Treemonisha, or Der Freischütz Upside Down

Marcello Piras

A Musical Ancestry Quest

The opera lover listening to Porgy and Bess for the first time cannot help being struck by its opening gesture — a majestic musical curtain riser, as well as a deliberate bow to another work on race relationships, Giuseppe Verdi’s Otello. This is far from exceptional. Virtually every opera is related to one or more earlier ones; if it sounds radically original, it is usually because its reference models happen to be obscure. Pergolesi’s La serva padrona has come to us, Tomaso Albinoni’s Pimpinone has not, yet libretto comparison shows how the former descended from the latter.

As we approach an isolated masterpiece like Scott Joplin’s Treemonisha, the ancestry enigma grows fascinating. Joplin himself seems to come out of nowhere — a slave descendant from a nameless place in the midst of nowhere, grown in a newborn town, far removed from cultural centers, let alone from the glittering bel canto world. How could he gather the required knowledge? How did he become imbued with the genre code and learn the tricks of the craft that make a composer an opera composer?

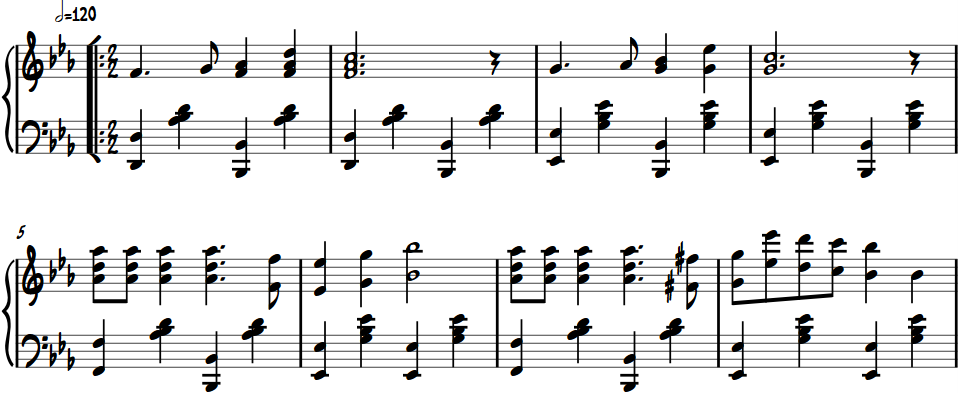

Not that the score itself offers no clue. On the contrary, there are too many to deal with them all in one essay. A few have been found by earlier scholars. The first was perhaps Gunther Schuller, who made specific orchestration choices after identifying source passages from the standard opera repertoire. Here is an example he told me in conversation, when we were teaching in Palermo (1998). Joplin’s model here is, of all things, Giuseppe Verdi’s Don Carlos. The opening bars from “Good Advice” show a marked resemblance to the low brass fanfare preceding Élizabeth’s air, Toi qui sus le néant des grandeurs de ce monde, with its “bluesy” ambiguity; and Schuller scored them accordingly.

More recently, Theodore Albrecht devoted a study [1] to identifying various sources of Joplin’s opera. In the present essay, conceived before reading his, [2] I shall agree on some of his findings. Hence, these can count as independent confirmations. The main difference between the two studies is the following: I stress that such relationships work at various levels, some superficial (e.g., a quotation), some structural. After all, a composer, before quoting or drawing from single passages, has to plan the whole show. Joplin’s first step was writing down a libretto, thus facing literary choices: What story? On what scale? How many characters? What distribution of events among the acts? And, most important: an opera to say what?

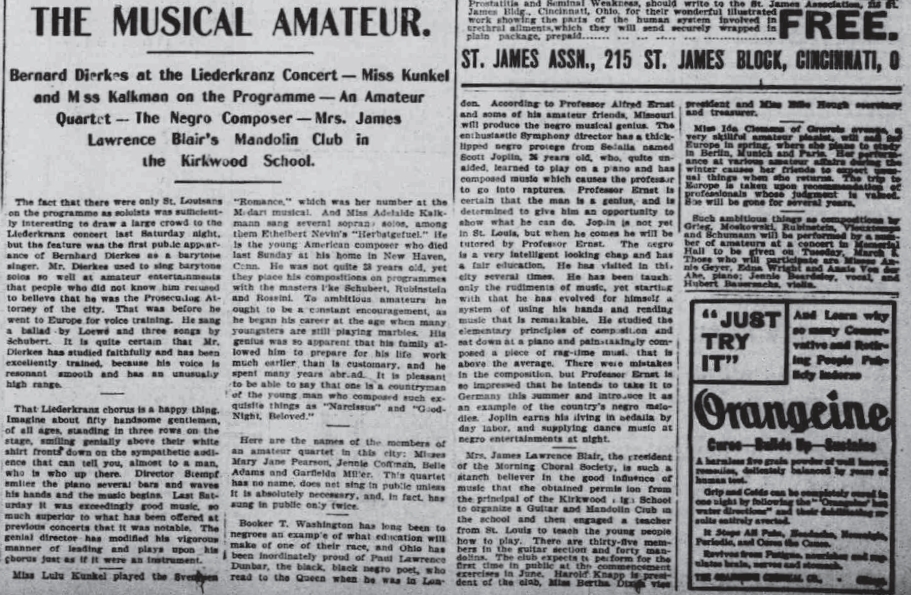

An often echoed opinion suggests that Wagner — another composer who set his own words to music — was Joplin’s role model. Reasons to think so boil down to three facts: (1) Joplin heard Wagner’s music in a documented circumstance; (2) he had a German music teacher; and (3), there is a sacred tree in Die Walküre. Actually, that very incident proves the opposite: in 1901, Joplin was surprised by Wagner’s music, clearly unknown to him. Its serpentine chord sequences, eschewing fixed bar numbers and expected turning points, were light-years distant from his musical language, nor is any convergence perceivable after that date. (Admiration does not imply imitation.) For this same reason — plus another I shall deal with later on — the sacred tree in Die Walküre proves little on the one in Treemonisha, as long as its sacredness remains unexplained. The world out there is full of trees.

The only solid piece of evidence here is the German teacher, Julius Weiss. All that has been known so far on this elusive figure [3] can be summarized in a paragraph. Born in Saxony by 1840–41, perhaps of Jewish ancestry, Weiss probably graduated by 1860 and migrated by the late sixties. About a decade later, a wealthy Texarkana man, Colonel Robert W. Rodgers, hired him as private tutor for his sons and daughters, to whom Weiss taught music, German, and scientific matters. By that time, Weiss met Joplin, then a child, and gave him lessons, unfolding new horizons before his eyes. Weiss was fond of opera and passed such love on to his pupil, who was forever grateful, to the point of financially helping him in his late years, which he seems to have spent in Houston in poverty.

As such information is poured into Joplin biographies, it could suggest the following scenario: as a child, he stumbled upon a German music teacher and fell in love with opera. By the same token, he might meet a French chef and become a cook, or a Japanese coach and embrace ju-jutsu. Here we see how first-rate research may end up being framed into a widely shared ideology which goes unnoticed. The underlying myth is “Individuals are all,” also known as, “There is no such thing as society.” Thus, Joplin’s love of opera was the result of random incidents.

Now, random incidents do occur. However, when placed in context, they take on a meaning.

Context I: German Culture in Nineteenth Century USA

Today, some fifty million Americans boast German ancestry. Immigration started by 1680 and soon gave birth to all-German neighborhoods and the introduction of specific musical usages. The earliest example, albeit perhaps not very typical, is probably Georg Conrad Beissel’s Ephrata community in Pennsylvania, founded in 1732 and soon capable of producing notated a cappella settings of Biblical texts in German.

In eighteenth-century English- and German-speaking Europe, choirs were mainly confined to churches and public ceremonies, thus eliciting a rich production of masses, motets, oratorios, and cantatas. Then, as a result of the widespread secularization that followed the French Revolution and Napoleon, the nineteenth century saw a boom of private choral clubs, spreading in inverse ratio to the shrinking role of church music. The start-up had come from German-speaking musicians, in particular Johann Adam Hiller, who conducted Händel’s Messiah to wide acclaim in 1786, and Carl Fasch, who founded the Berlin Singakademie in 1791, primarily to promote Bach’s music; in 1800, as Fasch passed away, Carl Friedrich Zelter took over. The Singakademie probably originated from an earlier Singethee, a sort of drawing-room social meeting, in which people drank tea, had conversation, and sang.

These trailblazing examples promoted lofty aesthetic ideals — resurrecting past masterpieces, as well as challenging the perceived involution in popular musical tastes. However, they inspired endless imitations at all levels, from excellent professional outfits down to neighborhood glee clubs. German men rushed to gather in associations, often called Singvereine; especially at the onset, it was an all-male affair. They enjoyed the pleasures of collective music-making, indulging in conversation on philosophy and politics, and being replenished with beverages, tea having quickly been replaced by beer. An example, again with Zelter behind it, was the Berlin Liedertafel (1809). Also, in 1800, a municipal Musikakademie was founded in Düsseldorf, triggering a cascade of similar organizations in the Lower Rhine area. There, municipalities secured generous financial support, making it possible to stage huge inter-city festivals, emulating a venerable English formula (the Three Choirs Festival) and soon reaching mammoth sizes. The earliest Sängerfest was perhaps the one held in Hambach, Bavaria, in 1830 or 1832. [4]

What did those people sing? The “back-to-old-masters” goal was never dropped, but the repertoire was expanded and updated; the classics — Bach and Händel, Gluck and Mozart, Beethoven and Cherubini — increasingly shared the bill with Schubert, Weber, Marschner, Mendelssohn, and Schumann. This practice was widespread, and just one German émigré could be enough to found a Singverein anywhere, as Ludwig Landsberg, for instance, did in Rome in 1838. [5]

Also, Jews were involved in the movement right from its start. The earliest members of the Berlin Singakademie include names from both major Jewish musical dynasties, the Mendelssohns and the Itzig/Bartholdys. An uninterrupted record of Jewish presence follows.

Migration to America transplanted the whole movement to the USA. Germans crossed the ocean for many reasons: some pioneers, such as Beissel, sought virgin ground to build utopian communities shaped along their eccentric religious views; others were just peasants in need of land. In the 19th century, land remained a major goal; religious utopia yielded to political utopia.

Texas is a fine example. Friedrich Ernst, the “Father of German Immigration to Texas,” settled in the early 1830s; his lyrical depiction of Austin County prompted a massive flow of migrants. In 1842, Prince Carl of Solms-Braunfels and other noblemen founded the Verein zum Schutz deutscher Einwanderer in Texas, organizing land distribution to newcomers. Peasants these were for sure, yet as early as 1834 one Robert Justus Kleber imported a piano and some music books to Harrisburg (now part of Houston); notated music practice soon took a foothold. [6]

Much the same happened in Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, or the St. Louis, Missouri area. Phillip Matthias Wohlseiffer founded the first German-American choral society, the Philadelphia Männerchor, in 1835; the following year he founded the Baltimore Liederkranz. Similar associations, soon hosting women as well, appeared in many cities and towns. The natural next step was a Sängerfest, held in March 1846, when Wohlseiffer’s two organizations paid each other visit. A replica of the German model had been built in New England in a mere eleven years.

Texas followed the same pattern as well. First, informal vocal groups; then a Singverein, probably in San Antonio, soon emulated in other cities; and finally, in 1853, the San Antonio, New Braunfels, Austin, and Houston choirs joined for a Sängerfest and founded an association of associations, the Texas State Sängerbund.

Given the distances, the process never coalesced into a unified national federation. Rather, several local circuits had simultaneous origin and growth. The Nord-Amerikanischer Sängerbund was born in Cincinnati in 1849; New England had its own Nordöstlischer Sängerbund from 1850. As a result, any mid-century German immigrant could find employment, or spend some leisure time, as teacher, singer, vocal coach, accompanist, conductor, transcriber, or composer in many American cities, and even jump from circuit to circuit. This is what Julius Weiss was to do — with a twist.

Of course, a difference between German and German-American choral activity was, the latter was also meant to reinforce a sense of national identity abroad. Most Romantic art carries national overtones, and German music was second to none in that respect. In particular, Carl Maria von Weber’s masterpiece, Der Freischütz, the “national German opera” par excellence, with its folk-tale plot, folk characters and beliefs, folk dances and choirs, folk scenarios and costumes, must have struck a deep chord in many hearts. Its first performance in the USA took place, in English, at New York’s Park Theater, on March 2, 1825, only four years after Weber had conducted its première in Berlin. Over the years, performances of the entire opera, or parts thereof, grew frequent in the USA, in both English and German.

The 1848–49 revolution, and the ensuing repression, brought another element into the scene. Students and intellectuals involved in the riots escaped abroad. Many sported progressive, even Socialist ideas. Karl Marx himself was one of them, except that he went to London, probably drawn to the British Library. Others headed to America, and their ideas of justice, equality, and social change swept the German communities. They are usually referred to as the Achtundvierziger (“Forty-Eighters”). [7] Let us name a few.

Adolph Douai (1819–1888), founder of the San Antonio Zeitung and editor of the Boston Demokrat, was a free thinker and a revolutionary, vigorously championing abolition, equality, and education for everybody as a mean to achieve social progress. An early member of the Socialist Labor Party of America, he was also a pioneer of the Kindergarten movement. Edgar von Westphalen (1819–1890) was Karl Marx’s brother-in-law; early in 1848 he went to Texas to help establish Communist settlements, such as the five Lateinische Kolonien (“Latin Settlements,” as people loved to have conversation in Latin): Bettina (named after Beethoven’s friend, Bettina Brentano von Arnim), Latium, Millheim, Sisterdale, and Tusculum. Westphalen then returned to Europe; in 1865 he spent few months at Marx’s home in London. Ferdinand Ludwig Herff, Hermann Spiess, and Gustav Schleicher founded the Gesellschaft der Vierziger (“The Society of the Forty”) also known as the Freidenker, the Darmstädter, or the Socialistic Colony and Society, which planned to create a community in Wisconsin and then opted for Texas. In 1878, Schleicher, by then turned into an old skeptical Republican senator, visited Texarkana; [8] Scott Joplin was eleven. Even the Frenchman Étienne Cabet (1788–1856), who coined the word “Communism,” tried to found his early-Christian-inspired Icarian community in Denton County, five counties west of Texarkana. As this turned impossible, he tried again in Nauvoo, Illinois. He died in St. Louis, Missouri.

These and other utopians who founded their — often short-lived — communes in Texas, Wisconsin, and elsewhere, held divergent views on many details, but shared an unshakable faith in the positive nature of humankind, in education as a tool to forge a better society, and in equality of all people, women included (albeit the last point was unevenly addressed). This is also the political vision Joplin expressed in Treemonisha, a work that can be properly labeled a “Socialist opera.”

Context II: Texarkana

Texarkana, too, is in Texas, or more accurately, half of it is (the rest is in Arkansas). Yet it is located at the extreme northeastern corner of the state, hundreds of miles away from the Central-Southern area hosting the German communities. In fact, as far as it is known, neither did it have a Singverein of its own, nor was it part of the Texas State Sängerbund circuit.

At least three contrasting local legends report that the Bowie County area on which it grew was referred to as “Texarkana” many years before anything was built. [9] The county was probably settled by 1820 and was given its borders in 1846. It was a rural, low-density area, with people raising livestock and producing cotton, corn, and timber. Before the war, its white inhabitants were mostly Southerners, slaves slightly outnumbering them. Of course they massively voted for Secession and fought for it. War, Emancipation, and the ensuing instability led many ex-slaveowners to bankrupt, unleashing widespread rage. The slim Federal garrison — a dozen people — sent in 1867 could do little to ensure legality; the infamous Cullen Baker, “the Swamp Fox of the Sulphur,” could rob and kill, probably sheltered for months by those who saw him as a vindicator. Klan-like activities were also registered. [10] Much the same also holds true about Cass County, south of Bowie, where Joplin’s family was living in 1870.

Then, enter the railroad. Its construction, suspended because of warfare, was resumed soon after and became a daily subject in Texas newspapers. Trains were an astonishing step forward over horse, ship, or steamboat. Coastal towns, such as Galveston, saw it as a safer alternative to seafaring, as it would reach Northern cities in any weather. Cities in the interior saw the station as a waterfront with no sea — a powerful source of work and business multiplier. The Reconstruction governments saw the train as a political unifier. Railroad cartographers selected an ideal site on the Texas-Arkansas state border, and Texarkana grew around it. [11] It was a station before being a city.

The locality was well chosen, being strategically placed, as it was, at the intersection of both East-West and North-South commercial routes, as the Caddo natives knew well. It was more than just connected to the German communities — it connected the rest of the nation to them. Newspapers issuing daily timetables, such as the Fort Worth Gazette, soon added the new stop.

Although some families were already living in the surroundings, Texarkana was officially born on December 8, 1873, when a George M. Clark opened a drug and grocery store cum whisky, and the Texas and Pacific Railroad began selling lots. [12] The combination of affordable land and up-to-date connections proved irresistible. Investors swarmed from all parts, and, almost overnight, Texarkana grew in both size and wealth. A paradoxical creature had materialized — a rich city in the middle of an impoverished countryside.

There was another deeper divide as well. The newcomers were ethnically much more diverse than the old county settlers, and carried no memories of local racial tensions. Some were wholeheartedly for integration, having personally suffered social injustice in their homelands. For instance, the Jewish community soon grew numerous; in 1879, a newspaper editor, Charles Wessolowsky, counted ten families (ca. seventy-five people) in town, who happened to have a synagogue but no rabbi. Most of them were born in Austria, Poland, and Russia; their last names were: Erber, Goldberg, Davidson, Hoffman, Kosminsky, Heilbron, Marx, Rosenberg, Levy, and Deutschmann. The last one was the very same Joseph Deutschmann who lived with Julius Weiss at Colonel Rodgers’ home. A Pole who worked in real estate, he also helped develop water, gas, and streetcar companies and, in 1885, became president of the Texarkana Hebrew Benevolent Association. [13]

In late 1874, a flood swept the black neighborhood. Deutschmann then rebuilt it and also constructed what was called Deutschmann’s Canal, to improve drainage. Its efficiency remains unclear though. The Houston Daily Post of January 15, 1899 reports:

TEXARKANA, Texas, January 13. The heavy rains that have visited this section recently have caused numerous washouts on the several railroads centering here.... The Negro portion of town known as “Swampoodle” is almost entirely inundated. Several shanties have been carried away by the water and much damage has been done. [14]

Did the Joplins live in Swampoodle? Researchers know that in 1880 their house was located on 618 Hazel Street. We can give it a look.

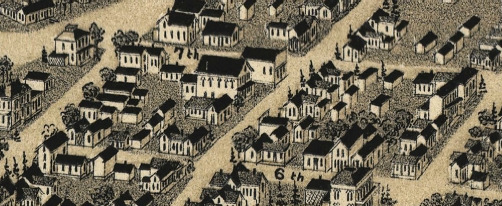

By 1888, the noted German viewmaker, Henry Wellge (1850–1917), drew a bird’s-eye view of Texarkana, now at the Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress. It is painstakingly accurate. Here is how the 600 blocks on the two sides of Hazel Street, between Sixth and Seventh, appeared to him:

Figure 1. Henry Wellge (1850–1917), Perspective Map of Texarkana. ca. 1888. Detail of the 600 blocks on the two sides of Hazel Street. [15]

Joplin came from the plantations around Linden, like T-Bone Walker fifty years later. The musical gulf between a cultivated opera composer and a rural blues singer-guitarist can be traced not only to Texarkana’s peculiar history, but also to Deutschmann’s progressive views. Without his vision, it is doubtful that freedmen could afford to relocate from country log cabins to more dignified city lodgings.

Context III: Julius’s Vice

Much has been said, mostly as speculation, about Joplin’s teacher, especially after Albrecht’s essay singlehandedly drew him out of his earlier legendary status. Much remains to be ascertained though. For instance, Albrecht could find nothing on Julius Weiss’s life in Saxony and speculated that he might have expatriated in 1866, to escape the Austro-Prussian war. Also, he deemed likely that Weiss “could also have entered the United States at New Orleans, a port through which many Germans immigrated.” [16] Perusal of immigrant lists on the Ancestry.com website showed that America was flooded with people named Julius Weiss, much to Joplin scholars’ dismay, yet none of those who landed in New York, Boston, or Philadelphia fits known data. Only one passenger fits, and he landed in New Orleans, as Albrecht had figured out, but in 1870 — a timely move in any case, with the Franco-Prussian War impending. Perhaps the man had served in the Saxon army in 1866 and decided that a taste of it was enough. The question remains unanswered, for such name recurs on lists of German soldiers as well.

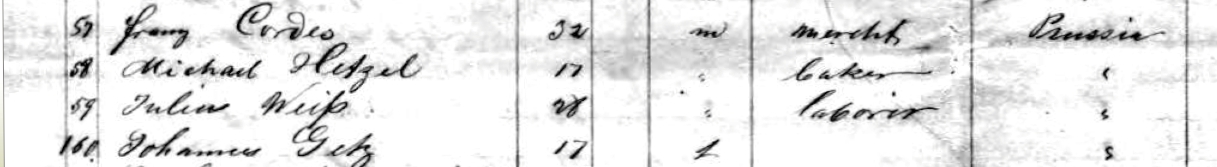

Be that as it may, one Julius Weiss sailed from Bremen by April 1870 on the Frankfurt, which made stops at Le Havre and Havana before reaching New Orleans on May 9. He is described as a 28-year-old male, laborer, from Prussia. In the 1880 Census, Weiss was recorded as being 39 on June 3. [17] A birthdate between late April and early June 1841 would match both documents.

Provenance is also in agreement. In the 1866 Austro-Prussian War, Saxony sided with Austria, lost, and was annexed to the newborn Norddeutscher Bund (North German Confederation), an entity that was to exist for just five years, as an intermediate step toward Germany’s unification under Kaiser Wilhelm. Hence, in 1870 Weiss was a citizen of — and was sailing from — the Norddeutscher Bund. This associated twenty-two states but was dominated by Prussia in all respects (surface, inhabitants, gross income, number of Parliament seats, army), thus, on the narrow column of a form, it was routinely indicated as “Prussia.” In the 1880 Census, Weiss could have said “Germany,” by now a valid tag, but was probably asked: “In which country were you born?,” and answered accordingly. As for the portmanteau “Laborer” entry, it may simply mean that he was emigrating to find a job; nothing is implied on his class status. See the line of passenger [1]59, second from below; surname is spelled Weiß.

Figure 2. List of passengers on the Frankfurt; detail including Julius Weiss’s name. 1870. [18]

As it often happened with immigrants, the destination port was no choice; ships just headed there. There is no evidence on the locality where Weiss lived in 1870–73. Then, one can choose among the multiple possibilities that newpaper citations offer. As ubiquity is ruled out and we cling to musically significant profiles, our man happens to resurface, of all places, in Port Jervis, Orange County, New York — a logical nearby place for somebody landing at New York, not in Louisiana. Did he soon sail from New Orleans up North, thus dodging the 1870 Census? But then, why did he not wait in Bremen for the next German ship heading to New York? Was he in a hurry? We do not know.

A small town on the Delaware River, Port Jervis hosted an ancient German community which, not surprisingly, had sported a Männerchor since 1867. The first of a long string of references to Julius Weiss in the local newspaper, the Evening Gazette, seems to be the one from April 23, 1874: “Mr. Weiss last Monday opened the school in the Lutheran church, for the German Lutheran children of this place.” [19] April 20 seems an odd date to open a school, unless it was brand new. So was the Singverein announced on September 5: [20]

The German residents of this village have organized a new singing society. It is called the Concordia, and meets in Germania Hotel. Its officers are, President, Leopold Fuerth; Vice President, H. Schroeder; Sec’y, F. Conzelman; Treas., Frank Hadrich, with Frank Weiss and Prof. Stuebinger, musical directors. [21]

The anonymous journalist wrote “Frank” Weiss in error, for this was the name of an older resident in town, but meant Julius, as it grows clear from later articles; again, this suggests that such name was new in town. Notice the presence of Prof. Stübinger at his side; more on him later.

On November 28, we can read a lengthy account of the activities of this second German vocal group in Port Jervis. It allows us a vivid glimpse on its proceedings.

CONCORDIA.

ORGANIZATION — THE MANNER IN WHICH SOME OF OUR DENIZENS HAVE RECREATIONS — THANKSGIVING RECEPTION.

“Concordia” is the name of an association lately formed in this village. It is composed of the most select of the Jewish and German residents of Port Jervis; is properly and well officered, has good and wise rules for its government, and is organized for the pleasure and social advancement of its members. They meet with their ladies every Wednesday evening. The early portion of the evening is devoted to music, vocal and instrumental, to speaking and exercise in oratory and reading from the works of eminent authors, to private theatricals, etc. The later portion of the evening is devoted to dancing.

The “Concordia” has been organized about 4 months and has now about 30 members. The officers are: Leopold Fuerth, President; Henry Schroeder, Vice President; F. Conzelman, Recording Secretary; P. Kalmus, Financial Secretary; Frank Hadrich, Treasurer; Julius Weiss, Musical Director. The dues are 25 cents a month, which go to pay for music, rent, etc. The society usually meets Sunday evenings for rehearsal, and the like. None but members and invited guests are allowed to be present.

The Concordia gave a reception and entertainment Thanksgiving night, and through the courtesy of the President and members of the association the representatives of the press of this village were invited to be present and participate in the festivities. Availing themselves of the opportunity Mr. C. St. John, Jr., editor, and Mr. Ed. Botsford, reporter on the Union, Prof. E. G. Fowler, of the Associated Press, and a representative of the GAZETTE establishment, attended the reception. The rooms were opened at 8 o’clock, at which time members and their lady friends began to arrive. Singing and instrumental music began. Mrs. Fuerth and Mrs. Silverstone played a two-handed [sic] piece on the piano, and later in the evening Mrs. Silverstone, who has a rich, clear voice, and is a fine singer, sang the “Merry Birds.” Miss Jenett Mertz also sang a pretty piece, executing it nicely. Prof. Fowler sang three songs, and his rich tenor voice sounded unusually clear and good. The professor certainly is an excellent singer. Mr. Louis Hensel, senior, repeated the first act in Faust, making a marked impression upon the audience. Mr. Hensel is really a clever actor, and the members of Concordia no doubt congratulated themselves that they have one so able among them. Prof. Stuebinger and Robert and William Schroeder aided with music at the piano. At the early part of the evening the latter declaimed two pieces from Hans Brenzman, a work in “Pennsylvania Dutch.” He did it creditably and elicited applause. Editor St. John wanted to sing a song. He gravely told the President that he had been under training in New York and had cultivated his voice so that it was remarkably musical. He offered to sing “Carry the News to Mary,” “Over the River to Charley,” “Jordan Is a Hard Head to Travel,” or “Pop Goes the Weasel.“ The musicians failing to urge the ambitious young man to test his musical abilities, he took offence and made faces at the Italian harpist. After repeating in an undertone the couplet, “This world is all a fleeting show, For man’s illusion given,” he silently sat down in a corner and waited for supper.

About 11 o’clock a collation was spread upon the tables, of which all partook heartily. After collation, the room was quickly cleared, and dancing followed. This was continued until after 3 o’clock in the morning, when all took their departure, highly gratified with the manner in which Concordia observed Thanksgiving Day. We hope the association will have many as pleasant gatherings. [22]

This clipping reveals that Joplin’s teacher totally belonged in the Singverein world. There, gentlemen — and sometimes ladies — peacefully gathered and had a good time playing, singing, listening, dancing, eating, and drinking. This is very much the ideal well-mannered environment Joplin evoked in The Ragtime Dance, the earliest known statement of his life philosophy. Also, in such gatherings, music coexisted with prose and poetry, from the high seriousness of drama down to comedy routines. Joplin, too, was to combine music, poetry, recitation, and drinks, not only in his proto-rap sequence from Pine Apple Rag Song, but already in his performances with the Texas Medley Quartette, as reported from New York in the Syracuse Daily Journal, September 13, 1894:

A musical and literary entertainment will be given by the Texas Medley quartet and the ladies of the Bethany Baptist church at the church in East Washington street this evening. After the concert refreshments will be served. [23]

In a town of few thousand souls, we find the same people collaborating to both organizations. Here is again the Evening Gazette, December 1, 1874:

THE GERMAN MANNERCHOR — THE COMEDY OF THE “WEDDING TOUR” — SUCCESS OF THE ORGANIZATION.

The German Mannerchor, an organization well and favorably known in this village, is now giving a series of comedies and theatrical plays at their fine rooms in Atlantic Hall. Last night the comedy of “The Wedding Tour,” in two acts, was well represented. The play is a German comedy representing the life of a professor of foreign and classic languages, who in some manner stumbles into the state of matrimony, and some of the mistakes he made thereafter.... The comedy was unquestionably well acted, and elicited frequent applause from the large German audience present. A good orchestra, composed of the following-named gentlemen, furnished music at proper intervals: Prof. S. Stuebinger, Prof. Julius Weiss, Mr. Adam Fetz, Mr. Jacob Gengnagle, and Master George Angermyer [sic]. At the close of this acting, the room was quickly cleared, and dancing followed.

The next play of the Mannerchor will take place in about 3 weeks, at their hall. The play is entitled: “Enlenspiegel.” [sic] He was an old German highwayman, who robbed from the rich and gave to the poor, and did many other eccentric things.... [24]

Apparently, the journalist had never heard of Till Eulenspiegel, the German prankster of folktales who was soon to be made famous musically in an 1895 Richard Strauss tone poem. Less apparent is whether such depiction, more suited to Robin Hood than to Till, was traceable to what the Männerchor members had said, or what was understood of their words, or the adaptation of the text they had concocted, or a mix thereof.

Over the years, Weiss gained stature and respect in the Port Jervis community. On July 23, 1877 he is reported to have taken part, the day before, at the funeral of a Mr. Jacob Pobe, buried with Odd Fellows honors.

....As the remains were being borne up the stairway into the hall the plaintive notes of a funeral dirge from Mendelssohn were heard from the organ. The music for the occasion was under the direction of the German Mannerchor, led by Prof. Julius Weiss, its accomplished leader, with organ accompaniment, and was most impressively rendered. Rev. H. M. Voorhees read a few appropriate passages of scripture, and the choir intoned the beautiful hymn “Da Unten ist frieden” with fine effect.

Rev. H. B. Kuhn, pastor of the Lutheran church, which the family of the deceased attended, preached a very interesting sermon from Deuteronomy 32d chapter and 39th verse.... After the sermon the reverend gentleman gave a brief history of the deceased and paid a fitting tribute to his memory. Many in the audience were moved to tears. Another hymn was then rendered by the choir, — “Suess und ruhig ist der Schlummer” — when the Rev. H. M. Voorhees made an appropriate address.... [25]

Thus, in 1877 Weiss, not Stübinger, was the choirmaster. Then, on August 2 — while “Mr. Julius Weiss, the German teacher, is out of town rusticating” till August 14 — Till Eulenspiegel reappears in a most unexpected form. The ominous heading reads “Behind Prison Bars:”

Simon Rudolph Stuebinger, the notorious musical fraud, whose reputation as such was made clearly manifest in a little over a year’s sojourn in Port Jervis and vicinity some time since, has at last met the rogue’s just fate.

We learn from the New-Yorker Nachrichten aus Deutschland und der Sweiz [sic] of a recent date that Stuebinger was sentenced in one of the courts in the city of Vienna, Austria, during the early part of last month, to three years’ incarceration in a German prison for numerous swindling and other operations perpetrated since he left this country nearly two years ago.

The account states that Stuebinger was the son of a schoolmaster in Beitlau [sic — no such name appears on maps], near Kulmbach, in Bavaria, and that at the age of seventeen he became a school-teacher in Fishback [sic] and other towns in Germany.

In 1867 he married into a family in good circumstances, receiving with his wife the sum of $900. He squandered this money, grew tired of his wife, and deserting her served for a time in the Franco-Prussian war as a hospital steward.

At Orleans Stuebinger distinguished himself in the role of a soldier, for which he received the medal of the Iron Cross. At the close of the bloody war he returned to Bavaria, and finding little or nothing to employ himself at, entered upon a bad course of life. He was arrested for being concerned in a swindling operation and was sentenced to eighteen months’ imprisonment therefor. He served a few months of the sentence, and was released on condition that he would depart the country on the promise never to return to his native land.

In the spring of 1874, or thereabouts, Simon Rudolph Stuebinger arrived in this country, landing in New York harbor, and came directly to this village, where his brother William then resided. He was a person of gentlemanly address and manners, and by profession a teacher of both vocal and instrumental music. To a few of his patrons he stated that he was a bachelor and came direct from Germany to Port Jervis; to others he made known as a fact that he had a wife and four children living in Bavaria, whom he expected to join him as soon as he became established here; and still to others that his wife was living in New York city, whom he visited occasionally as his business engagements would permit. These different statements aroused the suspicions of not a few of his patrons, and when called upon for an explanation he was unable to give even a plausible excuse for his inaccuracies, and endeavored to lead them into the belief that he had been misunderstood, owing to his imperfect knowledge of our language.

During his stay in our midst Prof. S. R. Stuebinger (as he styled himself) claimed to have received the agency for the sale of several makes of first-class pianos and organs in the nearest cities, and succeeded in disposing of a number of instruments in this village and vicinity from the manufactories of Chickering & Son and Knabe & Co. of New York, and Guild, Church & Co. of Boston. He also made purchases of Demorest & Burr of Newburgh, and in nearly every instance swindled the piano men.

Several cases of litigation growing out of the complications have been concluded but a short time, the United States Express Company having been concerned in two or more of the suits brought about by the rascality of this same Stuebinger. These facts are well known to nearly every reader of THE GAZETTE as having been published shortly after the disappearance of this musical genius and prince of rascals from our midst.

As is generally supposed, “Prof.” Stuebinger fled to Europe, and after a two years’ absence from his native country he turned up at Leipsic [sic] in the role of an American physician and surgeon, having in his possession a diploma from a medical college in Lexington to that effect. On the strength of his document he obtained the position of regimental surgeon in the Servian [sic] army. In Leipsic he followed a course of systematic swindling, beating his tailor out of over two hundred marks (some $50), a book concern of a smaller sum, and a dealer in surgical instruments of over $35.

He then went to Eisleben, a city in Saxony, and while there became acquainted with a family named Richter, with whom, on the strength of his plausible stories, he soon became ingratiated in their good favor. He represented himself as the son of a wealthy American farmer, and making love to the only daughter, married her after a short courtship. The elder Richter was in a very short time defrauded by his hopeful son-in-law of some $350, which, it is alleged, he wasted in extravagation and dissipation, when he summarily abandoned his wife and left for parts unknown. Before leaving Eisleben, however, he swindled a merchant out of $50 for camp furniture, a druggist of some $90, besides numerous other sums of a smaller nature.

Stuebinger returned to Leipsic, where he remained but a short time, and afterwards went to Vienna. He put on military airs there and sojourned at the best hotel in the city. He attired himself in the brilliant uniform of a staff officer in the Servian army under some high toned alias, und was feted and courted by the frequenters of the hotel and the nobility of the locality. But unfortunately he relapsed into the old habits of swindling, cheating and defrauding almost everybody with a shrewdness worthy of a better cause. He was at last arrested and lodged in prison.

Before the court Stuebinger claimed that he was an American citizen, a man of honor and a physician of good standing and [illegible], and produced a diploma issued out of Lexington college (Kentucky?), stating that for it he had paid the sum of $80 in America, and on its strength had served as a surgeon in the Servian army, being promoted to Chief Surgeon in the Department for skill in his profession.

Upon a careful inspection of the diploma by experts it was pronounced a forgery, and it is said that the culprit was forced to admit that he had prepared the document with his own hands. By a series of sharp questionings much of Stuebinger’s past life was laid bare to the court.

In the course of the trial the Judge asked him how he dared to sue for the hand of the Richter girl in Eisleben, when he was already a married man? Stuebinger vaguely replied that he was a Protestant.

“Protestant or no Protestant,” remarked the man of law, “you had no right to desert your first wife and marry another without obtaining a divorce, provided you had good and substantial grounds for so doing.”

Stuebinger replied that he had “already obtained a divorce from that woman in America for the sum of $80.” “Do you get everything in America — diplomas, divorces and all — for $80 and the asking?” propounded the Judge, with a wise shake of the head.

Stuebinger was thereupon sentenced for the term of three years to hard labor for his many acts of villainy, with the stern mandate that he should leave the country upon the expiration of his term of imprisonment, under the severe punishment which the law would inflict in case the order were violated. [26]

Notice the recurring pattern. Each time, Stübinger introduced himself in a new environment as a gentleman, whose good manners, refined culture, and social status (music professor, surgeon, officer) won his victims’ confidence, and then hit. But what has all this to do with our story?

On September 13, the Evening Gazette coldly reports: “Mr. Sauer of New York takes the place of Julius Weiss as teacher of the German school in this village.” [27] September 1877 exactly fits the preferred time window Albrecht indicated [28] for Weiss to start teaching in Texarkana. It is a good month to begin classes, and makes for a smooth relocation from Port Jervis — a long, but not impossible train ride. Also, this wipes out that elusive sojourn in St. Louis, Missouri, Albrecht hypothesized but could not document. There, archival digging only came up with another Julius Weiss, a dealer in ladies’ underwear.

Now, to support such theory, we should assume that Weiss left not just the German school, but Port Jervis. Did he? On December 1, the following advertisement appears in the Evening Gazette:

INSTRUCTION IN MUSIC AND

LANGUAGES!

MUSIC FOR BALLS, PARTIES, ETC.,

AT SHORT NOTICE.

PROF. FREDERICK SAUER,

the German teacher, informs the citizens of Port Jervis and vicinity that he is fully prepared to receive pupils for instruction on the Piano, Organ, Singing and the German language.

PIANOS and ORGANS at the LOWEST PRICES.

As leader of the Mannerchor Orchestra he will furnish music for

BALLS, PARTIES, WEDDINGS, ETC.,

at reasonable prices. For information call at residence in First National Bank building, corner Ball and Sussex streets, Port Jervis. [29]

Professor Sauer was replacing Weiss in all roles. Clearly, the latter had left. But then, it is hard to explain why on September 11, two days before that first announcement, the Evening Gazette had:

The building on Front street lately occupied by the Conner Brothers as a market is being repaired. It is soon to be occupied by Julius Weiss as a grocery store and market. [30]

This is utter nonsense. Here, two scenarios are possible. One is, another slip of the journalist’s pen, this time writing “Julius” but meaning “Frank Weiss.” Otherwise, the story is suspect. How could Julius Weiss be planning to open a store two days before he left?

Joplin scholars have long loved this man for his noble, almost parental mentoring of his young pupil beyond racial barriers and prejudice. Little is known of Weiss. No portrait exists and we can imagine him as we like, and would much prefer to see him as a philanthropist. But alas, he was a scammer.

By September 11, 1877, Julius Weiss left Port Jervis — and lots of troubled people behind. This third reincarnation of Till Eulenspiegel is confirmed by a judicial notice, published at least six times, in identical format, in the Evening Gazette of February 12, 19, 21, and 26, and March 5 and 19, 1878:

NOTICE TO CREDITORS. — NOTICE is hereby given, pursuant to an order of the County Judge of Orange county, to all persons having claims against Julius Weiss, of the town of Deerpark, who made an assignment for the benefit of his creditors, to present the same with the vouchers thereof to the undersigned assignee of the goods, chattels, and effects of said Julius Weiss, at the office of Allerton & Mills at Port Jervis, Orange county, New York, on or before the 27th day of March, 1878.

FRANK HADRICH, Assignee. [31]

An identical text follows, concerning a Christian Geisenheimer, probably suspect of being an accomplice. However, he must have been either acquitted or forgiven, for on August 21, 1880, he was among the Männerchor members listed by the Evening Gazette as performing in Honesdale, Pennsylvania. [32]

Thus, Weiss adopted Stübinger’s pattern — he behaved like a gentleman, won people’s trust, swindled them, and left. He displayed much greater sophistication though. Stübinger was a naïve thief, who left much evidence behind, had no prompt answer when interrogated, and ended up jailed at least twice. To date, nothing suggests that Weiss was ever called to respond to his forgeries. People just went to a judge and complained. Justice was largely ineffective in nineteenth-century USA, when the nation was sparsely populated, towns were distant and poorly connected. Anybody could declare anything on any document, and a sense of centralized power was about as strong as in a John Wayne movie. Ironically, the above notice says that Weiss had come to Port Jervis from — or had lived in — the adjacent town of Deerpark, New York, on the aptly named Neversink River.

The story ends with the Evening Gazette of January 19, 1878 issuing a melancholy paragraph as a consolation for the twice seduced-and-abandoned Singverein:

One of the substantial organizations of Port Jervis is the German Mannerchor, which last night celebrated its eleventh anniversary. There is probably no people so sincerely friendly, so good-natured, and so entirely harmonious, as the Germans. Whatever is done seems to be considered right, and no disturbances ever mar the pleasure of their gatherings. The Port Jervis Mannerchor numbers among its members most of our best German residents. We hope it will live to celebrate anniversaries as long as it is useful for societies to exist. [33]

Some readers may still trying to convince themselves that the Till Eulenspiegel of Port Jervis is not the Julius Weiss we have known. But have we ever known him? All info we have comes from the 1880 census, plus belated family memories: no arrival and departure dates. It is generally assumed that, shortly after Rodgers died (1884) and his family sold his three sawmills to survive, Weiss quit as well. Not so. Surprisingly, Weiss spent many years and did many things in Texarkana, as we learn from the New York Herald, September 16, 1889:

MAN AND MONEY MISSING.

TEXARKANA, Ark., Sept. 15, 1889. — J. Weiss, who has for ten years been a resident here as a music teacher, then a school keeper, pawnbroker and jeweller, and lately president of the Texarkana Savings Bank, but more recently a large stockholder in the H. S. Matthews Lumber Company, the largest concern of the sort hereabouts, has decamped, going no one knows where, carrying with him, it is alleged, funds of other parties estimated all the way from $30,000 to $50,000. [34]

For those who might suggest that “J. Weiss,” a music teacher, could instead be named John, Jack, or Joe, the Fort Worth Gazette of September 14, 1889 removes all doubt.

Special to the Gazette.

TEXARKANA, TEX., Sept. 13. — Mrs. Caroline Marx, by her attorneys, sued out an attachment yesterday against Julius Weiss of this city in the district court on a debt of $2000 borrowed money. Mr. Weiss is a prominent capitalist of this city and was lately the president and manager of the Savings Bank of Texarkana. The plaintiff and her attorneys are in a position to know Mr. Weiss’s business, and as they allege in their petition and affidavit “that the defendant secretes himself so that the ordinary process of the law cannot be served upon him,” the rumor is in circulation that he has left the country. His liabilities, if any, are unknown. Other attachments have been run to-day, and the street are full of wild rumors concerning the movements of Weiss and the amount of his liabilities. A short while since he bought an interest in the Matthews lumber company, one of the largest mill plants in this section, and became one of its officers. His non-appearance has alarmed the creditors of that company, and a number of attachments have been sued out to-day. Among them are L. C. Demorse of this city, $277; William Beehan, $8704; R. H. Eyler, $1566; C. E. Whitner, $300. It is supposed that a large number of attachments will be added, as it is understood Leon and H. Blum of Galveston and other foreign creditors have large interests in the mill. [35]

Till Eulenspiegel’s fourth reincarnation was a much bigger coup than the third one. This had been shyly hinted at on a local bulletin, selling perhaps in the low hundreds. The new one was bouncing up and down the nation. As far north as Pennsylvania, the Bradford Era of September 16 has:

TEXARKANA, Ark., Sept. 15. — Prof. J. Weiss, one of the oldest and wealthiest citizens of Texarkana, late president and manager of the Texarkana Savings Bank, is missing with $37,000 of other people’s money. He was a man of examplary habits and his escapade causes the greatest surprise. [36]

The final remark would have probably fit a widespread feeling in Port Jervis, eleven years earlier. The New York Times, Pittsburg Dispatch, St. Paul Daily Globe, and Omaha Daily Bee of September 16, as well as the Indiana Progress of September 25, have the same news as the Herald, plus the following comment:

Mr. Weiss was not looked upon as a man of means himself, but being of fine address and an excellent accountant, and of exceptionally good habits, he was readily trusted by those with whom he came in contact. His marriage in the wealthy and influential Blum family at Galveston several months ago served greatly to strenghten public confidence in him, and the announcement that he had proved a defaulter falls, consequently, with greater weight. [37]

Musicologists will surely agree.

As for Weiss being married, no proof has emerged. The Galveston Daily News, on August 23, soberly informed: “J. Weiss of Texarkana is in the city.” [38] He had been signaled there on March 26, 1888 as well — and that is all. [39] My doubts on such marriage will be made clear in a moment.

The Fort Worth Daily Gazette, always ahead of competitors, has more on September 17:

Special to the Gazette.

TEXARKANA, TEX., Sept. 16. — Liabilities continue to develop against Julius Weiss, the alleged absconding banker. On the Arkansas side, a receiver was appointed who was saved the responsibility of his position as there was nothing to receive.

On the petition of L. & H. Blum of Galveston, the affairs of the Matthews lumber company were placed in the hands of a receiver today. Judge Shepperd, who is now holding district court at Linden, appointed W. L. Whitaker of this city as receiver and the appointee took possession this evening. Creditors continue to pour in but there is hope that the company will pay a handsome dividend. [40]

Later in the same issue we read:

Suits instituted today in the district court were: Mary Hardin vs. the Catholic Knights of America, for $2000; Texarkana National Bank vs. J. Weiss, $1100; J. C. Whitner vs. J. Weiss, $1265. [41]

The Omaha Daily Bee of September 21 takes it more lightheartedly:

It is a long weary way from Arkansas to Canada at this season of the year, but J. Weiss, of Texarkana, is supposed to have recently made the trip. He had the foresight to prepare himself for the cold of the northern winter, and lined his pockets with fifty thousand dollars of other people’s money. [42]

Such a not-so-underground railroad to Canada must have been common guess — and a common choice. But did Weiss really go up North? As people grow old, they show a marked tendency to relocate toward sunnier climates. Albrecht had gleaned fragmentary but convincing data suggesting that Weiss spent five years in Houston, between 1895 and ca. 1900. Then, obscurity. [43] We can now expand this period to a decade.

Again, one must be wary about false or feeble tracks. The Omaha Sunday Bee of February 16, 1890 has a “Julius Weiss” from Austin speaking at a Sängerbund festival — [44] a mouthwatering occurrence which, alas, is a slip of the pen, for the chronicler meant Julius Schütze, editor of the noted German-Texan newspaper, Vorwärts. The Fort Worth Gazette of May 9, 1890 has a “J. Weiss” from Texas lodging at a city hotel — a bit vague. [45] But Morrison and Fourmy’s Directory of the City of Houston, 1890–91, presumably compiled by late 1889, has a “Weiss Julius, agent, pawnbroker, jewelry, watches, 78 Travis bt Preston, Prairie, bds Mrs. H. M. Dusenberry.” [46] This is our man for sure, his activities matching those he had had in Texarkana. The 1892–93 edition has “Weiss Julius, mgr M. Mercer, 514 Main, bds Mrs. H. M. Dusenbery” (single r here). [47] Hence, the fugitive Weiss soon found a lodging in Houston, where he spent at least the following ten years.

Another interesting, albeit slightly puzzling, piece of evidence comes from the Galveston Daily News, June 24, 1891, which, under the heading “The Ursulines Academy Commencement,” has: “The following attractive commencement programme will be rendered to-morrow evening at 7:30 p.m. at the Ursuline convent;” [48] then, as was common in nineteenth-century U.S. newspapers, titles are listed on the left side of the column, composers or performers on the right. However, the latter rule is inconsistently followed and, as we come across “Sounds from Home......Julius Weiss,” we wonder whether he were composer or performer. Apparently, the journalist took him to be the composer, yet Sounds from Home was a then-known piece by Josef Gung’l. Thus, either he was the soloist, or conducted the bizarre ensemble, with piano, violins, guitars, and a zither, all played by young ladies. Taking part, in whatever role, in this Academy Commencement suggests that he was a music teacher at the school the well-known New Orleans Ursulines had opened in Galveston — perhaps a second job, as music had always been to him.

Weiss’s presence in town sheds a different light on earlier data. Had he really married Miss Blum, of the noted Leon & H. Blum firm, a major victim of the Texarkana scam, the Blums should be furiously chasing him, and he would not step into the lion’s den, let alone with his real name on the city Daily News. As a consequence, either this is another Julius Weiss, or, more likely, he had invented his — so far undocumented — marriage to better swindle Texarkanans, in a genuine Eulenspiegel vein.

This said, Weiss’s life in South Texas is largely a mystery. There are perhaps a dozen articles in the Galveston Daily News citing the musical activities of a “Prof. Weiss,” matching those he had held in Port Jervis, but never adding his given name; and it is clear, from other clippings, that there were two or three people who could be called “Prof. Weiss” who played music. He is still a tenant here and there — not the lifestyle we would expect of a man who has just cashed $50,000. Was he forced to return the money? But this would imply a trial and serving a prison term, two events at variance with the consistent evidence of him being a free man. On the other hand, after the huge exposure of his scam in the national press, he would certainly not go to a bank, say “My name is Julius Weiss,” and deposit $50,000. Was he swindled in turn? Did he squander the money? Did he give it to the poor? Most importantly, what are the date and whereabouts of his death?

All we know is Lottie Joplin Thomas’s oft-cited statement, attesting that Joplin sent him money on occasion, until he died. [49] This would place Weiss’s death between 1907 and 1916, that is, at a reasonable age between 66 and 75. I could only find one Julius Weiss whose date of death falls in this range. He died in Beaumont, Texas, on February 27, 1913, and is buried in the Hebrew Cemetery. The Houston Jewish Herald-Voice Index to Vitals and Family Events, 1908–2007 calls him “Professor” (and spells his last name “Wiess”). [50] Beaumont is very close to both Galveston and Houston, which adds credibility to the finding. However, there seems to have been another Weiss family in Beaumont; the birth date is given as 1847 (perhaps someone mistook a 1 for a 7?); and the lack of further evidence leaves this document in shaky isolation, unless a connection is found with what the Galveston Daily News reports on May 28, 1905:

WEISS STORE BANKRUPT.

One of Beaumont’s Big Establishments Sued by Creditors.

SPECIAL TO THE NEWS.

Beaumont, Tex., May 27. — An involuntary petition in bankruptcy was filed today against the Martin Weiss Dry Goods Company by three New York creditors with claims aggregating $25,000. Julius Weiss has been appointed receiver and the business will be continued without interruption. Mr. Weiss has been a heavy loser in oil investments in the last two years and it is on this account that the difficulty has arisen, the dry goods store being one of the best paying in the city. It is anticipated that a compromise will be effected with the creditors and all claims settled at an early date. All local creditors are well secured. [51]

Was this “our” Julius Weiss? Was he, once again, involved in a bankruptcy, but this time on the opposite side? Or was the journalist confusing all those Weisses?

If this research answered many questions, perhaps twice as many emerged. We do not know whether Weiss was ever sentenced in Germany, as Stübinger was, to a prison term followed by forced expatriation. Nor we do know what he did in 1870–74 before reaching Port Jervis (another scam?), whether he knew Stübinger there or in earlier times, whether they were already twin souls in the art of swindling, or whether Weiss got the idea for the first time from his friend and refined it. We do not even know whether he, in his final years, contacted Joplin and asked for money, and whether this was his last scam.

However, the biggest question is: who was this man who, on one hand, repeatedly swindled and stole while, on the other hand, gave free music lessons to a Negro child, the son of a maid servant, for perhaps as long as seven years (1877–84)? Was he suffering from multiple personality disorder? Or was he individually pursuing an social justice utopia, conflating Till Eulenspiegel and Robin Hood into the inspired agent of a higher will, be it a deity or the laws of history?

Right now, any conclusion is subject to revision. However, I cannot help but think of Weiss mesmerizing his young student with wondrous tales of the great European music masters, pointing him to the overwhelming emotional power of choral music, playing four-hand piano duets — then a common teaching practice — such as Schubert’s Military Marches op. 51, echoes of which I perceive in A Breeze from Alabama — an intimate Singverein, for want of a larger one.

In Weiss’s complex personality, two levels seem to coexist — the German idealist à la Schelling, taking music as a magic ladder to a lofty world of pure spirit, imprisoned in a greedy, pragmatic English-American society where money is all, culture is a waste of time, and there is no room for one’s mind to wander in search of spiritual nourishment. Perhaps Weiss yielded to the jungle law while hating it, and conceived his scams as a revenge of intelligence, culture, and spirituality over ignorance and narrow-mindedness. Perhaps he was generous with those he deemed worthy, like young Joplin. He was thus remembered by Rodgers family members.

In musical terms, everything is clearer. Weiss was a typical product of the Singverein movement — although, I concede, not of its ethics. First, he was a German musician. Such identity owed next to nothing to Wagner, of whom he could have heard in Europe Der fliegende Holländer, Tannhäuser, and Lohengrin, if he ever did. On the contrary, musicians from his generation and milieu were at home with Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Weber, Mendelssohn, and — among older masters — Händel. There is no evidence that he ever tackled Italian or French music, nor more advanced creators, such as Liszt, Brahms, or Bruckner.

Thus, the Joplin–Weiss encounter, as improbable as it looks, belongs in a general trend. It places Joplin squarely in the school of black composers who faced the daunting task of carving a Negro musical identity out of the German musical style, his company being Will Marion Cook, Harry Lawrence Freeman, and even Samuel Coleridge-Taylor. They form no string of random incidents. Simply, they appeared when the English-speaking world was aping Germany in search of the musical refinement it lacked; after all, Sousa, MacDowell, and Ives were fed on the same diet. Joplin’s genius was just stronger, his goals both loftier and vaster, his path entirely personal.

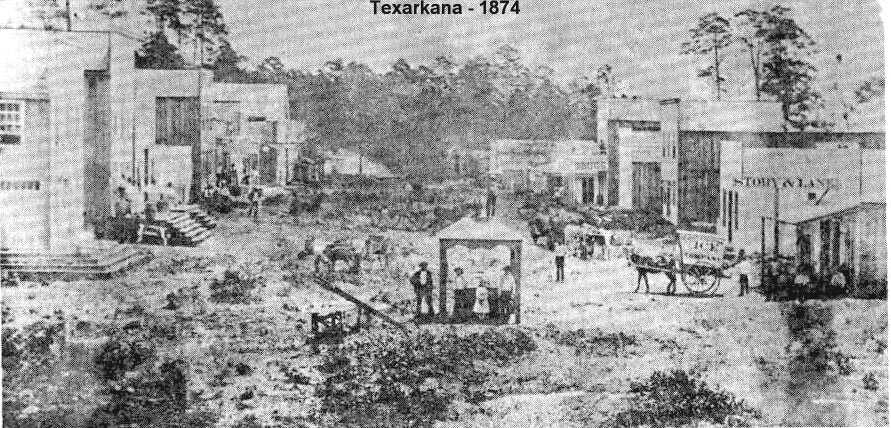

Context IV: The Ghios and the Orrs

Wellge’s map is not our only visual source on early Texarkana. The oldest existing photo dates 1874. There is not much of a city yet; one can see a well at the center and, before it, a five-year-old girl in white robe, with adults, probably her parents, behind her. [52] The girl was Ambolyne Ghio, and her father was Italian. Theirs is a fascinating story.

Figure 3. The oldest photo of Texarkana. 1874.

Antonio Luigi Ghio (pron. GHEE-oh) was born in Genoa in April 1832. Research in city archives is still going on; so far, no original certificate has resurfaced. Ancestry.com gives 1849, which in fact should be his immigration year, as we shall see. Such a date places Ghio in America well before the high tide of Italian immigration triggered by poverty, famine, and soil erosion. Texarkana’s Sacred Heart Cemetery registers many such second-wave Italians, however Ghio belonged in an earlier world. His family boasted an ancient lineage and a coat of arms. According to the same online source:

Anthony came to America, landing at the port of New York. In that city, he found employment as a traveling salesman for a N.Y. firm, travelling principally in the South and the Caribbean Sea. He was in New Orleans and Shreveport, La. early in 1852. Later he went to St. Louis, Mo., where he entered into business and after a short time there he returned to New York and again became a commercial traveller, making that city his headquarters.

Anthony met the woman who would become his bride, Augusta Casassa, in Boston, Mass. She...was also born in the province of Genoa, Italy, but had been reared in Boston. From there, the Ghios went to Illinois, spending time in Cairo, Chicago before they made a much larger move to Jefferson, Tx. In this Texas city, Mr. Ghio was successful at everything he undertook, and it was here [that] he began to amass the fortune that he would eventually share with his devoted family and church. [53]

Another source adds fascinating details:

In the fall of 1873 news leaked out that a town would be constructed where the Texas & Pacific and the Cairo & Fulton railroads met on the state line between Texas and Arkansas. In early December, enterprising men from all over the region rode onto the site and camped out, in order to be there on December 8th when the sale of town lots began. It was important to get there early and claim the choicest lots, if these men would make a profit from their speculative land purchases. Gus Knobel, surveying engineer, and Major H.L. Montrose, special agent of the Texas & Pacific Railroad Company, opened the sale that day by announcing lot prices: $350 for corner lots and $300 for inside lots.... Anthony L. Ghio rode a horse from his home in Jefferson, Texas, to purchase several prominent city lots, both commercial and residential. One of these lots was located at the corner of W. Broad Street and State Street (later renamed Main Street), where Ghio built his famous Opera House. [54]

Back to the earlier source:

In 1874, Mr. Ghio moved his family from Jefferson to Texarkana and he quickly established himself in a completely finished and furnished home at the corner of Third Street and Texas Avenue. It was here that several of their children were born.

Mr. and Mrs. Ghio helped organize and establish the first Catholic church in Texarkana, Tx. and later the first Catholic school. Their home was a frequent rendez-vous for the bishops and visiting priests.

In 1877 Mr. Ghio and Capt. F.M. Henry built the first opera house in Texarkana, which also was the first brick building to be erected in the city. It was located on the corner of Broad Street and Texas Avenue. In 1884 Mr. Ghio built a more elaborate theater, up-to-date and well appointed. [55]

Ghio, who passed away in 1917, gave Texarkana tremendous boost. He ran for mayor of the Texas half of the city (which still has two mayors), won three elections (1881, 1882, 1883), and retired while being still quite popular. [56] He had seven children, one being Ambolyn. She was to marry — no unusual choice in town — a railroad supervisor, John Lewis Griffin. The couple had a daughter, Corinne, who turned up to be, no less, “the Orchid Lady” of the silent screen, Corinne Griffith (1894–1979). Born in Texarkana, she was rated the most beautiful movie star of her age (calling her “actress” would be slightly inaccurate) and, like many, was a casualty of the introduction of sound. After termination of her career and amidst various marriages, Corinne Griffith wrote books on a variety of topics, from cooking recipes to football to taxation (she was against). Her 1952 autobiography, Papa’s Delicate Condition, sketched a picture of her childhood in Texarkana. [57]

The fact that an opera house existed in Texarkana, when Treemonisha’s composer-to-be was a child, is not unknown to scholars, but has been overlooked so far. Edward Berlin cites the 1891 articles reporting how the Texarkana Minstrels, including Joplin, appeared there and got involved in a weird incident. [58] But Ghio’s Opera House opened in 1877, when Joplin was ten and Texarkana three. For some time, it was the only place in town (or county) where entertainment of any sort was being offered. It planted a seed. Theater was to become central to Texarkanans’ life; in later decades, the city came to boast eleven such venues. (Another noted Texarkanan, Ross Perot, funded the renovation of one of them.)

It is hardly surprising that a Genoese born in 1832 would build an opera house in the wilderness, in Fitzcarraldo fashion. The Teatro Carlo Felice, inaugurated in 1828 with Bellini’s Bianca e Fernando, was a veritable center of Genoa’s intellectual and social life. Opera goers were entertained and moved by Romantic subjects, often about conflicts between stiff social rules and free individual impulses, love stories across social barriers, fights for freedom, national and ethnic revolt against an oppressor, political prosecution, and exile. It is hard to imagine the Bowie County residents, with all of their Confederate nostalgia, eagerly awaiting such fare. On the contrary, Ghio must have loved it, at least judging from his personal vicissitudes.

For eight centuries, Genoa had been a republic founded on free commerce and a powerful business net, including slave trade. Africans were liberated in an outburst of popular rebellion in 1797, when the Jacobins staged an elaborated public chain-breaking ceremony. Then, Genoa lost its independence, and the 1815 Vienna Congress assigned it to Piedmont Savoia kings. A popular revolt broke in March 1849, repressed with massive support from English cannons, between April 5 and 11; the insurgents received only limited help from a U.S. brigantine passing by. Repression quickly turned into manslaughter, with killings of unarmed citizens (including children), robberies, rapes, and even prisoners forced to drink urine. [59]

If April 10, 1849 is actually Ghio’s emigration date, as it should be for other dates to make sense, then he escaped the repression on the U.S. brigantine (which would explain the lack of entry reports), safely heading to the country that had supported Genoese freedom. In light of this, could he have endorsed the oppression of minorities? And was the building of a theater in Texarkana just “business as usual”?

Of course, there is a wide gulf between building theaters and staging operas. Apparently, Texarkana had no stable orchestra, although reports from different years inform that it had a Cornet Band, [60] a ladies’ band, [61] and also a string ensemble, [62] engaged for a society ball when the railroad connected Texarkana to Shreveport, Louisiana. Reconstructing activity and seasons, by combing period newspapers, is a task worthy of a separate essay. However, a cursory online search yielded some data, hereby summarized.

As we said, Ghio’s Opera House was built in 1877 and was soon successful. An historian wrote:

During the fall-winter season, Ghio’s Opera House featured the best touring acts available, and seats were sometimes difficult to come by. It was Ghio’s intention to have none but “stars” during the season in Texarkana. Often the performers took to Texarkana streets to draw crowd for their evening performances. [63]

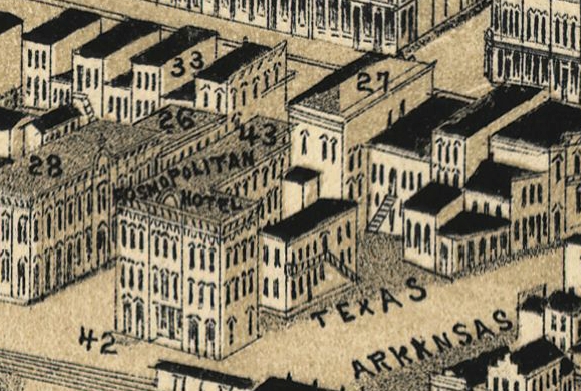

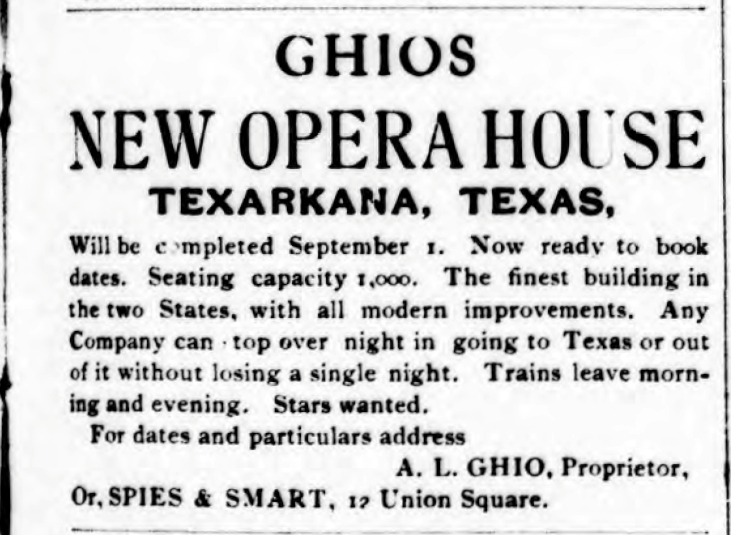

Not surprisingly, a competitor soon appeared, called Orr’s Opera House. Orr is a recurring last name in Texarkana history. A Mr. G. M. Orr visited the area in 1864 and found only four families. [64] Later, in an unspecified year, the Orrs built the first school for black children, usually indicated as the one Joplin attended. Actually this is unproven. There is a photo of the two-story building, [65] then it is known that a fire destroyed the upper floor on February 1898, probably burning all documentation. The ground floor was restored and the resized building is still in place, in the 800 block of Laurel Street. Similarly, there is no evidence as to when Orr’s Opera House appeared, however it hosted what seem to have been lavish productions in 1883–84. This date is perhaps not coincidental, for Ghio’s Opera House burned in 1883, but was soon rebuilt on the same spot. Its rear view is marked by no. 27 on Wellge’s map (fig. 4). Ghio announced its second opening for September 1, 1883, in the New York Dramatic Mirror (fig. 5).

Figure 4. Henry Wellge (1850–1917), Perspective Map of Texarkana.

ca. 1888. Detail of Ghio’s Opera House. [fn66]

Figure 5. Ghio’s Opera House advertisement. New York Dramatic

Mirror, September 1, 1883. [67]

The theater manager position underwent frequent replacements, with Ghio himself serving in such role on occasion — evidence of his deep involvement in the matter.

No further information has been found on Orr’s Opera House. Period newspapers vaguely report another fire by January 1895, but specify neither its date, nor which building it affected. Perhaps Orr’s, because Ghio’s burned again on May 25, 1898. [68]

Amidst all these conflagrations, the San Francisco Call, October 10, 1897, issued actress May Vokes’s impressions.

Figure 6. “May Vokes Tells of Touring in Texas” article. [69]

She does not say which venue hosted her performance, however her overall picture is hardly as glamorous as Ghio’s advertisement suggested, leaving the doubt it was not the same building. Also, much of her despising attitude may be traced to the traditional arrogance of the diva for whom no place is up to her status, and anything below Buckingham Palace is a “barn.” [70]

Down there [in Texas] everything which is used for theatrical purposes is called an “opera house,” whether it be a barn or a church fallen from grace. The “opera house” at Texarkana was as near a barn as you can imagine, and a decidedly battered barn at that. The little box-like rooms which had been intended for dressing rooms were so small that we had to leave our trunks outside, and so low down that it was only by the most careful arrangement of posters that we could secure any privacy at all. [71]

From news in the period press, we learn that Ghio’s was used for political gatherings, benevolent fundraising, lumbermen’s conventions, lectures, minstrel shows (about once per month), concerts, musical theater, and drama. It hosted some (then) celebrated stars of the musical comedy such as Patti Rosa, Myra Goodwin, Roland Reed (more than once), Adelaide Moore (from England), the Gilbert–Huntley Comedy Company, Stuart Robson, and Frank Jones. Top-notch drama companies and stars also performed; Lewis Morrison’s then-celebrated rendition of Mephistopheles in Faust met with great success at Ghio’s, as did Alexander Salvini (few months before he died in Florence), Marie Wainwright, Newton Beers, Stuart Robson, and the masterful Victorian melodrama, The Silver King, by Henry A. Jones and Henry Herman, which Texarkanans could applaud a mere three years after its English première at Princess Theatre, London. In the realm of concert music, it is worthy of notice — although by then Joplin was in Sedalia — that the Blind Boone Concert Company ”drew a full house” on March 1, 1897. [72]

So far, no solid evidence has emerged of a full opera being staged at Ghio’s. What comes closest is the Kimball Opera Comique Company, a sixty-piece organization with singers, a well-trained choir, dancers and players, which won widespread popularity with its fusion of opera, operetta, and burlesque, as exemplified by such titles as Carmen up to Date (which toured Texas in 1892) and Hendrik Hudson, Jr., or the Discovery of Columbus, staged in Texarkana to great success on December 26, 1895. [73] The dressing rooms had to be quite large to accommodate such troupes.

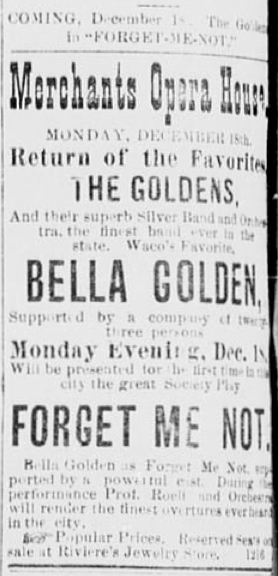

As for Orr’s, it enjoyed at least one brilliant moment. A clipping from the New York Dramatic Mirror reports that, under Thomas Orr’s management:

Bella Golden came April 30, to good business. The play, Forget-Me-Not, was poorly done. The band and orchestra, under the leadership of Professor Rodi, were splendid. [74]

Figure 7. Forget-Me-Not advertisement. [75]

Bella Golden was a first-rank actress, and Forget-Me-Not was a warhorse of hers. As for Professor J. M. Rodi, he was a noted band and orchestra conductor. Reference to “band and orchestra” leaves no doubt that many instrumentalists were employed. This is confirmed by an advertisement in the Waco Daily Examiner, December 17, 1882, seemingly for another date from the same tour (see image to the right):

The “company of twenty-three persons” looks like a separate body of artists from the “superb Silver Band and Orchestra,” which “will render the finest overtures ever heard in the city.” A bit more cryptic yet unequivocal is a clipping from the New York Dramatic Mirror of April 14, 1883:

Orr’s Opera House (Thomas Orr, manager): Kiralfys’ Black Crook, March 22, to good business. Haverly’s Merry War, 2d, to fair house. [76]

The Jewish Hungarian dancers, Imre and Bolossy Kiralfy (originally Königsbaum) were renowned for their lavish productions, with “large female chorus lines, high-quality sets and costumes that were usually made in Europe, and innovative special effects.” [77] Their remake of the 1866 classic show, The Black Crook, was up to their fame, judging from surviving images. “Haverly” means Haverly’s English Opera Company, property of John H. “Jack” Haverly, a promoter who had worked with minstrel troupes and then switched to operetta, producing only one show per year with good singers and a complete orchestra. For his long 1883 tour, which reached Texarkana on April 2, he chose The Merry War, that is, Johann Strauss, Jr.’s Der lustige Krieg, comic operetta in three acts, premièred in Vienna, Theater an der Wien, on September 25, 1881. Texarkana’s theatrical life was on the cutting edge of events — the ink had barely dried on the score.

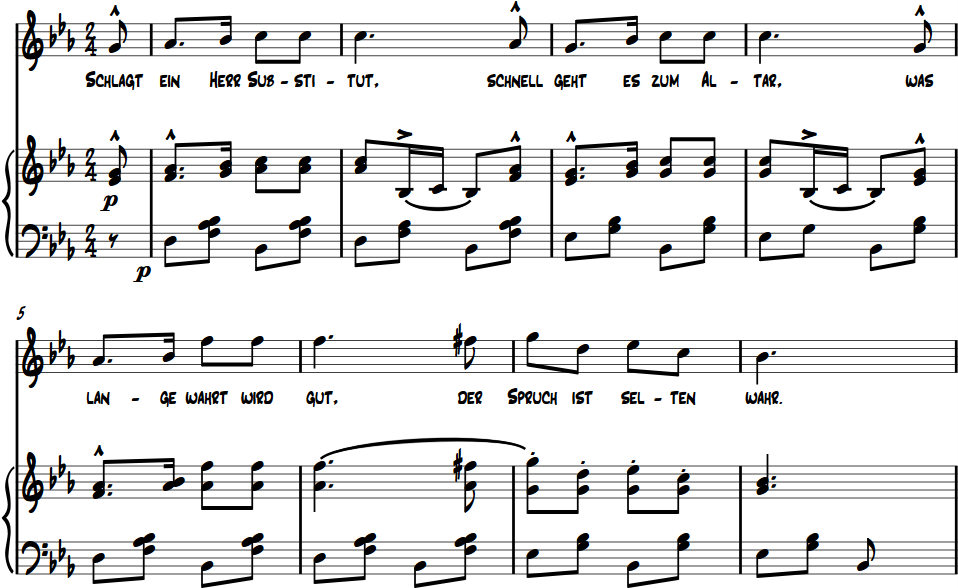

This is the first more-or-less opera we know to have been performed in town as such. Strauss’s name comes to us as an enlightening discovery; that Joplin was familiar with his music is apparent from his early, unsyncopated waltzes, one of which, The Augustan Club, also contains an unequivocal yodel pattern in the right-hand countermelody of the A strain. One also finds other specific links. Consider, for instance, the finale of Act I, “Was lange währt, wird gut,” sung by Violetta and choir.

Example 8. Johann Strauss, Jr. Der lustige Krieg, Act I, Finale (“Was lange währt wird gut”).

Compare the passage above on the words: “Schlagt ein, Herr Substitut, / schnell geht es zum Altar:” with the D strain of Combination March, in the same key of E-flat major:

Example 9. Scott Joplin, Combination March, D strain.

Alas, such similarity, while striking the ear as egregious, relies on commonplace patterns, and is hardly conclusive in itself. Yet it leaves the impression that Strauss’s snippet had sunken, as it were, into Joplin’s subconscious, to resurface years after. As we learn more about Texarkana theatrical seasons, further connections may emerge.

Audiences must have been heterogeneous. Wealthy people are reported to have attended (a man was robbed of a $300 diamond shirt stud that he was wearing); [78] minstrel shows might have catered to more popular patrons. May Vokes describes her audience as rather impolite. No info has surfaced so far as to whether segregation was in use.

But this bears little relevance here. Joplin was performing in a minstrel troupe in 1891, staged The Ragtime Dance in 1899, was busy with A Guest of Honor in 1902–03, with Treemonisha from 1906 on; and was composing If in 1916. Taken together, these involvements with theater stretch over a quarter of a century — half of his life. As we learn that he might attend Ghio’s, some six blocks from home along State Line Avenue, as early as 1877, the total raises to four fifths of his life. Theater was no one-time tourist excursion to him. This looks even truer when considering, as I suggested elsewhere, [79] that some of his piano pieces are actually theater on the keyboard. Joplin’s old image as a “rag pianist” stems from his rediscovery in a moldy-fig perspective that was foreign to him. He must have seen himself as a stage composer.

Now, in order to write for the theater, one must go to the theater. There is no other way to learn the craft. Treemonisha has been described as dramatically weak; yet, not one of Joplin’s abundant and careful stage directions is ineffective, impossible, clumsy, impractical, or betraying a lack of experience and showmanship. Every detail is calculated. The banjo arpeggio opening “We Will Rest a While” is no frill — it is there to give a cappella singers the pitch. There is an effective dance number per act, each one different, each choreographed by Joplin himself. And each act has a real finale.

Also, from what is known about A Guest of Honor, Joplin respected Aristotle’s three unities (time, place, action) in all of his stage works. He was conversant with the grammar and syntax of the medium, and could even add genial twists to tried-and-true stage solutions. There is no dearth of ballet scenes in opera, yet who had ever conceived a bear dance? As far as I know, only Pier Francesco Cavalli in La Calisto, a seventeenth-century work, drenched in Baroque taste for the marvelous and the magic — a score Joplin could not have known. And who else wrote a three-act opera in which the main character is gagged during most of Act II? Both elements are redolent of Mozart’s Zauberflöte, however only as a generic starting point from which Joplin substantially departed. His wild animals are not tamed by humans; they are tame, and humans shout them away. Papageno’s padlock is humorous, Treemonisha’s gag is not, as we shall see.

In such a small town, it is safe to assume that, sooner or later, everybody went to the theater, if only for a benevolent meeting. As a black teenager, Joplin could easily be assiduous; a valet job, for instance, would earn him salary plus tips. And he could have watched anything from minstrelsy to Strauss, while daydreaming of his future — a natural extension of what Antonio Ghio had dreamed for him and for all Texarkana youth.

Years of Train(ing)

As far as we can say at this early stage, Ghio’s policy was far from Germanophile. It was rather Anglophile, possibly due to the audience’s predominant ethnicity. Drama and musical comedy abounded; English stars were welcome. There was little room for pure, abstract music.

Thus, young Joplin must have been caught between two contrasting sources of information and inspiration — the masterpieces Weiss told him of, and the actual theater in town. Could he also experience the former firsthand? The answer is: yes. We do not know whether he did, of course, however the possibility logically stems from the combination of two above-described elements: Texas Germans and trains.