“Ecos de México”: Young Scott Joplin

and His Secret Role Model

Marcello Piras

Background

In the 19th century, not even one of the musical styles rooted in the United States soil was suited for export. Native cultures developed no modern genre that non-natives could find interesting or even understandable, as happened in the Andes or in Guatemala. The dominant white Anglo-Saxon society had but a minimal interest in music, which looks even more negligible when compared to its interest in business. The USA, before the flood of immigrants from highly musical ethnicities (Jews, Italians, Russians), was a weak, peripheral, shallow musical copy of England, which in turn was by far the weakest nation in European concert music — a major political power with no great composers and no national style. In this perspective, 19th-century USA, Canada, UK, and Australia can be described as an integrated Anglophone musical area where common people stuck to country folk songs and dances plus religious hymns; notated music was dominated by trivial parlor music, military marches, and comedy; German symphonic music was revered as a higher genre that almost nobody understood; and finally, Italian opera was loved, but not seen as the true benchmark of refined musical taste. Local composers dished out either undistinguished songs, waltzes, and hymns, or lifeless imitations of German music. The happy, sensual French musical oasis in New Orleans was as isolated as a yellow-flagged boat. Louis Moreau Gottschalk had been chased away using the bigots’ favorite weapon — a sex scandal. His name had become taboo almost overnight.

It is no surprise that almost nothing in mainstream North American music was of interest in Europe. Gottschalk had been a passing exception as a great original. American copies of European genres were too weak to cross the ocean back to Europe. White minstrels could only appeal to English-speaking audiences, especially those not immune from racist feelings. In fact, their international tours routinely landed in Great Britain, Ireland, South Africa, and Australia; their impact elsewhere was almost nil. Concert Negro spirituals met with interest and appreciation, but they were seen as the musical dialect of an ethnic group, like flamenco or Cossack dances.

From this dismal panorama, the United States jumped to exporting jazz and dance music worldwide in about one generation. Such a quick reversal of the musical economy was boosted, to some extent, by the rise of the USA as a world power after 1918. Yet it had been prepared by a vital transitional era, with ragtime as its kernel. Ragtime and related genres — cake-walk, vaudeville vocal acts, banjo virtuosos, and so on — formed the first musical arena in which European models underwent an original transformation in the USA, one that could be generally described as a burgeoning Africanization. Its results began generating some interest abroad in the démi-monde of circus, light comedy, luxury hotels, and café concert, if not in the domain of high concert music.

Scott Joplin is commonly acknowledged as the greatest master of the ragtime era. Actually, he was perhaps the greatest musical genius born in the USA to that date. This fact alone raises questions: From where did he get his inspiration? Who were his role models if his nation had none to offer? The appearance of a towering genius out of the blue cannot be ascribed to individual talent only, no matter how talented Joplin was — and he was extraordinarily talented. In his formative years — the 1880s and 1890s — he had to draw from existing sources and traditions. For instance, he was aware of Stephen Foster (“Camptown Races” is paraphrased in “We’re Going Around” from Treemonisha) and could play banjo and violin, which his parents toyed with. [1] He was exposed to current musical fare from Johann Strauss — whose operetta Der lustige Krieg he could see in Texarkana as a child [2] — to John Philip Sousa. He only seems to have missed Gottschalk, who was undergoing his damnatio memoriæ during Joplin’s youth. Although each one of these ingredients peeps out on occasion in Joplin’s opus, none can singlehandedly explain how he could drift from the cemeterial politeness of English Victorian drawing-room ballad, attested in “Please Say You Will” and “A Picture of Her Face”, and find his own voice. Who, or what, made him see the light?

The Current State of Music in Mexico

In the same years, Mexico was both a music importer and an exporter. While its concert composers only had a limited domestic fame, not making it to the rest of the world until Manuel Maria Ponce (1882–1948) appeared, Mexican popular songs enjoyed a lasting international success; a few are still known. For instance, “Cielito lindo” was composed by Quirino Mendoza in 1882. Notice that the song is famous, the composer is not; the success of a tune did not guarantee its creator equal fate.

Such a golden age of Mexican notated light music appears to be significantly related to the favorable conditions — peace, stability, economic/industrial growth — that Mexico experienced under Porfirio Diaz’s stern hand from 1877 till the outbreak of the 1910 revolution. Mexico was then regularly sending its musicians to the USA; the opposite seems not to have happened. A contemporary of Joplin’s, Miguel Lerdo de Tejada (1869–1941), a pianist, composer, and conductor, roamed extensively up and down the States, reaching as far north as New York’s Carnegie Hall. The performances of a “Mexican Band” recalled by New Orleans jazz veterans almost attained a legendary status — until Jack Stewart’s research made it clear that different outfits thus called had visited the Crescent City over several decades. [3] Also, local publishing houses, such as Werlein and Grunewald, regularly kept Mexican music in print.

A Rosas Is a Rosas

One of the Mexican evergreens that conquered the USA and the world in those years was Sobre las olas, known in English as Over the Waves. As in the case of “Cielito lindo”, millions of people all over the world know it, while its composer, Juventino Rosas Cadenas (1868–1894) remains unknown to most non-Mexicans. This writer has personally verified that young people from various nations are still capable of singing this majestic waltz tune after hearing just its opening five pitches, yet they typically assume the composer to be some Viennese master.

Juventino’s biography is now reconstructed, at least in its main traits, [4] and a good part of his surviving opus is available on CD. [5] An Otomí native, [6] he was born in 1868 into an extremely poor family, in a medium-sized town then called Santa Cruz de Galeana, Guanajuato. He learned the rudiments of violin and music theory from his father, with whom he played as a street beggar. He then studied music in public school and at the Mexico City National Conservatory, for a law allowed the talented poor to attend it for free. A charismatic leader/performer on stage and a fertile composer of straight and syncopated dances, he became a name in the dance music world; his pieces, issued by Wagner y Levién, gave him national fame. Before 1890 he was already playing in a small group boasting the lineup of a New Orleans band, except for flute in place of clarinet. [7] His most famous composition — not just a song in 3/4 time, but a long, well-developed concert waltz with slow introduction, three themes and coda, lasting about five minutes — was first entitled Junto al manantial (“Near the water spring”) and then rechristened Sobre las olas (literally Over the Waves). A widely circulated legend has him introducing it with success at the 1884 World Cotton Exposition in New Orleans, at 18. This is unlikely; however, its first strain chord progression became a staple of New Orleans jazz bands as the final section of “Tiger Rag”. [8]

By January 1893, Rosas set out on a long North American tour, as a guest star of the Orquesta Típica Mexicana. After some personnel changes, the band, rechristened Orquesta Típica Ítalo-Mexicana, sailed for Cuba on another tour. Here, Juventino contracted a meningococcus bacteria, and died of mielitis. He was 26.

The main leg of that U.S. tour was a stay at the Chicago World Columbian Exposition (WCE) — a unique chance to win worldwide attention and launch an international career. On January 3, 1893, soon before the Orquesta Típica Mexicana left, El Monitor Republicano, a Mexico City periodical, [9] reported its complete lineup, which lends itself to some observations. The group, then led by flautist Antonio G. García, also boasted Julio Camacho, cornet; Norberto López, clarinet; Lucio Murillo and a ten-year-old girl, Bernarda Medina, saxophones; Manuel Pedroza, baritone saxophone; Baltasar Espinosa, Sidronio García Narro, Juventino Rosas, and Eduardo Flores, violins; Alberto Ramírez, cello; Cecilio Flores, bajo sexto (a Mexican twelve-string guitar); Antonio Montes, string bass; Alfredo Díaz, timpani; plus two little girl dancers, “Manuelita” Rodríguez, eight years old, and María Isabel García, seven.

Listing them in short as cornet, flute, clarinet, three saxes, five strings, guitar, bass, and drums makes it clear how close to a jazz outfit this group was, several years before “jazz” was born — or jazz was “born” (choose your favorite quotes), and at least two decades before “jazz” dance bands with saxophones and strings, à la Paul Whiteman, are supposed to have appeared in California. No evidence is known to this writer that dance bands with a similar instrumentation were common in the USA by 1893. The saxophones, in particular, must have appeared strange to audiences from every country save Mexico and France.

In fact, such a lineup was quite new for Mexico as well; it seems to have incorporated the influence of Cuban danzón, a genre that by 1890 had reached Veracruz and was quickly spreading all over the nation. On the other hand, the bajo sexto was a strictly local specialty, as were the saxophones, well known in Mexico since Porfirio Díaz’s policy of attracting investments from France had triggered their diffusion in wind bands.

Another novelty was the idea of having the musicians perform in charro (Mexican cowboy) attire, which only later became common among mariachi bands. The Orquesta repertory included European dances, like waltz and polka, alongside Mexican dances, like the jarabe tapatío, a showcase for the girl dancers, composed by Juventino. El Correo de Laredo [10] cited it as a show-stopper they had to encore.

The musical activities at the WCE roughly fell into two groups. Official music programs consisted of four concerts per day, regularly announced in its organ, called the Daily Columbian. Rosas appeared in none of these. Then, there were innumerable venues pouring music over the millions of visitors walking up and down the fair, not only in concert halls and on band stands, but even in halls and cafés hosted inside some of the national pavilions. The Orquesta Típica Mexicana reached Chicago on May 10 and made its debut at Marlowe Theater one week later. [11] Here, as reported by El Universal, [12] it was conducted by Eduardo Flores and Juventino, who probably also doubled on cornet for a showcase piece. Still later, Julio Camacho was to be cited as conductor; perhaps the main soloists alternated in such duty.

Evidence of the Orquesta’s success is that it went on performing at this 1,200-seat venue from May 18 to 25. Again, El Universal of May 31 also reports the complete program from the evening of May 22. [13] It opened with Franz von Suppé’s Poet and Peasant overture; the second part opened with Daniel Auber’s La muette de Portici overture, two well-known light classics. The rest consisted of dance pieces, and Juventino’s works made up a good share of it. However, the Marlowe Theater — then located on 6254 S. Stewart Avenue — was judged too far from downtown and the main exhibition area. Hence, after a break, on June 9 the Orquesta resurfaced at a new address. The exact location is unclear; reports cite a “Midway Plaisance Café” that appears not to be on the official WCE maps. Perhaps they were playing at some café on the Midway Plaisance, the main avenue on which many pavilions had their entrances. Several cafés and restaurants offered musical entertainment on both sides of the Midway Plaisance, but most were located inside a national area and would naturally offer their own music; for instance, the Hungarian Restaurant displayed a Gypsy band. Hence, the place hosting the Orquesta Típica Mexicana must have been on a geographically neutral territory. If so, only one place qualifies — the Garden Café, next to the Moorish Building on the right side heading west. The Official Guide to the Midway Plaisance, a slim booklet updated on August 10, 1893, offering for a dime an accurate description of all locations on the street, has it as No. 38 of the list, with this pithy description:

This is a pleasant and satisfying resting and refreshment place, where orders are filled promptly and at moderate prices. Good music is furnished and guests are treated with civility and consideration. [14]

Whatever it was, it must have been a much better placement, one which visitors were always forced to pass by — further proof of the band’s success. In fact, its stay began on June 9 and was still going on by August 19. It certainly ended up before October 4, the Mexican Day at WCE, when the Republic was officially represented by a military band.

Another event took place in those months, on which known information is confusing and mostly third-hand. Juventino’s biographer, Helmut Brenner, reports [15] that Cuban author, Hugo Barreiro Lastra, [16] affirms that the great Cuban writer and poet, Manuel Serafín Pichardo (1865–1936), wrote in his book La ciudad blanca about the tremendous success the Orquesta Típica Mexicana had at the “Manufacture and Liberal Arts Palace” [sic], before thousands of screaming people. This long chain of vague references is broken at some point. Pichardo penned a series of witty correspondences from the WCE, most — or all — of them for the noted Cuban periodical, El Fígaro. These were actually collected in a book entitled La ciudad blanca. [17] But there is not a word on Juventino in there. The preface, by Enrique José Varona, is dated January 19, 1894, proving that this was an instant book hastily dished out by the same publishing house also issuing El Fígaro, probably to cash in on the popular interest about the WCE. As we are about to see, Pichardo did write an article on Juventino, but only after the book was out, hence it could not have been selected for inclusion. Barreiro Lastra erroneously thought the article was in La ciudad blanca, and Brenner followed in the latter’s footsteps, thus spreading further the mix-up.

We are on a better track if we follow another noteworthy Cuban intellectual, the eclectic Andrés Clemente Vázquez Hernández (1844–1901), journalist, writer, lawyer, law scholar, and chess player/theorist. Some of his writings were collected by 1898 in a book, En el ocaso. Reminiscencias americanas y europeas, containing a chapter on Juventino, “Over the Waves” (en casa de los esposos Crusellas). Carta abierta a la egregia poetisa y desolada señora Luisa Pérez de Zambrana. [18] Vázquez’s open letter is dated La Habana, January 24, 1894. It is a long, rambling laudatory portrait of Juventino, written soon after his arrival in Cuba (and his U.S. tour), when the young Mexican violinist was at the peak of his fame. Sobre las olas, he wrote:

. . . .[l]o mismo se toca en la Habana por las músicas militares, que por los pianos de las señoritas; que ya suena en los parques y en las alamedas, cuando no se escucha original y velado en el silbido de los gamines de la ciudad de la Habana. [19]

A passage on one girl dancer is especially interesting:

De Manuelita Rodríguez, mexicanita de once [sic] años, que viene con la compañía, y que ha encantado a los visitantes de la Exposición Universal de Chicago, asombrándolos con su nuevo modo de bailar — siempre sobre la punta de los piés, y con la actitudes del más gracioso pudor — ¿para qué hablarle? En un próximo número de El Fïgaro se publicará su retrato, y el hábil pincel del Sr. Pichardo la describirá en los salones del gran certámen de los Estados Unidos, en donde él la vió lucir y triunfar, con hurras á la República de México, repetidos por 40,000 ó 50,000 voces entusiasmadas. [20]

Hence, if Vázquez is correct, Pichardo’s article should exist in some later issue of El Fígaro. For the moment it is buried in some Cuban library, and this is the best source we could retrieve.

The colossal event Vázquez cites took place, probably between May 25 and June 9, that is, during the interval between the Marlowe Theater and Midway Plaisance Garden Café tenures. The Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building — this is its correct name — was actually a mammoth thing: it was the largest building on earth and could accommodate six baseball fields. [21] Hence, Vázquez’s figures about the audience should not be seen as outlandish. The building burned on January 8, 1894; nothing survives. The Orquesta Típica Mexicana probably played there just once, for its immense hall was much in demand.

Before leaving Mexico, Juventino had written and published four pieces specifically for the WCE: Soledad, a waltz; Flores de México, a polka; Flores de romana, indicated as a danzón but actually a Cuban danza or habanera, as we shall see; and Flores de margarita, another waltz. All were issued by Eduardo Gariel of Saltillo, Coahuila, [22] and bore the same underlined sentence on the upper part of their frontispices: Edición especial para la Exposición Colombiana de Chicago 1893. It was a timely move, for the WCE had competitions and prizes in all fields and for all sorts of products. Rosas, alone or with the Orquesta Típica Mexicana, won four gold medals and diplomas of honor. The medals are visible on Juventino’s most famous photo, [23] apparently shot soon after the WCE. He appears wearing the Orquesta Típica charro attire, medals proudly pinned onto his chest.

It must be stressed that the WCE also had many black visitors. Some of them wrote down their comments, partly collected in Lynn Abbott’s and Doug Seroff’s book, Out of Sight. We also know from multiple sources that Scott Joplin was at the WCE. [24] Details on his activity are scanty and hard to verify, however he probably performed with his Texas Medley Quartette, a vocal group for which he was singer, composer, arranger, and may have played the piano. On August 22, the group received a short but very positive paragraph in the Cedar Rapids Evening Gazette, [25] citing that it was coming from Chicago. There can be little doubt that Joplin toured the Fair and listened to as much music as he could; never in his life was he to be given another chance to listen to Sousa, Dvořák, Paul Olah’s Hungarian Gypsy band, Brazilian sertão dances, the African musicians at the Dahomey Village, Egyptian and Turkish music, and much more, in such a virtually daily diet. The Orquesta Típica Mexicana had been prized as the best at the WCE — outside the classical-symphonic domain — and remained available daily until August, or even longer, on the Midway Plaisance. Common sense suggests that Joplin listened to Juventino. As to evidence, you be the judge.

The Negro Identity in Music

To put the events in their proper historical frame, one has to focus on Joplin’s developmental stage at that time. He was 26 and had studied in Texarkana with Julius Weiss, who apparently taught him music reading, theory, harmony, and piano, but no composition, a field in which he just pointed his pupil to some lofty models. [26] Soon after, Joplin plunged into a wandering life, often performing with his Texas Medley Quartette, writing songs for it, as well as adapting and harmonizing popular melodies.

The 1890s also saw the gradual appearance of “rags.” The earliest occurrence of this word in print was already decades old [27] and shows that it originally indicated a private ball. When organized by a black family, it was roughly similar to a 1920s Harlem rent party — a way to collect the money to pay rent. Only over time did the word migrate from the social ritual to a specific music genre people danced to in such events, born out of applying syncopation and African time-line patterns onto straight European dances, such as the polka.

Meanwhile, the burgeoning black bourgeoisie was struggling to achieve higher living standards, despite its being caught in the stranglehold of the post-Reconstruction Jim Crow revenge. Thus it began enjoying not only social dances, but also concert music. The problem of the American Negro’s national musical identity emerged — and found a preliminary solution in the work of John William Boone.

Drawing from the example of Franz Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsodies — No. 6 was a fixture in his repertoire [28] — Boone wrote virtuosic piano pieces, bearing such titles as Caprice de concert, in which Negro folk airs were embedded, more or less in the same guise as the Gypsy motifs Liszt had used. Syncopation also began creeping into Boone’s musical language. However, his compositions, as robust and sometimes even powerful as they were, never achieved a thorough sense of unity and spontaneity. Its folk strains tended to sound unnaturally coupled to a panoply of virtuoso patterns invented elsewhere.

While Boone’s experiment operated in a top-down direction, as it were, ragtime pioneers such as Thomas Turpin worked the other way around. Turpin created short, supple dance pieces, which bear the mark of extemporization even when committed to paper, [29] but also boast the formal clarity, elegance, and distinction of good composed music. They began to appear in print by 1897 (“Harlem Rag”) but were already being circulated before the WCE. [30] Their limits were in the actual lack of a concert music breadth: those lovely little creatures, albeit suited for their goal, were seemingly not endowed with the emotional power required to sustain the attention of a seated audience.

The problem was largely one of balance. On one hand, the black bourgeoisie was imitating the usages of its white counterpart, on the other it aspired to give such usages a Negro twist. Elsewhere [31] I have called it a “cuckoo’s nest“ strategy — in short: go where whites go, do what they do, and lay your African imprint there. Such tendency was then in use everywhere from Toronto to Buenos Aires. But in other nations it had an earlier, sometimes much earlier start — perhaps by 1730 in Saint-Domingue and Brazil, or even by 1690 in Mexico. [32] Also, notated music enjoyed there a higher social status and a more widespread respect and interest, it was better known, more often read and played, and included better composers. Haitian slaves, striving to access a French-oriented, French-educated musical environment, ended up playing the violin in Grétry’s operas. [33] As for Brazil, blacks could even become chapel masters or publish music theory books. [34] But what about, say, Tennessee blacks? They had little to pick up from their Anglo-Saxon neighbors’ meager musical life. As a result, the cuckoo’s nest strategy gave uneven fruits. New, original, richly syncopated genres of African-influenced notated music, such as Cuban danza, were giving birth to masterpieces in Latin America many decades before the U.S. had even gulped the rudimentary cake-walk syncopation.

Joplin, almost single-handedly, closed this gap. The embryonic state of black notated music in the USA can be measured by the reactions to the Dahomey musicians playing at the WCE. Noted black intellectuals protested against the display of such primitive Negroes, who would put the entire race in a negative light. [35] It is probably true that the WCE organizers cunningly managed to represent Africa as savage. But one would also expect that such a unique chance to hear real West African music would rather raise a stir than be regretted. The fact is, by 1893 that music was too strong a beverage even for U.S. blacks, let alone for anybody else around. Treasuring its intricate time-line patterns and interlocking, writing them down, and using them to compose original music was ahead of anybody's abilities in both musical theory and practice.

On the other hand, the Orquesta Típica Mexicana offered the ideal combination. Its music was based on familiar forms and genres, such as waltz and polka. It boasted some strongly expressive melodic material, due partly to Juventino’s own merits, partly to the all-pervading influence of Italian opera, way more inspiring than colorless English hymnody and marches. And it was also sprinkled with a dose of African-derived rhythmic accents that much exceeded U.S. current fare, but was nonetheless notated, printed, and ready for use. Joplin must have found that Juventino’s music came closest to what was confusedly emerging in his head — to create Negro notated music that could be danceable while also sporting concert music dignity.

Theory to Practice

While busy reconstructing Joplin’s mental ruminations at the Fair, this writer also began wondering whether any evidence of Juventino’s example could be found in his musical output. Combing his complete works in search of evidence soon yielded unexpected results.

Many years ago, I conceived and oversaw a three-CD complete recording of Joplin’s piano music on a period instrument, for various reasons still unpublished. I wanted to present the music in as close to chronological order as possible. We only have publishing dates for Joplin’s pieces, and these generate a partly different order, with most pieces in place except some early ones, incongruously sitting among more advanced ones. Thus, I tried to pinpoint those compositions that, on stylistic grounds or other evidence of sort, suggest their having been written years before being published. I soon focused on The Augustan Club Waltzes, issued in 1901, after Joplin had already penned such original creations as Maple Leaf Rag and The Ragtime Dance, in which every single bar sounds like him. Even at a cursory reading or listening, The Augustan Club Waltzes does not sound like Joplin at all. It could have been dished out by dozens of obscure 19th-century tunesmiths, and shows only tenuous hints of talent. I thought it might have drawn inspiration from Émile Waldteufel’s world-famous waltzes. I was wrong, but I was right in tentatively giving it the oldest date in Joplin’s opus — ca. 1895.

Joplin’s real model here is Juventino’s waltz, Carmen, issued in 1888. It was dedicated to Porfirio Díaz’s spouse, Carmen Romero Rubio, and its performance was mandatory for every band in Mexico when she was present. Rosas played it almost every night. Similarities between Carmen and The Augustan Club are astonishing as soon as their first strains are compared.

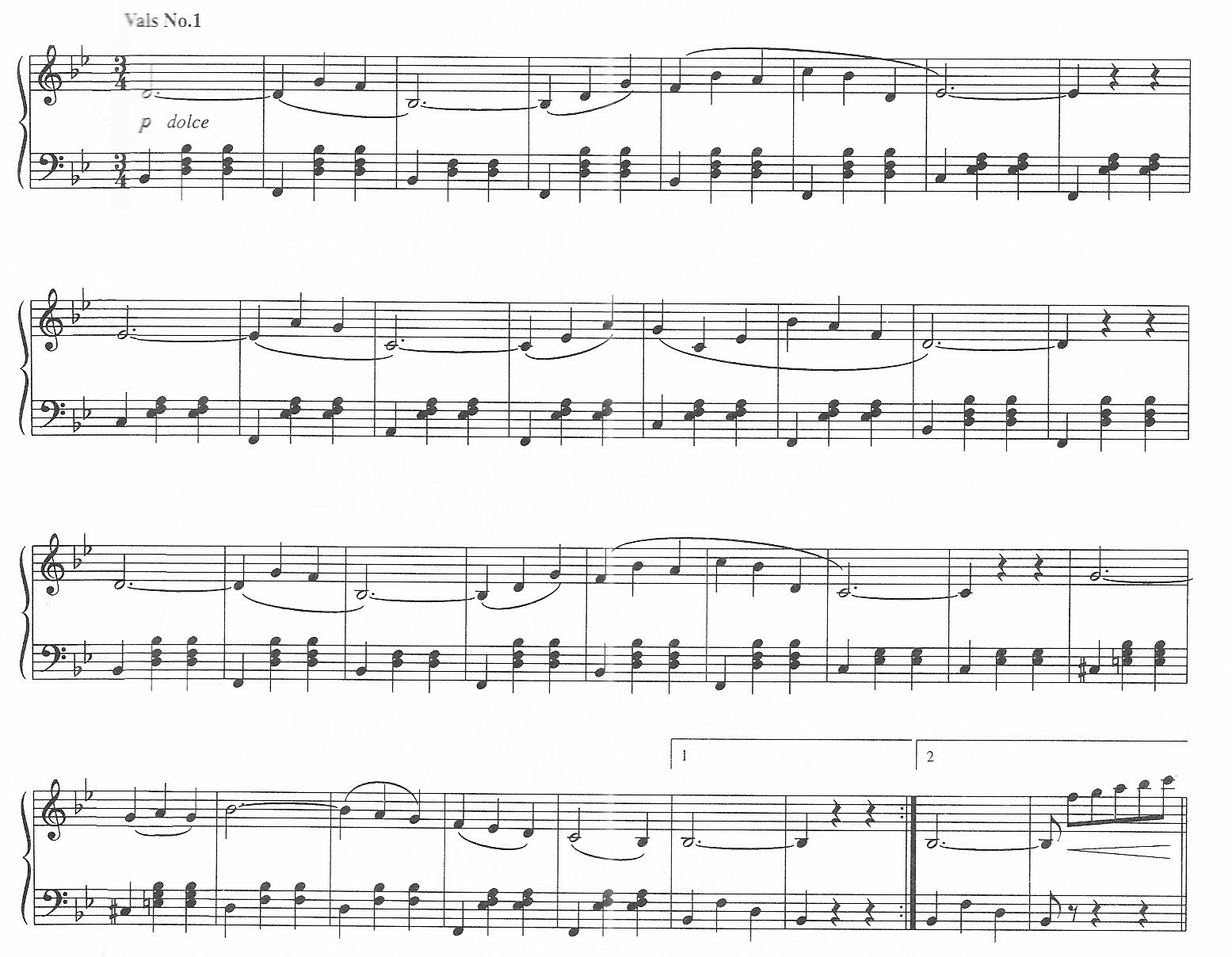

Example 1. Juventino Rosas, Carmen, A strain.

Example 2. Scott Joplin, The Augustan Club Waltzes, A strain.

Joplin’s right hand actually plays two parts — a main melody interspersed with silence, contrasted by some fill-in embroidery, in Austrian Jodler fashion. If the latter part is removed, the weight of the similarity between Rosas and Joplin becomes staggering. The two pieces are in the same key, both bear the double indication p and dolce, and sound comfortable when played at the same standard Viennese waltz tempo (about 69 per bar). Joplin’s opening pattern mimics Juventino’s — it keeps the same rhythmic contour, while the first pitch is D instead of B-flat, and the fourth one is a B-flat an octave higher.

Then, as the left hand is compared, something even more startling emerges. It is copied note for note! The chord progression is identical, only chords are typically moved a third higher (e.g. the opening D–F–B-flat becomes F–B-flat–D). The bass notes are also identical, except that those on bb. 11 and 13 are swapped, b. 22 is B-natural, not B-flat, and from b. 24 they are also raised up a third. Joplin actually took the harmonic foundation of the A strain from Carmen, then wrote his new-but-related melody above the given changes, a bit like Charlie Parker was to build “Scrapple from the Apple” on “Honeysuckle Rose”. In later years, Joplin did the same, only in more sophisticated ways, with his own chord progressions, using Maple Leaf Rag as a springboard for The Sycamore, Leola, The Cascades, Gladiolus Rag, and Sugar Cane.

The respective B strains show a more limited similarity, which finally disappears as Joplin’s waltz gradually drifts away from his model. Occasional similar patterns, such as repeated right-hand chords, appear displaced.

All in all, the beginner composer chose to start from a solid anchoring, as if feeling insecure, and selected a composition and a composer he felt affinity with. All this could have been done at any time, including the publication year 1901, but is more convincingly dated soon after the WCE, before Joplin wrote any other known piece, before his style and writing technique were ripe, and while still under the vivid impression of hearing and seeing Rosas. In fact, shortly after the WCE, Joplin resorted to enrolling at the Smith College, Sedalia, where he must have taken those composition classes that were beyond old professor Weiss’s abilities. The Augustan Club Waltzes may well be one of his earliest efforts. For these reasons, a date around 1894 might be suggested. This said, publication in 1901 is easily explained: by January 1900 Joplin was commissioned, or conceived himself, a suite of dance pieces, “such as a waltz, march, polka, schottisch, and ‘rag’,” dedicated to that club, portraying all the gamut of period dance music styles from straight to syncopated. [36] He had no reason to compose a good old waltz from scratch, when he had an old one ready. (Nothing is known about the rest of the suite).

The derivation of The Augustan Club Waltzes from Carmen is no isolated case. At least another one occurs in a later piece, more in Joplin’s mature vein.

As we said, Rosas had four compositions printed before the Chicago trip. Flores de romana occupies a special place among these. It was issued as a danzón but, you know, publishers usually prefer to pigeonhole a piece under the latest and most fashionable category, rather than under a correct but outdated one. However, the piece was no danzón at all, as it displays neither the overall four-strain form, nor the typical cinquillo pattern of such genre. It is squarely in the realm of Cuban danza and not far from its stylized export form, the habanera. There is even a passing bow to the Habanera Op. 21 No. 2 by Pablo de Sarasate, who had performed in Mexico in 1890. [37]

The basic element of a habanera is the dotted rhythm in the bass, combined with a superimposed eighth-note triplet in the melody. Of course there is more than that in Flores de romana, which, as a largely syncopated piece, must have stirred Joplin’s interest. There is no evidence whatsoever that Joplin was already playing and/or composing syncopated music by 1893. He himself said that ragtime got a significant boost from the WCE, and may have well been hinting at himself in this respect.

At any rate, Mexico and the Caribbean were much more advanced than the USA in terms of both quantity and variety of syncopation. After all, the import of African slaves to the Americas had begun there by the early 16th century, when no English colony existed, and the first African-influenced composition in Mexico was notated in 1609, [38] when a handful of English colonists could barely survive on the American soil. Now, if we translate staff notation in the handier African time-line pattern concept, every syncopated bar or group thereof can be seen as a cycle in which a pair number of impulses is divided into two odd-numbered subgroups. For example, a 2/4 bar makes a cycle of eight sixteenth notes. The Charleston rhythm splits it in a 3+5 pattern. As unsyncopated music is invaded by syncopation, such conquest follows a standard pattern, showing how rigid-torso cultures — in Alan Lomax’s terminology [39] — resist multi-unit-torso influence. The shortest and simplest 1+3 pattern appears first, then 3+5, and finally — if ever — 5+7 and 7+9. During the 19th century, syncopation appears in the USA only as the most rudimentary 1+3 pattern, associated with the cake-walk and already found in minstrel songs. Joplin’s Original Rags makes a quantum leap in this sense, lavishly resorting to the 3+5 pattern. Meanwhile, syncopation in Cuban contradanza had been present since the early 19th century and by the 1890s had reached a spectacular variety of cycles and cross-rhythms. Rosas himself was hardly the most daring musician from the Caribbean basin, yet his Flores de romana must have sounded like a revelation to Joplin and other colleagues, still being fed a daily diet of 1+3 cake-walk musical hiccups. They must have avidly jumped on Juventino’s printed pieces, in search of the key to understanding, notating, and mastering their own Afro-U.S. syncopated folk strains.

A comparison between the B strain from Flores de romana and the D strain from Joplin’s The Strenuous Life, issued in 1902, shows how Joplin worked out such influence. Clearly, at this more mature stage he no longer copied — he rather creatively rehashed whatever inspirational source he chose to work on.

Example 3. Juventino Rosas, Flores de romana, B strain.

Example 4. Scott Joplin, The Strenuous Life, D strain.

The two pieces are intended for different dance steps, hence exhibit different left-hand patterns. But harmonic functions are identical, but for few details. In fact, whoever is conversant with Joplin’s music is primarily impressed by the fact that Rosas sounds so Joplinesque! Also, Joplin’s main motif in the melody (beginning with two more notes in the anacrusis, not shown in the example) appears related to the one in Juventino, although transposed from E-flat to F. The original revolves around the fifth degree, Joplin’s one around the sixth and then fifth degree, an its contours are reversed (up-and-down becomes down-and-up) and intensified.

The Strenuous Life is too ripe and distinctive to be dated 1893, although — I feel — not enough for 1902, when Joplin was about to produce such an intricate towering masterpiece as Weeping Willow Rag. If I look at the whole picture, it suggests to me an intermediate date, let us say ca. 1898–99, that is, a piece developed from a 1893 motif at a slightly later date.

Conclusions

Whatever our conclusions on dates, these two examples show that Joplin’s interest in Mexico was much older than Solace (1909). He was born in Texas one generation after that land was sliced away from Mexico. He had been an avid music listener since his childhood, and lack of interest for the, then, productive and inspiring Mexican scene would be inexplicable on his part. Joplin’s relationship to Mexico was perhaps not so intense and deeply ingrained in his subconscious as Charles Mingus’s in his era, yet it must have been more significant than the one entertained by such composers as Gershwin, Ellington, and Copland, all of which did write Mexican-inspired pieces of some (uneven) interest. This fact opens up an entirely new research area, for Rosas was neither the first nor the only one who composed in such a style. Hence, still earlier Mexican influences on Joplin are a possibility well worthy of exploration.

Far from representing a mere incident in Joplin’s career, Juventino’s influence appears to be part of a long row of inputs from black, white, and — now we know — Amerindian composers that Joplin absorbed throughout his life. This includes contributions from German, Austrian, Italian, and Gypsy music, and from Indian religion and philosophy, [40] plus others that we hope to document in the future.

All this does not imply in the least that his main West African cultural root be underestimated or marginalized. On the contrary, it is exactly Joplin’s deeply African, all-embracing worldview — as opposed to the anal-retentive refusal of cross-fertilization then predominant in the USA — that allows and justifies his absorption of ideas from all parts of the world in the form of an uninterrupted challenge, expansion of his own self, and trans-cultural dialogue.

Perhaps it is this very word, “dialogue”, that makes Joplin’s aesthetic and philosophical teaching so eloquent, and its dissemination so urgent in today's world, still prone to political and cultural warfare.

Bibliography

- Abbott, Lynn, and Doug Seroff. Out of Sight: The Rise of African American Popular Music, 1889–1895. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2002.

- Barreiro Lastra, Hugo. Los días cubanos de Juventino Rosas. Guanajuato: Nuestra Cultura, 1994.

- Berlin, Edward A. King of Ragtime. Scott Joplin and His Era. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012

- Brenner, Helmut. Juventino Rosas. His Life — His Work — His Times. Warren, MI: Harmonie Park Press, 2000.

- Camier, Bernard, and Laurent Dubois. “Voltaire, Zaïre, Dessalines: Le Théâtre des Lumières dans L’Atlantique français.” Revue d’histoire moderne et contemporaine 54, no. 4 (December 2007): 39–69.

- Edwards, Bill. Tom Turpin, http://ragpiano.com/ragtime3.shtml (click on Tom Turpin’s name).

- Flinn, John J. (comp.). Official Guide to the Midway Plaisance. Chicago: The Columbian Guide Company, Administration Building, World’s Columbian Exposition, 1893.

- Fuell, Melissa. Blind Boone: His Life and Achievements. Kansas City, MO: Burton Pub. Co., 1915.

- “Local News.” Cedar Rapids Evening Gazette, August 22, 1893, 5.

- Lomax, Alan. “Dance Style and Culture.” Chapter 10 in Folk Song Style and Culture. Washington, DC: American Association for the Advancement of Science, 1968.

- Official Description of the Fancy Rag Ball. Baltimore: Published by the managers, 1829.

- Pichardo, Manuel Serafín. La ciudad blanca. Crónicas de la Exposición Colombina de Chicago. La Habana: Ediciones “El Fígaro”, 1894.

- Piras, Marcello. “Treemonisha or Der Freischütz Upside Down.” Current Research in Jazz 4, http://www.crj-online.org/v4/CRJ-Treemonisha.php

- “President Pleased.” The Sedalia Democrat, January 8, 1900, 7.

- Stewart, Jack. “The Mexican Band Legend: Myth, Reality, and Musical Impact; a Preliminary Investigation.” Jazz Archivist 6, no. 2 (December 1991): 1–11; 9, no. 1 (May 1994): 1–17; 20 (2007): 1–10. http://jazz.tulane.edu/jazz-archivist.

- Vázquez, Andrés Clemente. En el ocaso. Reminiscencias americanas y europeas. La Habana: Imp[renta] del Avisador Comercial de Pulido y Díaz, 1898.

References

This essay was originally conceived as a paper for the conference, “African-American Music in World Culture: Art as Refuge and Strength in the Struggle for Freedom,” held at Boston University, March 18–22, 2014. It was delivered on March 20, with Joshua Rifkin and Ran Blake in attendance. It was then integrated for a projected volume hosting the proceedings of the meeting, which was not issued. Prof. Allison Blakely has my deepest gratitude for his kind assistance in the editorial process. The text has been further revised and updated for this edition. Many thanks to Edward Berlin for his kind help.

[1] All biographical info about Joplin comes from Edward A. Berlin, King of Ragtime. Scott Joplin and His Era. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012, except as noted.

[2] Marcello Piras, “Treemonisha or Der Freischütz Upside Down.” Current Research in Jazz 4, http://www.crj-online.org/v4/CRJ-Treemonisha.php (retrieved July 16, 2015, like all URLs in this essay), no pagination.

[3] Jack Stewart, “The Mexican Band Legend: Myth, Reality, and Musical Impact; a Preliminary Investigation.” Jazz Archivist 6, no. 2 (December 1991): 1–11; 9, no. 1 (May 1994): 1–17; 20 (2007): 1–10. All three issues also available as PDF files at http://jazz.tulane.edu/jazz-archivist. The second installment has, on page 4, a concert program issued on the Daily Picayune, July 13, 1890, listing a performance of Over the Waves. On page 5, the cover of New Orleans publisher Junius Hart edition of the same piece is reproduced, bearing a November 8, 1889 inscription.

[4] Several books on Rosas have been written, some quite fictional. The best scholarly study is Helmut Brenner, Juventino Rosas. His Life — His Work — His Times, (Warren, MI: Harmonie Park Press, 2000). This is now the definitive text on the composer. All biographical info on Rosas cited here comes from it, except as noted.

[5] Obras para piano de Juventino Rosas interpretadas por Nadia Stankovitch, Vol. 1 and 2 FONCA (Fondo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes), serie Clásicos Mexicanos, SDX 21017 and 27102.

[6] The Otomí ethnic group is the fifth largest native group by population size in present-day Mexico (ca. 650,000 people, according to 2000 census data), as well as one of the poorest. It is mostly located in and around the state of Querétaro, with some Southern ramifications into the state of Tlaxcala. Many Otomís, still today, are illiterate and/or do not speak Spanish.

[7] See the famous photo of the Orquesta José Reyna, in which actually Juventino sits at the center like a leader, in Brenner, Juventino Rosas, 35.

[8] Several pieces have been suggested over the years as possible sources of this rather common chord sequence. However, Sobre las olas seems to be the oldest known candidate for which actual significant circulation in pre-1917 New Orleans is attested.

[9] Brenner, Juventino Rosas, 45.

[10] February 8, 1893. Cited in Brenner, Juventino Rosas, 45–47.

[11] On May 18. Brenner, Juventino Rosas, 48.

[12] Julio Paulat, “‘El Universal’ en Chicago,” in El Universal, May 31, 1893. Cited in Brenner, Juventino Rosas, 48.

[13] Photoreproduced in Brenner, Juventino Rosas, 49.

[14] John J. Flinn (comp.), Official Guide to the Midway Plaisance, (Chicago: The Columbian Guide Company, Administration Building, World’s Columbian Exposition, 1893), 36.

[15] Brenner, Juventino Rosas, 48.

[16] Hugo Barreiro Lastra, Los días cubanos de Juventino Rosas, (Guanajuato: Nuestra Cultura, 1994), 29.

[17] Manuel Serafín Pichardo, La ciudad blanca. Crónicas de la Exposición Colombina de Chicago, (La Habana: Ediciones “El Fígaro”, 1894).

[18] Andrés Clemente Vázquez, En el ocaso. Reminiscencias americanas y europeas, (La Habana: Imp[renta] del Avisador Comercial de Pulido y Díaz, 1898), 118–125. Chapters are unnumbered. The cited chapter title means: “Over the Waves. At the Crusellas’s. Open letter to the dear poetess and devastated lady, Luisa Pérez de Zambrana.”

[19] “[It] is played in Havana by military bands as well as by maiden pianists. It can be heard through parks and poplar line lanes, or else, original and veiled, in the whistling of Havana gamines.” Vázquez, En el ocaso, 119.

[20] “About Manuelita Rodríguez, a Mexican little girl of 11, who comes with the company and has fascinated the Chicago World Exposition visitors, astonished by her new dancing style — always on tiptoes and with the loveliest modesty — why should I spend words? In a forthcoming issue of El Fígaro her portrait will be published, and Señor Pichardo’s deft paintbrush will describe her in the halls of the great U.S. competition, where he witnessed her shine and triumph, with hurrah to the Mexican Republic, repeated by forty or fifty thousand enthusiastic voices”. Vázquez, En el ocaso, 122.

[21] http://www.domu.com/chicago/history-map/columbian-exposition-manufactures-and-liberal-arts-building.

[22] Plate nos. E.G. 14, 16, 18, and 17, respectively.

[23] Visible at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juventino_Rosas and elsewhere.

[24] Berlin, King of Ragtime, 10.

[25] “Local News.” Cedar Rapids Evening Gazette, August 22, 1893, 5.

[26] Piras, “Treemonisha.”

[27] The oldest one known so far seems to be in a 16-page anonymous pamphlet, Official Description of the Fancy Rag Ball (Baltimore: Published by the managers, 1829), describing a charity ball held at the Baltimore Atheneum on March 2, 1829.

[28] Melissa Fuell, Blind Boone: His Life and Achievements, (Kansas City, MO: Burton Pub. Co., 1915), passim.

[29] Some of his repeated strains do not have repeat signs, but are written again in a slightly varied form, apparently emulating improvisational practices.

[30] Bill Edwards, Tom Turpin, http://ragpiano.com/ragtime3.shtml (click on Tom Turpin’s name).

[31] Piras, “Treemonisha.”

[32] Such is the conjectural date for the Códice Aguirre, a manuscript tablature for the cittern and Baroque guitar.

[33] Multiple references in Bernard Camier, Laurent Dubois, “Voltaire, Zaïre, Dessalines: Le Théâtre des Lumières dans L’Atlantique français,” in Revue d’histoire moderne et contemporaine 54, no. 4 (December 2007), 39–69.

[34] Brazil boasted many composers of African descent in the 18th century. One of them, Luiz Álvares Pinto (1719–1789), also published two books, Arte de solfejar and Múzico e moderno systema para solfejar sem confuzão.

[35] Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff, Out of Sight: The Rise of African American Popular Music, 1889–1895, (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2002), 286.

[36] “President Pleased,” in The Sedalia Democrat, January 8, 1900, 7. In the 1994 first edition of King of Ragtime, page 79, Berlin tells a somewhat different story, as he quotes only the first two sentences of the article. The entire passage is omitted in the second edition.

[37] Both pieces are in minor key and begin with an introduction in parallel octaves.

[38] Venimo con glan contento, in the Cancionero de Oaxaca compiled in Puebla by Gaspar Fernandes (ca. 1566–1629).

[39] Alan Lomax, Folk Song Style and Culture, (Washington, DC: American Association for the Advancement of Science, 1968), 222–247. Here, world cultures are classified into two groups, using torso either as a single block or as two independent parts. Anglo-Saxon cultures fall in the former group. (The categorization of rhythmic cycles is this writer’s).

[40] Piras, “Treemonisha.”

Author Information:

Marcello Piras is a retired music history professor who taught at various Italian conservatories and foreign institutions, including the Center for Black Music Research, Columbia College Chicago, and the University of Michigan, where he was executive editor of the MUSA scholarly series in 2001–02. He authored many books and essays for encyclopedias and periodicals; his most recent publication is the first Spanish translation and edition of Filippo Bonanni’s seminal 1723 organology treatise, Gabinetto armonico, a two-volume set, that was awarded the 2017 Premio Antonio García Cubas as best facsimile edition of the year by the Mexican government. He is now a member of the editorial board of Analitica — Rivista on line di studi musicali. He currently lives in Puebla, Mexico, studying the black influence on colonial Baroque music and working on an Afrocentric music history from Stone Age to present, integrating data from paleontology, brain evolution, comparative linguistics, and archaeology.

Abstract:

Ragtime was the musical style that transformed the United States from musical importer to exporter. Because of such a watershed place in history, it embraces a variety of foreign influences, many still undetected. Scott Joplin apparently saw Mexican composer Juventino Rosas Cadenas as a reference model in his own search for a musical style that could form the black American equivalent of European national schools in music. He could have heard Rosas at the 1893 Columbian exposition, and evidence of such contact can be found in his opus.

Keywords:

Juventino Rosas, Scott Joplin, ragtime, jazz

How to cite this article:

- Chicago 15th ed.: Piras, Marcello. “‘Ecos de México’: Young Scott Joplin and His Secret Role Model.” Current Research in Jazz 10, (2018).

- MLA 7th ed.: Piras, Marcello. “‘Ecos de México’: Young Scott Joplin and His Secret Role Model.” Current Research in Jazz 10 (2018). Web. [date of access]

- APA 6th ed.: Piras, M. (2018). “Ecos de México”: Young Scott Joplin and His Secret Role Model. Current Research in Jazz, 10 Retrieved from http://www.crj-online.org/

For further information, please contact:

Except where otherwise noted, content on this site is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License

This page last updated December 31, 2018, 16:37