History and Analysis of “Autumn Leaves”

Philippe Baudoin

Introduction

[This article is a revised portion of a larger work that will be published as Encyclopedia of 2500 Jazz Tunes — A Thematic, Historical, Musicological, and Discographical Catalogue.]

“Autumn Leaves” is the most important non-American standard. It has been recorded about 1400 times by mainstream and modern jazz musicians alone and is the eighth most recorded tune by jazzmen, just before “All the Things You Are”. [1] It was a chart hit in both Europe and America and has made regular appearances in films over the years. The composition has an interesting history that can be traced through the various published versions, and its oft-studied musical structure has ties to classical compositions.

History

“Les feuilles mortes” (literally ‘The Dead Leaves’) was originally a melody composed by Joseph Kosma [2] as a pas de deux (choreographed duo) for the ballet Le Rendez-vous, with a plot by Jacques Prévert. [3] It was introduced by Roland Petit in 1945, without words. The copyright is dated February 27, 1946 and it was first published by Enoch (Paris, France) in 1947.

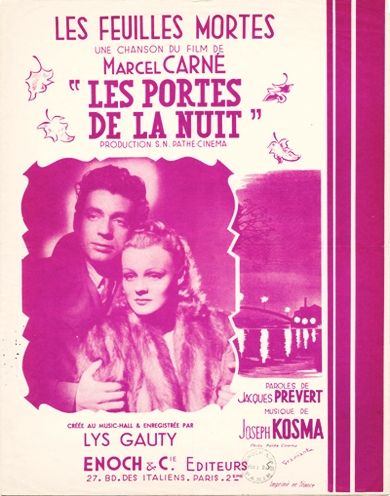

Figure 1. First sheet music with words.

Marcel Carné decided to use it in his film Les portes de la nuit and wanted it sung by Marlene Dietrich — who declined. In the movie, it is played by the whole orchestra, then by a harmonica, then hummed and sung briefly by Yves Montand, then sung by Irène Joachim (dubbed for actress Nathalie Nattier), and finishes as a waltz played by the whole orchestra. [4]

The memorable French lyrics (“C’est une chanson qui nous ressemble...”), written by Jacques Prévert, are those of a true poet. Singer Cora Vaucaire was the first to sing it in public. For four years, Yves Montand, whose name is invariably linked to the song, sang it with no success whatsoever; only in 1953 did he make it popular. Since then, the song has been adapted into countless languages and sung by a wide variety of artists, ranging from pop and rock singers to jazz musicians, while not being overlooked by classical performers such as Placido Domingo and trumpet virtuoso Maurice André. It took some time, however, for it to become a hit in America.

Figure 2. Dutch sheet music.

Michael Goldsen, who was in charge of Capitol’s music publishing department, fell in love with this song and, in 1950, asked the great Johnny Mercer to write the English lyric (“The falling leaves drift by the window...”). Mercer agreed — and soon forgot about it. Goldsen recalls:

I waited a couple of months. Finally it had, like, three weeks to go, and no lyric. I said, ‘Hey, John, I’ve only got three weeks to go and I lose the song.’ He said, ‘I’m going to New York on Friday. I’ll write it on the train and send it to you from New York. You’ll have it within a week. Pick me up and take me to the train station.’ They lived on De Longpre. I was delayed. I was fifteen minutes late, but we had time. I saw Johnny on the porch, and he’s nailing something to the door. I said, ‘Hey, John, I’m sorry I’m late, but we’ve got plenty of time.’ He said, ‘I thought maybe you had an emergency. While I was waiting, I wrote the lyrics.’ We got into the car and he read me the lyric. Tear came to my eyes. Everybody I played that song for flipped out. [5]

Mercer later told Michael Goldsen that he made more money from “Autumn Leaves” than from any other song that he wrote. [6] The sheet music (published by Ardmore Music, New York, N.Y. in 1950) and record sales kept “Autumn Leaves” in the first place slot of the television show Your Hit Parade for sixteen weeks in 1955.

Musical Analysis

Over the years since its first publication, the composition has undergone several adjustments. The verse is a 24-bar AA'B form, though originally it was written in twelve bars. The AA'BC form chorus was originally written in sixteen bars, but is now commonly seen as a 32-bar structure. The tune is usually played in 4/4 at a medium tempo in the key of G minor, although the original edition is in A minor.

The following analysis adopts the usual G minor key. The chorus melody spans a minor tenth and starts (A and A' sections) with a four-note ascending motif — three steps and a fourth (G A B♭ E♭). This pattern is then repeated three times, forming a descending sequence in stepwise motion.

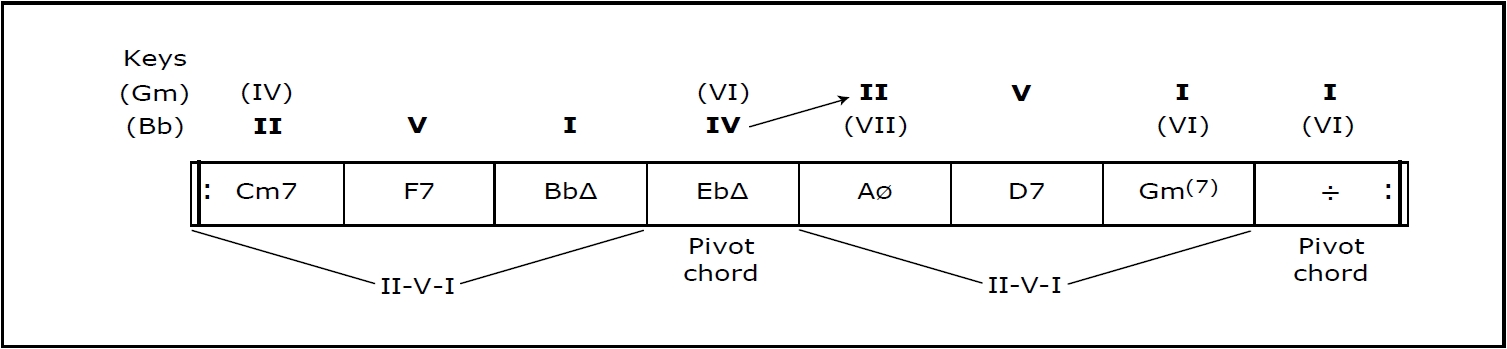

The piece is built on exemplary harmonic progressions and is often analyzed and played in jazz schools. Verse and chorus use only two keys: G minor (the main key) and B-flat major.

The chorus is one of the rare themes starting in the relative major of the ending key which is in minor (the opposite is very common). In the A and A' sections, a ii — V — I in B-flat major is followed by a ii — V — i in the relative minor (G minor). In the B section, the process is reversed.

Below I have made a chord analysis showing the perfect harmonic balance in the first eight bars: the pivot chords help in getting a very smooth modulation on bars 4–5, and 8–9 (when coming back to the second A section).

Figure 3. “Autumn Leaves”, A section analysis.

A study of the earliest printings of “Les feuilles mortes” reveals some astonishing things:

The first sheet music, a large format one, features on the cover Yves Montand and Nathalie Nattier in Les portes de la nuit (fig. 1, above). The couplet (verse) and the chorus are in A minor. The 24-bar verse is in 6/8.

Example 4. “Les feuilles mortes”, verse.

The big surprise comes with the chorus: it does not start with a three note anacrusis, but instead the melody begins after the first beat of the first bar!

Example 5. “Les feuille mortes”, chorus.

So, to achieve a proper ending, the composer had to insert a 2/4 measure before the final four-bar section, thus extending the tune to sixteen and a half bars!

In the first four-bar section of this version we find this chord progression (here transposed to G minor):

| Gm — Cm | F7 — B♭ | E♭ — Ami7♭5 | D7 — Gm |

This is hardly a new progression as it can be found exactly in Händel’s Passacaille in G minor, originally the last movement from his Harpsichord Suite in G minor (HMW 432), published in 1720. Chord symbols have been added to the first two lines.

Example 6. “Passacaglia in G minor”.

As Kosma studied composition and conducting at the Budapest Liszt Academy, he likely knew Händel’s piece. A similar progression can also be found later in the first movement of Mozart’s Sonata in F (K 332), published in 1784.

Kosma no doubt realized that his first writing of the chorus melody was a shaky one, with its odd 2/4 appendage. For the next printing, of small-format sheet music (fig. 7), he changed it, displacing the first three notes, which now became the anacrusis (fig. 9). This change was kept and from then on it works perfectly.

For the purposes of swing, the jazz musicians double the number of bars, playing the chorus as a 32-bar AA'BC form, usually in G minor. [7]

Figure 7. Later French sheet music.

Example 8. “Les feuille mortes”, verse.

Example 9. “Les feuille mortes”, chorus. Notice that in the first measure the wrong chord is named: Ré min. (D minor) instead of Ré7 (D7).

In this later edition, the verse is no longer in 6/8 but in 4/4 (fig. 8), the chorus is 16 measures long, and the entire tune is in E minor.

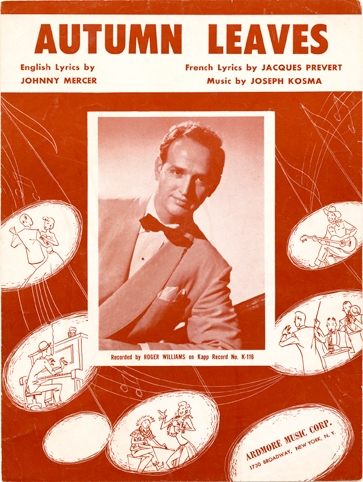

The same features can be found in my copy of the American sheet music published by Ardmore Music, with Roger Williams on the cover (fig. 10), but the verse is not included, as Johnny Mercer wrote no words for it.

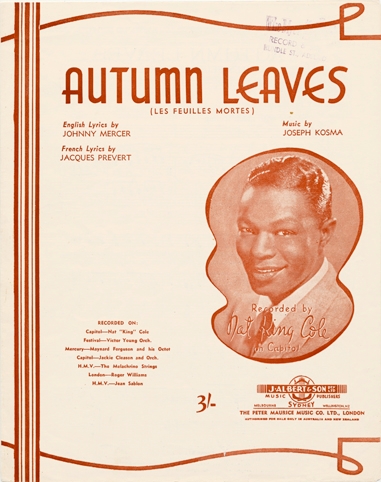

However, in the Australian version from J. Albert and Son (fig. 11), the verse does appear and its lyric is credited to Geoffrey Parsons.

Figure 10. American sheet music.

Figure 11. Australian sheet music.

In addition to its harmonic similarity to the earlier Händel and Mozart works, “Autumn Leaves” shares compositional characteristics with other later pieces. The chord structure of the first eight measures of the chorus is found in both “Are You Real?” (composed by Benny Golson in 1958) and “Alice In Wonderland” (composed by Sammy Fain in 1951) as played by Bill Evans in 1961. According to Marion Vidal and Isabelle Champion, “La Maritza”, a French song introduced by Sylvie Vartan, brought about a plagiarism suit based on its similarity to “Les feuilles mortes”; the plaintiffs won. [8]

Incidentally, the title “Autumn Leaves” is not unique. It is also the title of a 1856 painting by Sir John Everett Millais, now at the Manchester City Art Gallery, and a Danish death metal band (1994–2001) called themselves “Autumn Leaves.” There are also three earlier compositions that share this title: (Words and music by James E. Stewart © 1886; Music by Jacob Henry Ellis © 1905; Music by Charles Wakefield Cadman and words by Charles Dickens © 1925).

In 1962, French singer-author Serge Gainsbourg composed “La Chanson de Prévert” as an inspired tribute to “Les feuilles mortes”.

Appearances in Films

The song, originally written for the screen, was to be heard in almost a dozen films over the years.

- Introduced by Yves Montand, later by Irène Joachim (dubbed for Nathalie Nattier) in Les portes de la nuit (French, 1946).

- Sung again by Montand in Souvenirs perdus (French, 1950).

- Recurring theme of Autumn Leaves (1956), and sung by Nat King Cole under the closing credits.

- Sung by Louis Prima and Keely Smith in Hey Boy! Hey Girl! (1959).

- Played in The World of Benny Goodman (TV, 1963).

- Played by Chet Baker in Let’s Get Lost (1988).

- Played by Stéphane Grappelli in Addicted To Love (1997).

- Interpolated in Midnight In The Garden Of Good And Evil (1997).

- Played by Stan Getz in Sidewalks of New York (2000).

- The Cannonball Adderley recording is heard in The Score (2001).

- Performed by 101 Strings Orchestra in High Crimes (2002).

Recordings

The premier recording of “Les feuilles mortes” was by French singer Cora Vaucaire (January 1948, Chant-du-Monde) or perhaps by Jacques Douai in 1947, and the first jazz recording of “Autumn Leaves” was probably the one by Artie Shaw (October 5, 1950, Decca). An earlier recording of his (on September 13) was rejected. Two versions were hits in France, the first was in 1949 by Yves Montand, and the second was in 1950 by Juliette Gréco. In America, Roger Williams’s piano instrumental was a number one chart hit in 1955.

The piece was a favorite of jazz musicians Miles Davis, [9] Bill Evans, Harry James, Ahmad Jamal, Oscar Peterson, and Mel Torme. Among the many excellent jazz versions recorded over the years, some of the greatest are those by: Erroll Garner (1955), Cannonball Adderley, featuring Miles Davis (1958), Bill Evans (1959), Bobby Timmons (live in 1961), Miles Davis (live at Antibes in 1963), McCoy Tyner (1963), Eddie Louiss (1972), Wynton Marsalis (1986), Keith Jarrett (live in 1986). One oddity is a 1958 Duke Ellington live performance on which Ozzie Bailey sings the song in French.

The following list still does not approach completeness, as about 1400 different jazz versions exist.

- Cannonball Adderley 1958; 1960; 1963; 1966

- Nat Adderley 1990

- Jamey Aebersold 1989; 1991; 1995

- Toshiko Akiyoshi 1963; 1990

- Monty Alexander 1964

- Carl Allen 1989

- Henry Red Allen 1961; 1962

- Karrin Allyson 1996

- Franco Ambrosetti 1985; 2000; 2004

- Gene Ammons & Sonny Stitt 1961; 1961; 1973

- Louis Armstrong 1959

- Aurex Jazz Festival 1982

- Chet Baker 1974; 1977

- Kenny Ball 1999

- Patricia Barber 2000

- Joe Beck & Red Mitchell 1980; 1996

- Richie Beirach 1999

- Tony Bennett 1960

- Bob Berg 1990

- Warren Bernhardt 2001

- Acker Bilk 1989; 1993

- Cindy Blackman 1989

- Hamiet Bluiett 1986

- Stephano Bollani & Franco D’Andrea 2000

- Jean Bonal 1979*; 2000*

- Earl Bostic 1958

- Dee Dee Bridgewater 1992*

- Les Brown 1957

- Ray Bryant 1961; 1992

- Kenny Burrell 1991

- Don Byas 1967

- Conte Candoli 1957

- Benny Carter 1963

- Ron Carter 2002

- Hubert Clavecin (alias Gérard Gustin)/Stéphane Grappelli 1960*

- Buck Clayton 1963

- Arnett Cobb, Jimmy Heath, Joe Henderson 1988

- Al Cohn 1954; 1961

- Natalie Cole 1991

- Nat King Cole 1955; 1956; 1957

- John Coltrane 1962

- Chick Corea c1988; 2001

- Larry Coryell 1987 (with Miroslav Vitous); 2002

- Stanley Cowell 1990; 1993

- Wild Bill Davis 1956/1957

- Miles Davis 1960; 1960; 1963; 1964; 1964; 1964; 1964; 1966

- Joey DeFrancesco 2006

- Buddy DeFranco 1954; 1983; 1984

- Paul Desmond 1962; ?

- Niels Lan Doky 2000

- Kenny Dorham 1958; 1961

- Kenny Drew 1975; 1983; 1983

- Kenny Drew Jr 2001

- Anne Ducros 2005*

- Billy Eckstine/Benny Carter 1986

- Duke Ellington 1957; 1957; 1958; 1958

- Booker Ervin 1960

- Bill Evans 1959; 1960; 1960; 1960; 1961; 1965; 1969; 1969; 1969; 1972; 1972

- Tal Farlow 1955; 1977; 1991 (with Philippe Petit)

- Art Farmer 1959; 1983; 1986 (with Benny Golson)

- Maynard Ferguson 1955

- Boulou Ferré 1986

- Rachelle Ferrell 1989/1990

- Clare Fischer 1970; 1975

- Tommy Flanagan 1978 (with Hank Jones); 1980

- Jimmy Forrest 1961

- Four Seasons 1983

- Don Friedman 2006

- Curtis Fuller 1961

- Vyacheslav Ganelin 1978

- Hank Garland 1965

- Red Garland 1974; 1977

- Erroll Garner 1955; 1963; 1966

- Stan Getz 1952; 1975; 1980; 1980

- Terry Gibbs 1966

- Dizzy Gillespie 1957; 1957; 1971

- Benny Golson 1959; 1962

- Benny Goodman 1967

- Stéphane Grappelli 1960s*; 1971; 1977

- Johnny Griffin 1978

- Steve Grossman 1985

- Roger Guérin 2003*

- Jim Hall & Ron Carter 1972

- Chico Hamilton 1960

- Scott Hamilton 1993

- Lionel Hampton 1989

- Slide Hampton 1959

- Tom Harrell 1999

- Hampton Hawes 1967; 1968; 1968; 1968; 1968

- Hampton Hawes & Martial Solal 1967/1968

- Coleman Hawkins 1957; 1962

- Louis Hayes 2006

- Tubby Hayes 1959

- Vincent Herring 1993

- Eddie Higgins 2006

- Terumasa Hino c1960s; 1989

- Johnny Hodges 1961

- Ron Holloway 1993

- Freddie Hubbard 1992

- Bobby Hutcherson 1983

- Milt Jackson 1964

- Willis Jackson 1980

- Ahmad Jamal 1955; 1958; 1961; 1981 (with Gary Burton); 1994

- Harry James 1953; 1954; 1954; 1955; 1956; 1962

- Keith Jarrett 1986; 1994; 2002

- JATP 1954; 1975

- Jazz Modes 1956

- J.J. Johnson 1963; 1982; 1988*

- Hank Jones 1976; 1980; 1981; 1988; 2002

- Thad Jones 1975; 1977 (with Mel Lewis)

- Duke Jordan 1983; 1990

- Stanley Jordan 1989; 1990

- Wynton Kelly 1961; 1966

- Stan Kenton 1951; 1951

- Barney Kessel 1959; 1968; 1969

- David Kikoski 2008

- Lee Konitz 1968; 1974; 1988 (with Enrico Pieranunzi); 1993

- L.A. Four 1976

- Bireli Lagrene 1982; 1992; 1993

- Michel Legrand 1950s; 1974*; 1992

- Al & Stella Levitt 1988

- John Lewis & Albert Mangelsdorff 1962

- David Liebman & Franco D'Andrea 1989

- Limelight Dance Orchestra 1988

- Charles Lloyd 1966

- Didier Lockwood 1979

- Eddie Louiss 1972; 1994 (with Michel Petrucciani)

- Mike Mainieri 1968

- Manhattan Jazz Orchestra 1989

- Manhattan Jazz Quintet 1986; 2008

- Herbie Mann 1960; c1960s

- Charlie Mariano 1963; 1991

- Wynton Marsalis 1986; 1986

- Les McCann 1967

- Bobby McFerrin & Chick Corea 1990

- Helen Merrill 1967; 1988

- Red Mitchell 1982; 1990

- James Moody 1951*; 1963; 1973; 1987

- Frank Morgan 1956

- Lewis Nash 2008

- Oliver Nelson 1970

- Joe Newman 1977

- NHOP 1977

- Marty Paich 1960

- Joe Pass 1973; 1989

- Bernard Peiffer 1958

- Art Pepper 1960

- Oscar Peterson 1955; 1960; 1961; 1965; 1972; 1973 (with Stéphane Grappelli); 1974 (with Dizzy Gillespie); 1975 (with Jon Faddis)

- Michel Petrucciani 1985

- Enrico Pieranunzi 2001

- Jean-Michel Pilc 2003

- Louis Prima 1957

- Rodolphe Raffalli 2008*

- Jimmy Raney 1974; 1976

- Howard Roberts 1966

- Gonzalo Rubalcaba 1991

- Sauter-Finegan Orchestra 1954; 1957; 1957

- Larry Schneider 1992

- Diane Schuur 2001

- Shirley Scott 1960; 1991

- Bud Shank 1962

- Artie Shaw 1950; 1954

- George Shearing 1955; 1960

- Matthew Shipp 1997

- Zoot Sims 1961; 1984

- Frank Sinatra 1957

- Jimmy Smith 1956; 1981 (with Eddie Harris)

- Johnny Smith 1959; 1960

- Johnny Hammond Smith 1959; 1961

- Martial Solal 1960s*; 1976 (with NHOP)

- Sonny Stitt 1962/1963; 1963; 1980

- Gabor Szabo 1966

- Jack Teagarden 1958

- Jacky Terrasson 2002

- Clark Terry 1976; 1977; 1988

- Toots Thielemans 1975; 1976; 1980; 1986; 1986

- Jesper Thilo 2006

- Sir Charles Thompson 1993; 2001

- Bobby Timmons 1961

- Cal Tjader 5; 19614

- Mel Torme 1956; 1957; 1982; 1990; 1991 (with Cleo Laine)

- McCoy Tyner 1963; 1988

- René Urtreger 2005

- Maurice Vander 1959

- Sarah Vaughan 1982

- Joe Venuti 1950s; 1952/1953; 1954; 1969; 1976

- VIP Trio 1988

- Mal Waldron 1981

- David S. Ware 1992

- Julius Watkins 1956

- Benny Waters 1981; 1983; 1993

- Ben Webster 1965 (with Kenny Drew); 1972; 1973

- George Wein 1969

- Kenny Werner 1994

- Paul Whiteman 1956

- Putte Wickman 1969; 1977

- Barney Wilen 1987*; 1989; 1994

- Cassandra Wilson & Jacky Terrasson 1997

- Jessica Williams 1989; 1994

- Joe Williams 1962

- Mary Lou Williams 1979

- Kai Winding 1961

- Louis Winsberg 1989

- Phil Woods 2000

- Larry Young 1963

Versions followed by an asterisk (*) are entitled “Les feuilles mortes”; all others are entitled “Autumn Leaves”.

References

[1] Composer Joseph Kosma (Kozma József, born October 22, 1905, Budapest; died August 7, 1969, La Roche-Guyon, France) went to Paris in 1933. He was successful as composer for the movies (Jean Renoir, Marcel Carné), and as popular songwriter, especially when associated with lyricist Jacques Prévert (this team was “la crème de la crème” of the “chanson rive gauche — St. Germain des Prés”). Kosma also composed several classical works.

[2] Jacques Prévert (born February 4, 1900, Neuilly-sur-Seine; died April 11, 1977, Omonville-la-Petite) was a famous French lyricist, poet, and scenario writer.

[3] It can be heard on the first volume of the Intégrale Yves Montand 1945-1949 FA 199, Frémeaux & Associés.

[4] Gene Lees, Portrait of Johnny: The Life of John Herndon Mercer, New York, Pantheon Books, 2004, 215–16.

[5] Ibid., 216.

[6] A jazz version (music and words) can be found in The New Real Book: Jazz Classics, Choice Standards, Pop Fusion Classics, Petaluma, CA: Sher Music, 1988.

[7] Marion Vidal and Isabelle Champion, Chansons du cinéma, Paris, M.A. Editions, 1990, 108.

[8] Davis had a love affair with Juliette Gréco (see fig. 7) in Paris in 1949, the very year when she recorded “Les feuilles mortes”. Could this explain why Davis favored the tune, and repeatedly played it between 1958 and 1966?

Author Information:

Philippe Baudoin is a French jazz pianist, arranger, author of historical and musicological works, record producer, and historian. Co-leader of the successful Anachronic Jazz Band, Baudoin is a teacher at CIM music school in Paris, in several Paris conservatories, and he was course director of “Histoire et techniques du jazz” at the Sorbonne and the Cité de la musique. He took part in Alain Resnais’s 1991 film on George Gershwin both on-screen and as music consultant. A member of the Académie du Jazz, he is an avid collector of sheet music and jazz documents and is a specialist on jazz repertoire.

Abstract:

Judging by the number of times it has been recorded, “Autumn Leaves” is the most important non-American standard in the jazz repertoire. This article traces the composition’s interesting history through the various published versions, and shows how its oft-studied musical structure has ties to classical compositions.

Keywords:

Autumn Leaves, Joseph Kosma, Jacques Prévert, Johnny Mercer

How to cite this article:

- Chicago 15th ed.: Baudoin, Philippe. “History and Analysis of ‘Autumn Leaves’.” Current Research in Jazz 4, (2012).

- MLA 7th ed.: Baudoin, Philippe. “History and Analysis of ‘Autumn Leaves’.” Current Research in Jazz 4 (2012). Web. [date of access]

- APA 6th ed.: Baudoin, P. (2012). History and Analysis of “Autumn Leaves”. Current Research in Jazz, 4 Retrieved from http://www.crj-online.org/

For further information, please contact: