Lucky Thompson In Paris: The 1961 Candid Records Session

Noal Cohen and

Chris Byars

Introduction

Unauthorized recordings of live jazz performances can be a thorn in the side of musicians but of enormous value to the historian who is in a constant search for additional examples of a subject’s creativity. Besides featuring solos that are often less inhibited and more adventurous than those recorded in a studio setting, live sessions can also provide important information not found elsewhere. For better or worse, jazz aficionados have historically recorded live music and radio broadcasts for their own use and shared them with like-minded individuals. Often the audio quality of these amateur recordings is less than optimal and unflattering to the artists involved, but in many instances, the sound is surprisingly good. The digital age has certainly facilitated the transfer of music and it seems clear that the ready availability of recordings made without the musicians’ approval is now part of the landscape. The abundance of live performances accessible on YouTube graphically demonstrates the current state of affairs.

An instructive example of the utility of live recordings in jazz research involves the saxophonist Lucky Thompson who, in the spring of 1961, led a remarkable quartet session in Paris for the Candid Records label. At the time, only one of the eight Thompson compositions recorded was issued, the remaining tracks languishing for years before finally being released in 1997; however, the titles of these pieces had never been found. Around the same time as the Candid session, he took part in a German radio broadcast with an octet, in a program involving only his own material. Fortunately, the radio broadcast had been recorded by persons unknown and as described below, collaboration between a musician, a discographer and a record collector led to the 2006 discovery that six of the tunes from the studio session were also performed during the radio broadcast. From the radio network archives, Thompson’s titles for his songs were uncovered but this was made possible only through access to the private recording.

As to the nature of these now nearly fifty year-old compositions, careful analysis reveals subtle harmonic and structural complexities not discernable through casual listening. Although insufficiently acknowledged, Thompson was as individual a writer as he was an instrumentalist.

About Lucky Thompson [1]

Of the tenor saxophonists to emerge during the bebop era of the 1940s, Eli ‘Lucky’ Thompson (1923–2005) [2] was something of an anomaly. At a time when Lester Young and Charlie Parker were the dominant stylistic models, Thompson instead drew on Coleman Hawkins, Chu Berry, Ben Webster, and Don Byas for his inspiration, ingeniously updating those earlier influences harmonically and rhythmically to create an original sound and conception that could be adapted to almost any musical context. Tad Shull has analyzed Thompson’s style and describes it as “backward” in the sense that his phrasing is the opposite of what one might expect, with accents falling in the “wrong” places on the “wrong” beats and in the “wrong” order. [3] That such an approach was successful is a tribute to Thompson’s great talent but at the same time a hindrance to the facile categorization and assimilation of his playing. The subtleties of his innovations were difficult for many listeners, critics and musicians to fully appreciate, especially in his later years.

Thompson was born in Columbia, South Carolina but soon thereafter his family moved to Detroit, Michigan where he was raised and received his first musical training and experience. By 1943 he was a member of the Lionel Hampton orchestra. Stints with the bands of Billy Eckstine, Count Basie, and Boyd Raeburn followed. With Basie, he contributed solos to the classic Columbia recordings of “Taps Miller” (December 6, 1944) and “Avenue C” (February 26, 1945). Leaving that ensemble in the fall of 1945, he settled in Los Angeles where he made his first recording as a leader for the Excelsior label. In February and March of 1946 he was part of the landmark sessions led by Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker for the Dial label that introduced such bebop standards as “Confirmation”, “Yardbird Suite” and “Ornithology.” And in April 1947, four tracks recorded by “Lucky Thompson and his Lucky Seven” for RCA Victor attracted considerable attention, in particular, the leader’s bravura performance on the ballad “Just One More Chance.”

Through the 1950s Thompson’s style evolved, taking on more modern aspects while maintaining an originality that bridged eras. In April of 1954, he recorded two extended blues with Miles Davis for the Prestige label, making history in the process by helping to revive Davis’s flagging career and ushering in a sub-genre that would become known as hard bop. His solos on these tracks (“Walkin’” and “Blue ’n Boogie”) are models of melodic construction steeped in elegance and passion.

In the mid-1950s, Thompson’s star appeared to be rising as he turned out many memorable recordings under his own name and contributed significantly to sessions led by Milt Jackson, Jimmy Cleveland, Stan Kenton, Oscar Pettiford, and Quincy Jones to name just a few. In reality, however, his thorny personality and refusal to compromise were making survival in the music business difficult, at least in America.

Thompson spent a substantial portion of his career performing and recording in Europe. Motivated by a quest for self-expression without compromise and a deeply rooted distrust of the American commercial institutions that controlled most aspects of the music/entertainment industry, he lived in France and Switzerland for extended periods from 1956 until his withdrawal from activities as a professional musician in the mid 1970s. During this time, he performed widely throughout the Continent and participated in a host of recordings with the very finest English and European musicians as well as American expatriates including drummer Kenny Clarke, trombonist Nat Peck and guitarist Jimmy Gourley.

It was also in Europe that Thompson began experimenting with the soprano saxophone, recording on that horn for the French Symphonium label in January of 1959, over a year earlier than John Coltrane’s first soprano session. [4] But because Thompson’s French recordings were poorly distributed — not being issued in the U.S.A. until 1999 — his pioneering efforts on soprano were largely overlooked.

A prolific but largely unrecognized composer, Thompson produced a broad range of material from pop and rhythm and blues songs to complex post-bop pieces. He was also one of a small number of musicians of his era concerned with the protection of rights to their music through the establishment of their own publishing companies. Thompson railed against royalty theft and exploitation of composers by entrenched record producers and publishers throughout his career, burning bridges in the process and ending up deeply embittered by an industry he viewed as corrupt and insensitive to genuine creativity and quality. [5]

The later years of Thompson’s career (1968–1974) were characterized by a pattern of ups and downs associated with family and professional problems. [6] Even so, some fine recordings were made during this period including a session backed by the trio of the Spanish pianist Tete Montoliu and his last studio sessions done for Sonny Lester’s Groove Merchant label. After teaching briefly at Dartmouth College in the early 1970s, and only in his fifties, he left his professional life behind and settled for a time in Savannah, Georgia where Christopher Kuhl interviewed him in 1981. [7] But for years after that last known encounter, his whereabouts were a mystery until the mid-1990s when he was discovered in a homeless condition in the Seattle, Washington area. Suffering from paranoia and dementia, he spent his remaining years in assisted living facilities and nursing homes, being visited occasionally by musicians passing through the Seattle area. [8] Thompson succumbed to Alzheimer’s disease in 2005.

Session History

Between 1959 and 1962, Thompson participated in several European radio and TV broadcasts as well as film soundtrack recordings. Arguably, of greatest historical significance — although little known because nothing was ever issued commercially from them — are five NDR (North German Broadcasting) jazz workshops that took place on April 17, 1959 (No. 6), April 22, 1960 (No. 13), November 25, 1960 (No. 16), April 28, 1961 (No. 19), and May 31, 1962 (No. 25). Originating from studios in Hamburg and Frankfurt, the series was produced by Hans Gertberg and often featured original compositions by the ensemble members. The workshop of April 28, 1961 comprised all Thompson material, seventeen new pieces and two holdovers from 1956 [9] performed by an octet of five horns and three rhythm, an instrumentation that he seemed to favor throughout his career. Fortunately, collectors made recordings of these radio broadcasts, which, although unauthorized, must be considered valuable and enlightening components of Thompson’s oeuvre. Around the same time as the April 1961 broadcast, Thompson led a remarkable quartet recording in Paris for the Candid record label that forty-five years later would be found to have an important connection to NDR Workshop No. 19, as we will see.

Candid Records was formed in 1960 when Archie Bleyer, the owner of Cadence Records, asked writer Nat Hentoff to create a jazz subsidiary. Although short-lived, Candid was noted for issuing high quality, innovative material by jazz artists such as Charles Mingus, Max Roach, Abbey Lincoln, Cecil Taylor, Pee Wee Russell, Coleman Hawkins, Booker Ervin, and Booker Little as well as blues figures like Lightnin’ Hopkins. As producer, Hentoff allowed the artists wide latitude, a policy that led to groundbreaking and sometimes controversial recordings, most notably Roach’s politically and sociologically charged Freedom Now Suite. When both Cadence and Candid went bankrupt, pop vocalist Andy Williams (who had recorded for Cadence) acquired the entire catalog. Some of the jazz recordings were reissued later on his Barnaby label. In 1988 the English record producer Alan Bates took control of the Candid catalog and began to reissue on compact disc the original LPs along with some new discoveries. The London-based label is still active, offering the classic 1960s recordings as well as CDs by contemporary artists. [10]

The session Thompson recorded in Paris was not supervised by Hentoff but by the saxophonist himself. He chose as sidemen his longtime associate, bebop innovator Kenny Clarke (1914–1985) on drums, the highly original Algerian-born pianist Martial Solal (1927–), and the German bassist Peter Trunk (1936–1973).

A recipient of the prestigious JAZZPAR Prize in 1999, the versatile Solal is considered one of France’s most important jazz musicians and has recorded with a broad spectrum of artists from Django Reinhardt and Sidney Bechet to Lee Konitz and Dave Douglas. Solal also produced scores for many films. Now in his eighties, he continues to appear all over the world. Thompson and Solal collaborated on a number of sessions in France between 1957 and 1961 and recently the INA (French National Audiovisual Institute) made available a video of Thompson’s octet recorded in May of 1960 at Club St. Germain, on which both Solal and Clarke participate. [11]

Frequently associated with European stalwarts like saxophonists Hans Koller and Klaus Doldinger, trombonist Albert Mangelsdorff, trumpeters Benny Bailey and Dusko Goykovic, guitarist Attila Zoller, and violinist Jean-Luc Ponty, bassist Trunk was often found backing Thompson including a pianoless trio session for the French Vogue label in 1960 and NDR Workshop No. 19. He died prematurely in an auto accident in 1973.

Eight titles were recorded at the quartet session but only one of them, “Lord, Lord Am I Ever Gonna Know?”, was released initially (1961) on a Candid compilation called The Jazz Life! (Candid CM 8019/CS 9019). Other artists on this LP were an ensemble called the “Jazz Artists Guild” that included trumpeter Roy Eldridge, trombonist Jimmy Knepper, multi-instrumentalist Eric Dolphy, pianist Tommy Flanagan, bassist Charles Mingus, and drummer Jo Jones; blues guitarist/vocalist Lightnin’ Hopkins; the Calvin Massey Sextet; an octet led by Mingus; and a septet under the leadership of trumpeter Kenny Dorham. This was one of the last Candid LPs to be issued by the original label. The Thompson LP including all eight tracks, intended to be Candid 9035, never saw the light of day; however, tapes containing the entire session were eventually found in a Barnaby Records warehouse in Los Angeles after Alan Bates had acquired the Candid archives in the late 1980s. Unfortunately, song titles did not accompany the newly discovered tapes. Faced with a predicament, Bates and historian/critic Mark Gardner, who wrote the liner notes, decided to assign arbitrary titles to the seven previously unreleased and unnamed compositions when the CD Lord, Lord Am I Ever Gonna Know? (Candid (Eng.) CCD 79035) was finally issued in 1997. How this was done is intriguing. [12]

Included in the CD was a spoken “introduction” by Thompson himself, taped in 1968 for inclusion in a jazz symposium to be held in Coventry, England in May of 1968. Gardner was to give a presentation on Thompson’s career and music but the event never took place, apparently due to a lack of financial support. Nonetheless, the saxophonist’s thoughts, presented with piano background (presumably by him), provide insight into the way he viewed the music business as it was evolving at the time. While stated calmly and articulately, bitterness and frustration are apparent in Thompson’s comments which seem to foreshadow his decision six years later to leave his chosen profession for good. Using this introduction, Bates and Gardner selected phrases from which the titles for the newly discovered compositions were derived. They are highlighted in the following transcript: [13]

Hello Mark and hello there, everyone in England. This is Lucky Thompson here in good old New York City on a very beautiful Tuesday. I think it is March 20th in ’68. I’d like to say that I feel very warm inside knowing that I’ve been chosen by you to honor during your next convention. But I’m somewhat saddened by the fact that I feel like a man who’s being paid for something he’s yet to do and that’s due to the fact that I feel that I have only scratched the surface of what I know that I’m capable of doing. And I’m one that would like to feel worthy of such an honor as this so please bear with me and I hope that one day soon I will be able to find new openings by which to share these many blessings that God has so chosen to entrust in me.

You know, just recently I’ve discovered the fact that not only are the musicians and entertainers guilty of not assuming their proper share of their responsibilities which are necessary to help make their profession a healthy one. But I feel that you, the public, also must share a bit of this responsibility because, you see, I think, that some of you should reappraise your values these days; because, are you really buying a ticket to your favorite theater or your favorite concert hall because it’s your choice of artists that are appearing there, or is it the choice of those behind our profession whose desire is to exploit the arts and the artists and are also working overtime to make sure that you, the public, lose your freedom of choice?

For I say that to say this: That until you are sure as to whether or not the idols that you worship are of your own choosing, you are indirectly supporting those who are continuously exploiting our profession and the artist. And I just found out recently that all of us, whether large or small, whether recording companies, publishers, booking agents, et cetera, are completely dependent upon you, the public, for support. So reappraise your values and see if you can be the one to decide as to whether or not the artist or artists that you are idolizing happen to be of your own choice. This is all we ask.

And so I’d like to say thanks very much again to you, Mark, and all my friends there in England and throughout the world and I do sincerely hope that soon, in the very near future, I’ll have the privilege of being there with you once again. And until that time, God bless all of you and do me one favor, don’t forget to love and respect one another.

Lucky Thompson...ciao.

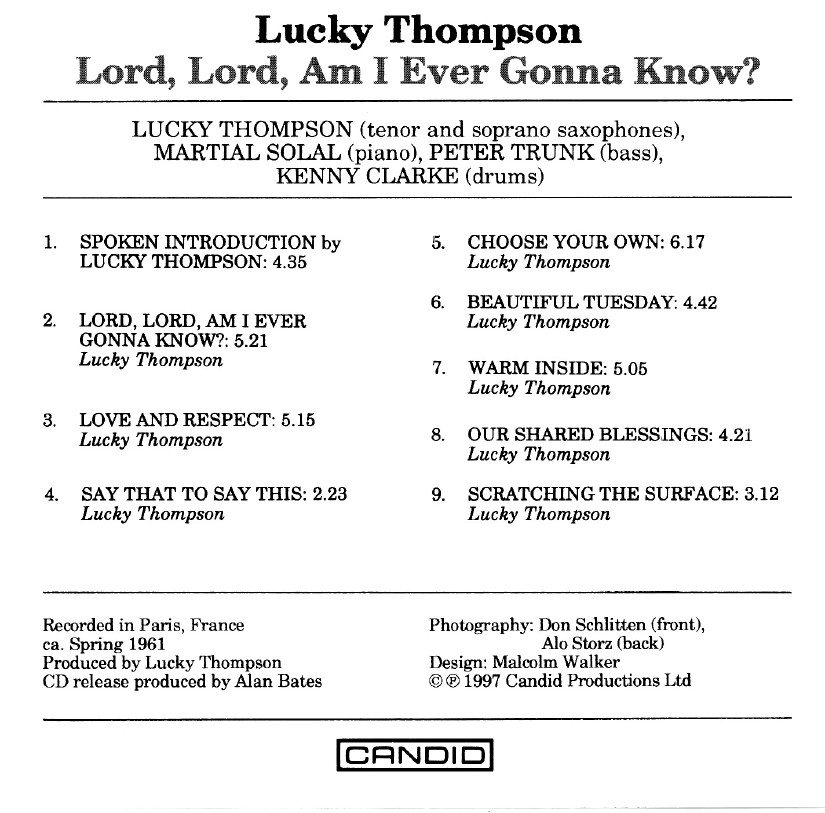

Thus the 1997 CD was issued with the following program:

Figure 1. Candid CCD 79035 back cover.

What Bates and Gardner did not know at the time was that, of tracks 3–9, all but one were performed at NDR Workshop No. 19 and Thompson’s actual titles were preserved in the NDR archives. [14] This fact was discovered in 2006 when the authors were preparing for a tribute to Thompson held on March 22–25 of that year at Smalls Jazz Club in New York City. [15] After having secured a recording of the 1961 German radio broadcast, it became apparent from auditioning the performances [16] that the title equivalences are as shown in the following table:

| Title on Candid CCD 79035 | Thompson’s Title from NDR Archives |

| Love and Respect | I Remember When |

| Say That To Say This | Sky High |

| Choose Your Own | Two Steps Out |

| Beautiful Tuesday | * |

| Warm Inside | Last Night I Met An Angel |

| Our Shared Blessings | Is the Long Road the Right Road? |

| Scratching the Surface | It’s Fantasy |

* This composition was not performed at Workshop No. 19 and does not appear on any other sources examined thus far, so its actual title remains unknown.

The discographical details then for both the quartet recording session and the NDR workshop are as follows:

Location: Paris, France

Label: Candid

Lucky Thompson (ldr), Lucky Thompson (ss, ts), Martial Solal (p), Peter Trunk (b), Kenny Clarke (d)

| a. | Lord, Lord, Am I Ever Gonna Know? - 5:21 (Lucky Thompson) / arr: Lucky Thompson

Candid (Eng.) CD: CCD 79000 — Candid Jazz (1988) Candid (Eng.) CD: CCD 79019 — The Jazz Life! (1990) JazzFest CD: 2216 — Saxophone Heroes (1997) Candid LP 12": CM 8019/CS 9019 — The Jazz Life! (1961) Candid (Jpn.) LP 12": SMJ 6188 — The Jazz Life! (1978) Barnaby LP 12": BR 5021 — The Jazz Life! (1978) | |

| b. | I Remember When (Love and Respect) - 5:17 (Lucky Thompson) / arr: Lucky Thompson | |

| c. | Sky High (Say That To Say This) - 2:24 (Lucky Thompson) / arr: Lucky Thompson | |

| d. | Two Steps Out (Choose Your Own, Two Stops Out) - 6:25 (Lucky Thompson) / arr: Lucky Thompson | |

| e. | Beautiful Tuesday - 4:47 (Lucky Thompson) / arr: Lucky Thompson | |

| f. | Last Night I Met An Angel (Warm Inside) - 5:09 (Lucky Thompson) / arr: Lucky Thompson | |

| g. | Is the Long Road the Right Road? (Our Shared Blessings) - 4:23 (Lucky Thompson) / arr: Lucky Thompson | |

| h. | It’s Fantasy (Scratching the Surface) - 3:15 (Lucky Thompson) / arr: Lucky Thompson | |

| All titles on: | Candid (Eng.) CD: CCD 79035 — Lord, Lord, Am I Ever Gonna Know? (1997)

Candid (Jpn.) CD: TECW 20490 — Lord, Lord, Am I Ever Gonna Know? (1997) | |

Lucky Thompson (ss) on b, d-e, g; (ts) on a, c-d, f, h; Thompson is unaccompanied on d.

Location: Funkhaus des NDR, Studio 10, Hamburg, Germany

Label: [radio broadcast]

Lucky Thompson (ldr), Christian Bellest (t), Nat Peck (tb), Lucky Thompson (ss, ts, con), Jo Hrasko (as), William Boucaya (bar), Carlos ‘Charlie’ Diernhammer (p), Peter Trunk (b), Daniel Humair (d)

| a. | 101 | Mr. Care Free - 6:10 (Lucky Thompson) / arr: Lucky Thompson |

| b. | 103 * | It’s Fantasy (Scratching the Surface) - 3:08 (Lucky Thompson) |

| c. | 104 | Old Reliable - 6:03 (Lucky Thompson) / arr: Lucky Thompson |

| d. | 105 * | I Remember When (Love and Respect) - 4:50 (Lucky Thompson) |

| e. | 106 | Hang Over Heaven - 3:40 (Lucky Thompson) / arr: Lucky Thompson |

| f. | 201 | It’s Thursday - 5:05 (Lucky Thompson) / arr: Lucky Thompson |

| g. | 202 * | Is the Long Road the Right Road? (Our Shared Blessings) - 4:06 (Lucky Thompson) |

| h. | 203 | Seeing Is Believing - 3:33 (Lucky Thompson) / arr: Lucky Thompson |

| i. | 205 | From Day Till Dawn - 5:21 (Lucky Thompson) / arr: Lucky Thompson |

| j. | 206 | Down the Stretch - 3:15 (Lucky Thompson) / arr: Lucky Thompson |

| k. | 301 | Check Out Time - 5:50 (Lucky Thompson) / arr: Lucky Thompson |

| l. | 303 * | Sky High (Say That To Say This) - 3:53 (Lucky Thompson) |

| m. | 401 | Could I Meet You Later? - 4:33 (Lucky Thompson) / arr: Lucky Thompson |

| n. | 402 * inc | Last Night I Met An Angel (Warm Inside) - 4:15 (Lucky Thompson) |

| o. | 404 | Notorious Love - 3:46 (Lucky Thompson) / arr: Lucky Thompson |

| p. | 405 | Minuet In Blues - 6:27 (Lucky Thompson) / arr: Lucky Thompson |

| q. | 406 | The Fire Bug - 3:50 (Lucky Thompson) / arr: Lucky Thompson |

| r. | 408 * | Two Steps Out (Choose Your Own, Two Stops Out) - 4:13 (Lucky Thompson) / arr: Lucky Thompson |

| s. | 410 | Another Whirl - 2:55 (Lucky Thompson) / arr: Lucky Thompson |

| t. | Mr. Care Free - 2:35 (Lucky Thompson) / arr: Lucky Thompson | |

| All titles unissued. | ||

Christian Bellest (t), Nat Peck (tb), Jo Hrasko (as), William Boucaya (bar) on a, c, e-f, h-k, m, o-t; Lucky Thompson (ss) on d, g, i, o-p, r; (ts) on a-c, e-f, h, j-n, q, s-t; Carlos ‘Charlie’ Diernhammer (p) on a-k, m-t.

Tracks b and n: tenor sax, piano, bass, drums only.

Tracks d and g: soprano sax, piano, bass, drums only.

Track l: tenor sax, bass, drums only.

This is a private recording (provenance unknown) of Jazz Workshop No. 19 of the Norddeutscher Rundfunk (NDR). Each title listed in the NDR archives, with the exception of track t, was assigned a number as shown. They are not consecutive because numbers were also assigned to announcements that are not shown here. Track n is incomplete with a drop out occurring during the piano solo.

* indicates compositions also performed at the Candid recording session.

The exact date of the quartet session is not known but most likely took place close in time to the radio broadcast.

The Music

Lucky Thompson is not generally known as a writer, yet to date, nearly 170 pieces composed by him have been identified. [17] Many of these are unusual and challenging and have occasionally attracted the interest of contemporary musicians. None has achieved sufficient coverage to merit the label of “jazz standard.” Pianist John Hicks reminisced about playing with Thompson early in Hicks’s career (probably 1963):

It was my first gig in New York. I got the call at my hotel. Hank Jones had recommended me to him. I showed up for a rehearsal and Lucky Thompson thumped a stack of music onto the piano that was about a foot high. He said, “Today’s a run-through.” So I said, “Which ones are we going to do?” and he said, “All of them.” Lucky was one of the most organized, motivated people I ever met. He showed me the level of effort that was required in this life to make your dreams come to reality. [18]

The pieces recorded in 1961 reveal key characteristics of Thompson’s later writing:

- Complex harmonies often strung together in unconventional ways;

- A tendency to employ different structures for ensemble and solo sections;

- Ingenious and frequent utilization and modification of the 12-bar blues form;

- An element of surprise.

“Lord, Lord Am I Ever Gonna Know?”

Of the eight compositions recorded for Candid at the spring 1961 session, no fewer than five are either conventional or modified blues, although this may not be apparent to the casual listener. This title is a 24-bar minor blues (8 + 8 + 8) with solos over the standard 12-bar blues form. The introduction is in a mysterious tonality, loosely defined as F diminished, but the presence of a C in the bass ostinato, suggests another interpretation — F minor (major 7) with a 5 and ♭5. Thompson puts melodic weight on E and B♭, the major 7 and 11, which enhance both interpretations — a unique harmonic texture. The melody continues to entertain the simultaneous presence of the 5 and ♭5, now in a “blues scale” set of pitches. The rather simple line has a catchy syncopation on beat four, and then two measures later on beat two, emphasizing different spots in the 4/4 context. This sequence is persistently repeated five times, which is beyond the typical number of repetitions for Thompson, giving the song an air of popular music. When it is time for the sixth repetition, he breaks the gloomy minor tonality of the previous twenty measures with a classic Count Basie-style major ending. It is of interest that Thompson begins his solo with the same notes he emphasized in the introduction, toying with them for the opening eight bars. They make periodic re-appearances throughout the rest of his four brilliant choruses.

- Concert key: F minor/F major; ♩ = 120

- Performance Routine

- Introduction: 16 bars (mm. 1-2: drums; mm. 3–4: bass & drums; mm. 5–12: ensemble vamp; mm. 13–14: piano; mm. 15–16; drums)

- Theme: 1 chorus (24 bars, F minor)

- Note: Solos are based on a standard 12-bar blues in F major

- Tenor saxophone solo: 2×12 bars (piano out), 2×12 bars (with piano)

- Piano solo: 2×12 bars

- Drums: 1×12 bars

- Theme: 1 chorus (24 bars)

- Faded tag ending: 10 bars

“I Remember When” (“Love and Respect”)

The first of two intriguing ballads, this exceptionally beautiful song has a 32-bar, A1/A2/B/A3 structure and is written over a cascading deluge of chords, which vary unpredictably, establishing contrasting areas of activity and brief respite. To negotiate this tune comfortably the player needs to analyze (and hear) the manner in which many of these chords relate together, grouping two, three, or four of them as movements within a common idea. The A1 chord sequence is as follows, exemplifying the harmonic complexity:

Note: This article uses interactive musical notation produced using Sibelius notation software. The Sibelius Scorch plug-in allows for musical notation to be displayed as well as heard. Transcriptions are notated at concert pitch. The play button starts playback from the beginning. Clicking on any point in the notation starts the playback from that point. Key and tempo can be changed by the user. If you do not see the score, get the Scorch plug-in here.

Example 1. “I Remember When”

Thompson’s performance demonstrates his use of the soprano saxophone as a warm, accessible instrument that invites attention instead of driving people away, as often is the case with this notoriously difficult instrument.

- Concert key: A♭ major; ♩ = 54

- Performance Routine (also for April 28, 1961 broadcast)

- Introduction: 4 bars (mm. 1–2: quartet; m. 3: piano; m. 4: soprano saxophone with ritardando)

- Theme: 1 chorus (32 bars)

- Soprano saxophone solo: 16 bars

- Piano solo: 8 bars (bridge)

- Theme: last 8 bars

“Sky High” (“Say That To Say This”)

Taken at a rapid tempo, this is a 32-bar, A/A/B/A “I Got Rhythm” variant with a difficult, chromatically descending bridge, as follows:

Example 2. “Sky High”, bridge.

- Concert key: B♭ major; ♩ = 304

- Performance Routine

- Introduction: 10 bars (mm. 1-7: quartet; mm. 8–10: drums)

- Theme: 1 chorus (32 bars)

- Interlude: 8 bars including 2-bar tenor saxophone break

- Tenor saxophone solo: 1 chorus (piano out)

- Four-bar exchanges with drums: 1 chorus (piano out)

- Piano: 1 chorus (32 bars)

- Theme: 1 chorus (32 bars)

- Coda: 8-bar reprise of introduction

On April 28, 1961, Thompson performed this tune with only bass and drums. The solo order then was: Tenor saxophone solo (2 choruses); Drum solo (2 choruses); Eight-bar exchanges with drums (2 choruses).

“Two Steps Out” (“Choose Your Own”)

This is another modified blues, now in a 20-bar format (8+4+8), that Thompson performs without any accompaniment, on both soprano and tenor saxophones and at two tempi. Again, the solos revert to the standard 12-bar blues form.

- Concert key: C major; ♩ = 164, 232

- Performance Routine:

- Introduction: 8 bars on soprano saxophone at slower tempo

- Theme: 1 20-bar chorus on soprano saxophone

- Soprano saxophone solo: 6×12 bars

- Interlude: 8 bars on tenor saxophone at faster tempo

- Tenor saxophone solo: 11×12 bars

- Interlude: 8 bars on soprano saxophone at slower tempo

- Theme: 2 20-bar choruses on soprano saxophone

- Coda: 8 bars on soprano saxophone

In contrast, the performance of this composition on April 28, 1961 involved an octet with Thompson only playing soprano saxophone:

- Concert key: C major; ♩ = 160

- Performance Routine

- Introduction: 18 bars (mm. 1–10: ensemble; mm. 11–14: drums; mm. 15–16: bass and drums; mm. 17–18: soprano saxophone)

- Theme: 1×20 bars (soprano saxophone unaccompanied until last 2 bars; 1×20 bars (soprano saxophone and ensemble)

- Soprano saxophone solo: 1×12 bars (ensemble drops out after 2 bars); 1×12 bars (with just bass and drums); 2×12 bars (with ensemble)

- Piano break: 2 bars

- Ensemble soli choruses with soprano saxophone lead: 2×12 bars

- Interlude: 2-bar breaks by piano, bass, drums, soprano saxophone

- Theme: 1×20 bars (soprano saxophone and ensemble)

- Coda: 2 bars

“Beautiful Tuesday” (Thompson’s actual title unknown)

Perhaps the most deceptive of Thompson’s compositions is this 36-bar, A1/A1/B/A2 (8 + 8 + 8 + 12) tune that again, is the blues in disguise. It is worthy of note how the A section functions perfectly as an 8-bar cell of the form, but after the bridge, receives a 4-bar extension and really sounds like a blues. He achieves this illusion with a minimum of references to the blues itself — there is no IV chord in the second or fifth measures, no I chord in the seventh measure, no ii7 in the ninth measure — yet it carries the impression of the blues from which Thompson never strayed too far. The solo structure for soprano and piano is 24 + 12: a double-length blues with a chaser of the traditional.

- Concert key: B♭ major; ♩ =148

- Performance Routine

- Introduction: 12 bars (mm. 1–8: ensemble; mm. 9–10: piano; mm. 11–12: bass and drums)

- Theme: 1 chorus (36 bars)

- Soprano saxophone solo: 1×36 bars (24 + 12)

- Piano solo: 1×36 bars (24 + 12)

- Bass solo: 12 bars (standard blues form)

- Theme: 20 bars starting at B-section

- Coda: 10 bars

“Last Night I Met An Angel” (“Warm Inside”)

The second of Thompson’s captivating ballads, this tune is notable for the subtle but rich harmonies present, which raise it above the level of the mundane. The form is 32-bar, A1/A2/B/A1. Of interest is the use of the progression I to vi7 (see A section, bars 1–4 below). Since it is the first half of a I–vi7–ii7–V7 progression, hearing those first two chords serves to establish a tonality, but Thompson does not feel obligated to complete the pattern that is so frequently encountered in jazz and pop music. In measure 2 of the three A sections (and the first half of the bridge), he returns immediately to the I, while in measure 4, he employs the “happy” II7 chord. In the second half of the bridge, a typical spot for a composer to introduce a new key, he offers a G major to E minor7, and then quickly rushes off to the distant tonality of D♭.

Example 3. “Last Night I Met An Angel”, mm.1–4.

- Concert key: B♭ major; ♩ = 56

- Performance Routine (also for April 28, 1961 broadcast)

- Introduction: rubato piano followed by a 2-bar pickup

- Theme: 1 chorus (32 bars)

- Tenor saxophone solo: 16 bars

- Piano solo: 8 bars (bridge)

- Theme: last 8 bars

“Is the Long Road the Right Road?” (“Our Shared Blessings”)

Here we have a standard 12-bar blues — almost. Thompson imbues the theme with substantial harmonic variations (shown below) that again, upon casual listening, may not convey a blues feeling. The excellent solos, however, are clearly recognizable as based on conventional blues chord changes.

Example 4. “Is The Long Road The Right Road?”

- Concert key: E♭ major; ♩ = 124

- Performance Routine

- Introduction: 8 bars with breaks by all four musicians in the following order: piano, drums, soprano saxophone, bass

- Theme: 2×12 bar choruses

- Bass and drums: 1×12 bars 4-bar exchanges (bass/drums/bass)

- Soprano saxophone solo: 2×12 bars without piano; 1×12 bars with piano

- Piano solo: 2×12 bars

- Theme: 2×12 bars

The live performance employs a somewhat different solo routine: bass: 1×12 bars; soprano saxophone: 3×12 bars (2 choruses without piano); piano: 2×12 bars.

“It’s Fantasy“ (”Scratching the Surface“)

Yet again, the blues in disguise — this time a 24-bar minor blues (8 + 8 + 8), the true nature of which only becomes apparent during the solos. There is a striking contrast between the theme, centered in F major, and the solo sections, which shift to D minor. The ease with which the quartet negotiates the challenges this difficult piece poses is quite impressive and suggests that substantial rehearsal may have preceded the session.

- Concert key: F major/D minor; ♩ = 242

- Performance Routine (also for April 28, 1961 broadcast)

- Introduction: 10 bars (mm. 1–7: quartet; mm. 8–10: drums)

- Theme: 2×24 bars (2 choruses separated by 4-bar drum break)

- Tenor saxophone solo: 1×24 bars (no piano), 1×24 bars (with piano)

- Piano solo: 4-bar break leading to 2×24 bars

- Drums: 4-bar break

- Theme: 1×24 bars

- Coda: 8-bar reprise of introduction

Conclusions

The session that Lucky Thompson recorded for Candid Records in 1961 is certainly one of his finest. His performances on both soprano and tenor saxophones are inspirational in their originality, construction, and emotional impact. He was truly a unique artist with a style that remains difficult to pigeonhole. Solal likewise shows himself here to be fully up to Thompson’s level, producing solos largely devoid of bebop clichés. And the backing of Kenny Clarke, particularly his brushwork, should stand as a model for drummers of today. In addition, we are treated to Thompson’s genius as a composer whose ability to transform fundamental jazz forms like the blues into novel and intriguing springboards for improvisation is shared by very few others.

It should also be noted that the revelations described herein clearly demonstrate the historical importance of live jazz recordings, even those that are made without authorization. Lacking access to the NDR radio broadcasts, it would have been impossible to identify the actual titles of several of Thompson’s compositions. Ideally, these performances should be issued commercially as they are certainly of sufficient quality to justify doing so from an artistic point of view. But since that has not happened and probably never will, researchers are forced to access whatever sources are available to obtain answers. In this case, musician, record collector, and discographer joined forces to shine new light on old recordings and add a few details to the legacy of a musician worthy of greater recognition.

Bibliography

- Atkins, Ronald. “Lucky Thompson In Britain,” Jazz Monthly, 8/6 (August 1962), 24.

- Carr, Ian. Miles Davis. New York: William Morrow and Co., 1982, pp. 55–57.

- Coady, Philip. “Remembering Lucky Thompson (1924–2005),” Earshot Jazz 21/9 (September 2005), 4–5, 18–19.

- Gardner, Mark & Bates, Alan. Liner notes to Lord, Lord, Am I Ever Gonna Know?, Candid CCD 79035, 1997.

- Gardner, Mark. “Lucky Thompson in the Sixties,” Coda Magazine 9/1 (June 1969), 3–8.

- Heckman, Don. “The Woodwinds of Change,” Down Beat 31/27 (October 8, 1964), 15–17.

- Hentoff, Nat. At the Jazz Band Ball: Sixty Years On the Jazz Scene, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2010, 111–112, 219–220.

- Himmelstein, David. Liner notes to Lucky Strikes, Prestige LP 7365, December 1964.

- Horricks, Raymond. “Lucky Thompson: A Jazz Musician Without a School,” Jazz Monthly 1/11 (January 1956), 6–8.

- Jones, Max. “Lucky Thompson Is Still Fighting the Vultures,” Melody Maker, September 5, 1959, p. 10.

- Jones, Max. Talking Jazz, New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1987, 72–78.

- Korall, Burt. “Lucky’s Back In Town,” Down Beat 30/15 (July 4, 1963), pp. 16–17.

- Morgenstern, Dan. “Recorded Jazz,” in The Oxford Companion to Jazz, New York: Oxford University Press, 2000, 783.

- Morgenstern, Dan. Liner notes to Lucky Thompson Plays Jerome Kern and No More, Moodsville 39, April 1963.

- Morgenstern, Dan. “Lucky Thompson Says Later for the Music Business,” Down Beat 33/1 (January 13, 1966), 11.

- Powers, Will. “Lucky Thompson,” Coda Magazine, 11/10 (July 1974), 36–37.

- Ruff, Willie. A Call To Assembly, New York: Penguin Books, 1991, 368–369, 377.

- Schoenberg, Loren. Liner notes to Lucky In Paris, HighNote HCD 7045, 1999.

- Watrous, Peter. “The Elusive Lucky Thompson,” Village Voice, June 26, 1984, 74.

- Watson, Michael D. “Lucky Thompson: A Survey of His Work On Record, Part 1,” Jazz Journal International 44/4 (April 1991), 20–22.

- Watson, Michael D. “Lucky Thompson: Michael D. Watson Concludes His Survey of Thompson’s Recorded Work,” Jazz Journal International 44/5 (May 1991), 14–15.

- Wilmer, Valerie. “Lucky Thompson Talks To ‘Jazz Monthly’,” Jazz Monthly 8/7 (September 1962), 12–15.

Discographical Sources

- Cohen, Noal. Online discography of Lucky Thompson, http://www.attictoys.com/jazz/LT_intro.html

- Edwards, David & Callahan, Mike. The Candid Label Album Discography: http://www.bsnpubs.com/cadence/candid.html

- Fitzgerald, Michael & Burgess, Brian W. Candid Records Listing: http://www.jazzdiscography.com/Labels/candid.htm

- Salemann, Dieter. Roots of Modern Jazz - The Be Bop Era Vol. 13: Solography, Discography, Band Routes, Engagements of Eli ‘Lucky’ Thompson 1943-1950, self-published, Berlin, Germany, 2001.

- Weir, Bob. Lucky Thompson Discography, Names & Numbers, Almere, The Netherlands, 2010.

- Williams, Tony. Lucky Thompson Discography, Part One, 1944-51, self-published, London, 1967.

Notes

[1] This introductory section is adapted from: Noal Cohen, Liner notes to Lucky Thompson New York City, 1964-65, Uptown UPCD 27.57/27.58, 2009.

[2] Although most sources indicate that Thompson was born in 1924, June 16, 1923 is the date he provided on his SS-5 form (application for Social Security number) in 1941. The authors have not obtained a copy of his birth certificate.

[3] Tad Shull, “When Backward Comes Out Ahead: Lucky Thompson’s Phrasing and Improvisation,” Annual Review of Jazz Studies 12 2002, (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2004), 63–83.

[4] The Avant-Garde, Atlantic Records, June and July 1960.

[5] Nat Hentoff, “Lucky Thompson: In Which an Underrated Musician Talks Strongly About the Seamier Side of Jazz,” Down Beat 23/8 (April 4, 1956), 9.

[6] Darryl Thompson (Lucky Thompson’s son) interviewed by Noal Cohen, February 11, 2008. After Thompson’s wife, Thelma, died at the end of 1962, he was the main caregiver to his sons Darryl and Kim.

[7] Christopher Kuhl, “A Visit With ‘Lucky’ Thompson,” New Arts Review, December 1981, 13-16.

[8] Marcus Printup, “The Insider: A Lucky Awakening,” Down Beat 73/5 (May 2006), 22.

[9] “Old Reliable” was issued on ABC Paramount 111, Lucky Thompson Featuring Oscar Pettiford, Vol. 1; “Seeing Is Believing” was issued on the very rare LP Club des Amateurs du Disque 3.001, Lucky Plays for the Club. “Down the Stretch” and “Check Out Time” were part of a French television show that took place on May 28, 1960, predating the NDR Workshop, but never issued commercially until very recently made available for download by the INA (see note 11).

[10] See http://www.candidrecords.com/.

[11] Several videos of Lucky Thompson, including the one with Solal, are available for download from the INA website: http://www.ina.fr/.

[12] Mark Gardner & Alan Bates, liner notes to Lord, Lord, Am I Ever Gonna Know?, Candid CCD 79035, 1997.

[13] This is the complete, unedited transcript of Lucky Thompson’s spoken statement from the CD and differs from that published in Mark Gardner’s 1969 Coda Magazine article.

[14] Archival records of the five NDR Jazz Workshops on which Lucky Thompson is present were obtained in 2006 from the NDR via discographer Uwe Weiler to whom we are most grateful.

[15] For the program from this four day tribute, see: http://www.attictoys.com/jazz/LT_Tribute.html.

[16] Recordings of the NDR Jazz Workshops on which Lucky Thompson is present were obtained in 2006 from collector Ronald Lyles to whom we are indebted.

[17] For a complete list of Lucky Thompson’s compositions see: http://www.attictoys.com/jazz/LT_comps.html.

[18] John Hicks interviewed by Chris Byars, March 22, 2006.

Author Information:

Noal Cohen is a jazz historian and co-author with Michael Fitzgerald of Rat Race Blues: The Musical Life of Gigi Gryce (Berkeley Hills Books, 2002). His website http://www.attictoys.com/ contains detailed discographies of several notable musicians including saxophonists Bob Mover, Lucky Thompson and Frank Strozier, vibraphonists Teddy Charles and Joe Locke, trombonist Benny Powell and pianists Elmo Hope and Carl Perkins. In addition to writing liner notes and book reviews, Cohen participates in and consults for educational programs in and around New York City.

Chris Byars was born in New York City to a musical family. His earliest exposure to music came as a performer on the stages of Lincoln Center opera companies. After switching his artistic focus to jazz in his teenage years, he has since pursued a career as saxophonist and arranger/composer. Winner of the Tanne Foundation Award and three Chamber Music America grants for education and composition, he combines a study of Lucky Thompson, Freddie Redd, and Gigi Gryce with a deliberate thrust towards creation of new sounds in jazz. His next CD, entitled Lucky Strikes Again, will be released on SteepleChase Records in April 2011. Since 2007, Byars spends an average of three months per year touring with bassist Ari Roland in conjunction with the U.S. Department of State, conducting cultural exchange programs in the Middle East, Central Asia, and the Balkans. In Cyprus, the Chris Byars/Ari Roland Jazz Futures program is in its third year, providing an artistic bridge across the long-standing political divisions of the island.

Abstract:

In the spring of 1961, saxophonist Lucky Thompson led a notable quartet recording session for the Candid Records label in Paris. The history of this session and the details of how it was eventually issued in its entirety over thirty years later are described. In addition, the eight intriguing Thompson compositions and their performances at the session are analyzed.

Keywords:

Lucky Thompson, Candid Records, NDR Jazz Workshop, jazz

How to cite this article:

- Chicago 15th ed.: Cohen, Noal and Chris Byars “Lucky Thompson In Paris: The 1961 Candid Records Session.” Current Research in Jazz 2, (2010).

- MLA 7th ed.: Cohen, Noal and Chris Byars “Lucky Thompson In Paris: The 1961 Candid Records Session.” Current Research in Jazz 2 (2010). Web. [date of access]

- APA 6th ed.: Cohen, N. and C. Byars (2010). Lucky Thompson In Paris: The 1961 Candid Records Session. Current Research in Jazz, 2. Retrieved from http://www.crj-online.org/

For further information, please contact: