist Benny Carter Centennial Project. Ed became a one-man record label with CDs stored in boxes in his apartment. He approached this role with typically self-deprecating good humor.

Last, I’d like to mention Ed’s major gifts as a photographer — they went back to the 1960s, when he shot a remarkable photo of Louis Armstrong. Not long before Ed died, a book of his photos and Gloria Krolak’s verses — Free Verse and Photos in the Key of Jazz — was published. I’m honored to be included in this book. As one who finds it impossible to pose for photographers, I can say that the candid action shots Ed did of me over several years are my favorites. As with everything else he did, Ed put himself in the background. That made his unique gifts all the more apparent.

Janice Greenberg

From 2002 to 2010, I worked very closely with Ed Berger — writing, rewriting, correcting, and reformatting my manuscript for Jazz Books in the 1990s: An Annotated Bibliography, which was to be part of the Studies in Jazz series from the Institute of Jazz Studies. I quickly learned to trust Ed’s judgment implicitly (although occasionally I stubbornly disagreed and firmly held my ground). We had a mutual respect for each other which grew as my work on the book slowly progressed.

I knew from the start that I would have my work cut out for me, because Ed had shown me a book review that he had written for the Annual Review of Jazz Studies on the revised edition of a bibliography in which he called out the first edition as an “unmitigated disaster.” He continued, “Poor organization, misleading annotations, omissions, rampant misspellings, and haphazard indexing rendered it virtually useless.” The second edition, according to Ed, “is vastly expanded, but I’m sorry to say, offers only marginal improvements in the aforementioned areas, and remains greatly flawed.”

Looking through the countless emails that Ed sent me over those years, I see his continuous concerns for consistency and accuracy. He wanted the best from me and knew that I could deliver it. His meticulous eye for detail, whether it be in catching misspellings (foreword was a frequent culprit), punctuation errors, stylistic improvements, or better placement of an entry, helped make my book the high quality work we both desired and a worthy volume in the series.

Ed knew what to say to calm my nerves as I dealt with deadlines, formatting difficulties, and making all of the necessary changes that were required. His patience and firm guidance in his stewardship meant more to me than I could adequately say in words, although I did thank him numerous times. Below are some of his comments:

“Overall you’ve done a great job and it represents a lot of work. That said, there are many minor corrections that need to be made before it is ready for ‘prime time.’”

“Don’t get discouraged!”

“Overall it looks much improved.”

“It looks like you’re almost there. Good work.”

Occasionally, though, his dry humor got the best of him. When my editor, Renee Camus asked him where he thought that a book on skiffle players should belong he replied, “I guess General History would be the most likely choice. (Or the trash? — Sorry!)”

Ed helped my manuscript develop clarity and consistency. He was always able to find a better word. If he did not know the answer to my question, he would say “Go ask Dan.” There was no ego involved. Ed was a very intelligent but extremely humble man.

My biggest challenge was formatting the manuscript so it could be camera-ready. It was extremely frustrating and overwhelming for me that the text would not lie properly on the pages. Ed was very encouraging and empathic. Finally, he wrote me that he would look at a “problematic” sample section. With Ed’s help I finally overcame that obstacle.

Ed’s trust in me, along with Dan’s, to carry through this challenging project meant a lot to me. As I neared the end of revising my manuscript, I found myself increasingly anxious and vulnerable. Ed was very good at calming the nerves of this novice book author.

In the dedication to my book, I called Ed “my friend, mentor, and editor.” In my acknowledgments, I wrote, “I am very fortunate to turn to Ed Berger for guidance. In matters of writing style and jazz information, he is a fount of knowledge and has a gift for making it look good on paper.”

Ed’s foreword to my book is something that I will always treasure. In the last paragraph he wrote:

Janice Greenberg has leapt into the breach with this first volume of a projected decade-by-decade examination of the jazz literature. My colleagues and I at the Institute of Jazz Studies witnessed first-hand the dedication and tenacity Janice brought to this project as she relentlessly pursued every lead in a venture where “the devil is in the details.” Dan Morgenstern, my series co-editor, once wrote an article in Down Beat with the title “Discography: The Thankless Science.” Surely, bibliography is an equally thankless task. This volume is an important first step that will benefit jazz researchers for years to come.

My book was published in March 2010 by Scarecrow Press, as No. 61 in the Studies in Jazz series. When the reviews came out, I rejoiced with Ed over the praise and positive comments. Then one reviewer found fault with my approach to the book. I was devastated. After reading the review, Ed calmly pointed out that the reviewer was looking forward to my next bibliography in this series.

For the past seven years, I have been doing research on another book on jazz. When I showed my first chapter to Ed last year, I felt like a student waiting for her evaluation from her professor. Ed said that basically it looked good but there were several improvements that he suggested that I make. Some months passed, and I was almost ready to resubmit my revised work to Ed when I received the phone call that he had passed away.

It has been hard for me, as it has for so many of his colleagues, family and friends, to fathom that there will no longer be Ed in our lives. From our relationship as writer and editor, there developed a strong friendship. I consider myself very lucky to have been called by Ed, a “good friend.” I definitely feel the same way.

Scott Wenzel

I first met Ed Berger probably in the early to mid-1990s at the Institute of Jazz Studies when I began researching and then producing sets for Mosaic Records. I cannot count on my fingers the number of times Ed would corral me into his or Vinnie Pelote’s office to listen to a Carter solo he wanted to share. Before my visits to the IJS I had known of Ed through his outstanding discographical work and love of Benny but never knew him personally. He was always asking Michael Cuscuna and me when we were going to issue a Benny Carter set on Mosaic. This would usually get a sarcastic response something to the effect of: “Sorry, Ed, but our next release will be The Complete Decca Solo Recordings of Carmen Lombardo.”

The author at the Jazz Collectors Bash, 2014. Photo © Ed Berger.

That sense of humor and sarcasm was something that Ed also possessed. I think Ed and I (along with Loren Schoenberg and other friends of Ed, I am sure) could recite quotes from various episodes of The Honeymooners. His love of that iconic television program was on display in his office where there was a picture of the Kramden’s living room and a Photoshopped headshot of Ed peering in from the window. Brilliant!

A highlight for me each year comes in June when the annual Jazz Record Collectors’ Bash is held in New Jersey. There was a stretch of time when Ed did not show up for whatever reason. However, I guess it was in the last five years or so when both Vinnie Pelote and Ed would grace us with their presences. In 2014, Ed, always with his camera on hand, came by our Mosaic table and we started chit-chatting and poking fun at all the record nerds (of which we were certainly a part). About a week later Ed emailed a picture he had taken of me and a “Potato Head” Whiteman 78. He wrote in the email accompanying the photo (and inserting a Honeymooner-ism) “Of you holding a rare Paul Whiteman release on the KRANMAR label. Note recently deceased collector at left. I wasn’t joking when I suggested they have medical personnel to regularly check pulses of the attendees.” The best part of this was when I emailed my mom and dad this picture along with Ed’s comment. My mom immediately called me and said, “Oh my God...someone died at the Record Bash?!”

Ed was always helpful with whatever Michael or I needed from the Institute. Because of his help in our set of Classic Capitol Jazz Sessions (for which Dan Morgenstern wrote his usual insightful notes) I had a call one day from Benny Carter saying how much he loved and appreciated the fact we had released all of his Capitol sessions during the 1940s (“Prelude to a Kiss” is a desert island disc for me.) It is a phone call that I will always remember with awe.

I miss Ed. His humor. His passion. His love of music and of life. Baby...you were the greatest.

Randy Sandke

Ed Berger kindly wrote the foreword to my book, Where the Dark and the Light Folks Meet, and he begins it with our meeting as freshmen at Indiana University in 1966. I was drawn to his room by sublime sounds wafting through the drab hallway at Wright Quad where we both lived. I knocked on the door and was welcomed in by someone destined to become one of my closest and most enduring friends.

We sat and listened to an entire album: the classic collaboration of Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington from 1961. I especially recall the closing track, Ellington’s haunting ballad “Azalea”, sung as only Armstrong could render it. The lyric was written by Duke himself and is a gem, rhyming “church-like pomp” with “cypress swamp”; and “regalia,” “nothing evil can assail you,” and “with you who could be a failure” with “Azalea.” Genius and more genius, and all thanks to Ed for sharing it with me.

But he was not through yet. Ed put on a Benny Carter record and encouraged me to soak in more brilliance: not only the wit and supple elegance of Carter’s alto playing, but his astounding trumpet solos — all of which were new to me.

In later years Ed introduced me to the man himself. Carter had been a long-time family friend, and Ed, along with his father, Morroe, and James Patrick, wrote the definitive biography of the master: Benny Carter: A Life in American Music. I noticed immediately that Carter’s personality was much like Ed’s; the effortless charm, deep but unostentatious knowledge, self-deprecating humor, subtlety, reserve, and the ability to surprise you with stunning and unexpected revelations.

Ed taught me so much, and was always there when I needed advice or assistance. For starters, I got a lot of mileage out of “Azalea”. I ended up recording it twice: once for orchestra and another time as a duet with guitarist Howard Alden. I also arranged it for the Carnegie Hall Jazz Band.

When George Wein wanted to produce a concert in honor of Sidney Bechet with the Carnegie band and asked me to arrange pieces of my choosing, Ed suggested I listen to Bechet’s two long-form suites: La Colline Du Delta and La Nuit Est Un Sorcière. I selected the first, and conducted it in what turned out to be its American premiere, a full half-century after its Paris debut. Thank you, Ed.

The number of favors Ed did for me is almost endless. He wrote liner notes for recordings, showed up at concerts and record dates with camera in hand (beside jazz, photography was his other main passion), edited and fact-checked my writing, gave me entrees to all sorts of people in the jazz world, and on and on. Two brief instances stand out. For my album Trumpet After Dark, Ed took some beautiful photos of the viola da gamba consort plus Bill Charlap, Greg Cohen, and Dennis Mackrel. Afterwards Ed and I ventured onto the fire escape outside of Nola Studios, sixteen stories above the streets of Manhattan. There he performed death-defying contortions to get the right shot of me with the New York skyline in the background — just a typical night’s work for Ed, and all after turning in a full and exhausting day at the Institute of Jazz Studies. Another time, Ed and I met around Cooper Union to take photos for The Subway Ballet. This involved sidestepping hordes of people rushing toward him in order to photograph the exterior and interior of the subway station, as well as running in and out of subway cars. Fortunately, we both survived, and the results, as always, were superb.

The author’s cat, Julius. Photo © Ed Berger.

Among my most treasured possessions are photos Ed took when my wife, Karen, and I would have Ed over for dinner. He always brought his camera. Over the years, Ed took series after series of photos of our son, Bix. There is Bix in all his glory: smiling, laughing uncontrollably, playing with toys, eating, on the verge of a tantrum, or simply staring back quizzically at Ed. Like a great jazz musician, Ed captured the moment for all time.

He was wonderful with kids and loved his nephews as if they were his own sons. Photos of them lined his office. Ed definitely had some Rembrandt in him — the gift to reveal the soul behind the expression. I see this in his portrait of my late and beloved cat Julius, which he gave me as a life-size print. The clarity and detail is astonishing, but most of all, the beauty of Julius’s personality is rendered visible. How did Ed do it? I do not know, but he did.

When I sadly informed saxophonist and mutual friend Scott Robinson that Ed was gone, Scott reflexively said, “What a sweet and selfless guy.” How true. Ed was always doing things for others, and rarely seemed to give a thought to himself. Maybe that is why so many people loved him, valued his many talents, and depended on his wisdom, knowledge, and insight. And again, like a great and original jazz artist, no one can replace him.

Love you, Ed. You’ll always be part of my life.

Author Information:

David Demsey is Jazz Studies Coordinator and Living Jazz Archives Curator at William Paterson University. His book John Coltrane Plays Giant Steps (Hal Leonard) is widely known. He published two books on composer Alec Wilder, and his “Improvisation and Concepts of Virtuosity” is the final essay in The Oxford Companion to Jazz. A longtime Saxophone Journal contributing editor, his articles have also appeared in Down Beat, Instrumentalist, Jazz Educators Journal, and Journal of Jazz Studies, and he wrote liner notes for five Verve Records CDs. As a saxophonist, Demsey has appeared with trumpeters Clark Terry and Randy Brecker, pianists Mulgrew Miller, James Williams, Bill Charlap, and Jim McNeely, with the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra since 1999, and he has performed with the New York Philharmonic since 1994 including an all-Gershwin recording and two world tours. His graduate degrees are from Eastman School of Music and the Juilliard School, and he is a Selmer Saxophone Clinician.

Janice Leslie Hochstat Greenberg is senior librarian at the Technical Services Department of the Jersey City Free Public Library. She is the author of Jazz Books in the 1990s: An Annotated Bibliography (Scarecrow, 2010). She is also a contributor of the volume Library Services to Youth of Hispanic Heritage, Immroth, McCook, Jasper eds. (McFarland, 2000). She is currently working on a book on early jazz piano.

Bill Kirchner is a composer-arranger, saxophonist, bandleader, record and radio producer, jazz historian, and educator. He has toured worldwide as a soloist/clinician and has recorded nine albums as a leader. His latest CD releases are Lifeline (with his Nonet), One Starry Night (with his Nonet and guest vocalist Sheila Jordan), Old Friends (duo with pianist Marc Copland), and An Evening of Indigos, all for the Jazzheads label. Kirchner has received Grammy, NAIRD Indie, and Jazz Journalists Association awards. He is the editor of The Oxford Companion to Jazz and A Miles Davis Reader and teaches in the jazz programs at The New School and Manhattan School of Music. He produced and wrote four one-hour “Jazz Profiles” for National Public Radio, and he hosted 131 one-hour shows on WBGO-FM as part of the “Jazz From The Archives” series. Kirchner’s website is http://www.jazzsuite.com.

Fernando Ortiz de Urbina has written about music since 1993 in several Spanish and British newspapers and magazines, including Cuadernos de Jazz and Jazzwise. He currently runs a bilingual blog (https://jazzontherecord.blogspot.com) and has regular slots in the Spanish-language jazz podcast El Club de Jazz.

Peter Pullman was the first US correspondent for Wire (UK), when it was devoted to jazz coverage. He then worked for seven years with the Verve label’s classic-jazz repertoire, helping to prepare it for release on CD. After his Grammy nomination for liner notes, for The Complete Bud Powell on Verve, he undertook to write the great pianist’s biography. Wail: The Life of Bud Powell was issued in December 2012 (Brooklyn: Bop Changes).

Randy Sandke has been known as a jazz trumpeter since the early 1980s. He has toured extensively both in the United States and abroad and has recorded over thirty albums as a leader. He has also composed much original music, including several long-form pieces such as The Subway Ballet, Symphony for Six, and The Mystic Trumpeter. Sandke has also written articles for The Oxford Companion to Jazz and Annual Review of Jazz Studies, plus two books: Harmony for a New Millennium and Where the Dark and the Light Folks Meet. He lives in Pennsylvania with his wife, son, and two cats.

Matthew Snyder is a music archivist who has been processing special collections at The New York Public Library since 2004. From 2004 to 2006, he was the personal archivist for the producer George Avakian. After the 2013 acquisition of the George Avakian/Anahid Ajemian papers and recordings by NYPL, he processed the collection and curated the exhibition Music For Moderns: The Partnership of George Avakian and Anahid Ajemian at The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, in 2016. Mr. Snyder was the founding chair of the Music Library Association’s Archives and Special Collections Committee, and is a member of the MLA Working Group on Archival Description of Music Materials. A working clarinetist and saxophonist, he received his master of library and information studies from Queens College, City University of New York; a master of music in jazz studies from the Indiana University School of Music; and a bachelor of arts in music from Rutgers College, New Brunswick, NJ.

Jeff Sultanof is a composer/arranger/conductor who is a pioneering editor of American historical big band and concert music. He was editorial director at Warner Bros. Publications, where he edited the music of John Williams, George Gershwin (including facsimile editions of Gershwin scores), Cole Porter, Max Steiner, and Alex North, among others. His compositions and arrangements have been played by student and professional ensembles all over the world. He has produced educational recordings by Gerry Mulligan, Andy LaVerne, and Ron Carter, and has written for the Journal of Jazz Studies, jazz.com and the blogs rifftides and do the math. Currently he is the administrator of the music business program at the Institute of Audio Research as well as editor at Jazz Lines Publications.

Scott Wenzel (b. 1960) started collecting 78s while still in grammar school. He studied reeds throughout high school (chosen for the NYS High School Jazz Ensemble) and majored in Communications and Music while at Towson State University (Maryland) where he hosted a number of jazz programs over WCVT-FM. After graduation he joined jazz station WYRS-FM in Stamford, CT. In 1987, Wenzel joined Mosaic Records as a warehouse manager. In 1999, owners Charlie Lourie and Michael Cuscuna called upon Wenzel to become a producer. In this role he is a three-time Grammy Award nominee in the Best Historical Issue category and winner at the Jazz Journalist Association awards. He has also produced CDs and supplied 78s for Sony Legacy, Blue Note, and Capitol. He was one of the consultants on the PBS documentary Ken Burns Jazz and has written liner notes for various jazz CDs. Wenzel also leads a 16-piece swing band and a jazz trio in the Westchester, NY area.

Abstract:

Nine friends and colleagues remember the late Ed Berger, jazz biographer, discographer, photographer, record producer, and former associate director of the Institute of Jazz Studies at Rutgers University.

Keywords:

Ed Berger, memorial, jazz, archives, photographs, discography, history

How to cite this article:

- Chicago 15th ed.: Fitzgerald, Michael, David Demsey, Matthew Snyder, Peter Pullman, Fernando Ortiz de Urbina, Jeff Sultanof, Bill Kirchner, Janice Greenberg, Scott Wenzel, Randy Sandke. “Remembering Ed Berger.” Current Research in Jazz 9, (2017).

- MLA 7th ed.: Fitzgerald, Michael, et al. “Remembering Ed Berger.” Current Research in Jazz 9 (2017). Web. [date of access]

- APA 6th ed.: Fitzgerald, M., Demsey, D., Snyder, M., Pullman, P., Ortiz de Urbina, F., Sultanof, J., ... Sandke, R. (2017). Remembering Ed Berger. Current Research in Jazz, 9 Retrieved from http://www.crj-online.org/

For further information, please contact:

Except where otherwise noted, content on this site is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License

This page last updated May 28, 2017, 13:41