Artie Shaw in New Zealand

Aleisha Ward

Introduction

Clarinetist and bandleader Artie Shaw was at the peak of his popularity when he enlisted in the United States Navy in early 1942. [1] In spite of this, very little has been written about Shaw and the band he led in the Pacific theater of war in 1943. While this period may not have been full of important musical innovations, to the audiences that the band entertained their presence was very important. For troops and civilians alike, this was a small but important event that took them out of the day-to-day reality of war. This article aims to illuminate a small portion of Artie Shaw’s Pacific tour, chronicling the month he spent entertaining military personnel and civilians in New Zealand, and revealing aspects of the impact that the Shaw band had on the local jazz scene.

Background

When the United States of America entered World War II in December 1941, the necessity for bases for training, rest, rehabilitation and evacuation around the incipient Pacific war theater became urgent. In early 1942, New Zealand was designated a training and rehabilitation base for U.S. troops in the Pacific war theater. [2] Between June 1942 and October 1944, several hundred thousand American men and women passed through or resided in New Zealand, increasing the population base by ten percent. [3] The interaction with Americans affected New Zealand society and culture, and had a significant impact on New Zealand jazz through the swing bands with the American troops.

By the time that American troops arrived in New Zealand in 1942, New Zealand had been involved in the war for nearly three years. The American troops and support personnel arrived in a country that was in the grips of blackout precautions (from the threat of Japanese invasion) and with severe rationing of all consumer items, with as much material as possible going to support the British civilian population and the general allied war effort. [4] The rationing and blackout conditions affected businesses as much as individuals with cinemas, cabarets and other entertainment venues only opening for limited hours. [5] Added to this situation was the fact that New Zealand was without much of a generation of young men, as the majority of men between 18 and 40 were serving in the armed forces, primarily overseas. [6] This was a shock for young men and women who had (until that point) only been lightly touched by the war.

Although the American personnel were in New Zealand for the purposes of war, there was still time for relaxation and having fun particularly at dances and cabarets with the locals. Much of the entertainment for the American troops was locally organized and produced, but there were also tours organized by various branches of the armed forces, and by the United Service Organization. [7] The most significant of these tours was by Artie Shaw and United States Navy Band 501 in 1943.

The Artie Shaw Tour [8]

| Artie Shaw Navy Band New Zealand Tour 1943 | |

| Trumpets | Frank Beach, Conrad Gozzo, John Best, Max Kaminsky |

| Trombones | Earl Le Favre, Tasso Harris, Vahey ‘Tak’ Takorian |

| Saxophones | Mack Pierce, Ralph La Polla (alto); Sam Donohue, Joe Aglora (tenor); Charles Wade (baritone) |

| Piano | Roscoe ‘Rocky’ Coluccio |

| Accordion | Harold Wax |

| Guitar | Al Horesh |

| Bass | Barney Spieler |

| Drums | Dave Tough |

| Arrangers | David Rose, Dick Jones |

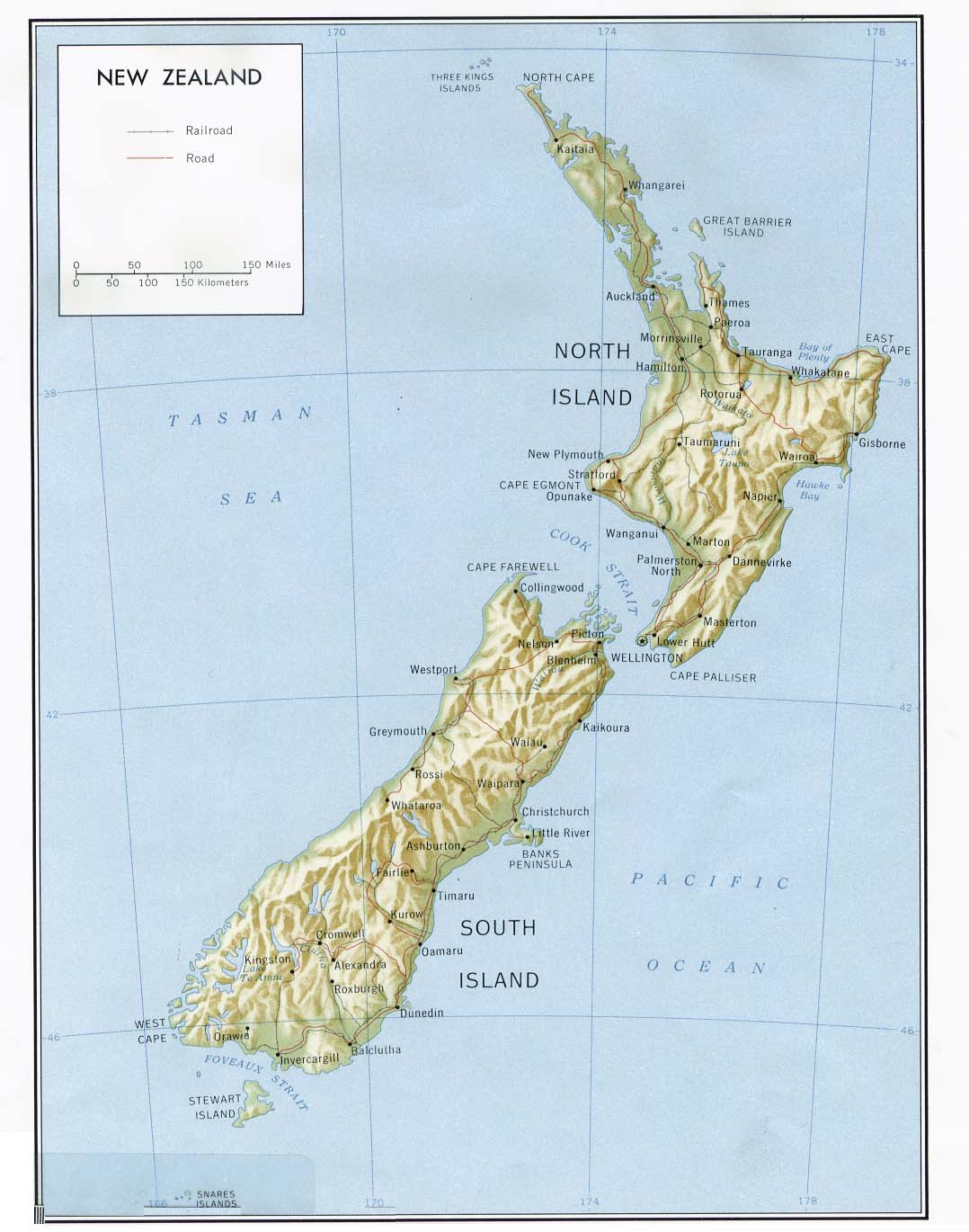

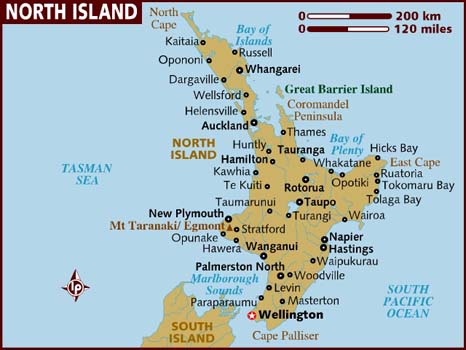

By the middle of 1943, the number of United States forces stationed in New Zealand was at its peak, with approximately 50,000 personnel spread across the Auckland and Wellington regions. [9] During this time Artie Shaw and the Neptuners (also known as the Rangers) toured New Zealand, entertaining American and returned New Zealand troops.

The band arrived in Auckland on July 30, 1943 after performing for the troops in Nouméa, New Caledonia. Contrary to other activities that peripherally involved the U.S. military in New Zealand, the New Zealand press was apparently allowed to expand on details about personnel and where the band had come from in the Pacific. The press was also allowed to advertise, preview, and review the bands performances, including giving details of distinguished military guests. [10]

The first concert by the Shaw band for a combined New Zealand and American service audience was scheduled for August 1 at the St. James Theater in Auckland city. Given that instruments needed repair following the climate extremes of the Pacific Islands and damage to them following bomb raids when the band was performing for troops at Guadalcanal, the press (both local and foreign) found the fact that they would perform within forty-eight hours of their arrival surprising. [11]

At that first performance, local vocalist Esme Stephens, who was well known for her appearances on radio station 1ZB and with several cabaret bands, was invited to perform two songs with the band: “White Christmas” and “This Love of Mine.” At some point during the day, Noel Peach, founder of Astor Recording Studios, was recruited (possibly by Jack Chignall, Shaw’s New Zealand liaison and a member of the 1ZB staff) to record Stephens’s performance that evening. Peach recorded Stephens singing “White Christmas” on a portable recorder and relayed it via phone line to the Spackman and Howarth recording studio where engineers Dale Alderton and Eldred Stebbing cut it onto a lacquer disc. [12] Unfortunately for local jazz fans, although Stephens sang with the Shaw band, it was without Shaw himself, as he used her set to take a break. [13]

For the first two weeks of the tour, the Shaw band was based in Auckland, performing at military camps and hospital and rehabilitation facilities around the region during the day. The musicians also took time to visit with patients in the facilities, a duty that was occasionally emotionally overwhelming for the musicians. [14] In the evenings, the band performed at concerts and dances at various civilian venues including the Auckland Town Hall, Civic Wintergarden, and Westhaven Cabaret. Importantly, these evening concerts and dances involved both American and New Zealand service people and their civilian guests, which included a number of local musicians. [15]

On August 12, the band proceeded to Wellington, where their performance schedule was similar to that in Auckland: camps and hospitals during the day and concerts and dances in the city at night. During the course of their stay in Wellington, the Shaw band broadcast several times on various Wellington stations. The band broadcast live on August 15 from the Centennial Exhibition Hall studios in Rongotai [ɾɔŋɔʈɪ] (a suburb of Wellington) in between engagements at the Majestic Cabaret. [16] The evening dance on this day boasted the highest attendance of all of the band’s engagements with approximately 2,400 people attending (several hundred people over the capacity of the Majestic). [17]

The Shaw band also played at a welcome home ball for the recently returned New Zealand troops on August 21 held at the Centennial Exhibition Hall in Rongotai. This was the only engagement by the band that was specifically intended for New Zealand armed forces personnel, although there were also American servicemen and women in attendance. The ball was also broadcast live over station 2YA. [18]

The band returned to Auckland on August 25 for several engagements in Auckland and the northern camps, including a dance in the northern town of Whangarei [faŋaˈɾɛi]. At the dance in Whangarei, the Shaw band shared the bandstand with a local dance band led by Cecil Wright, alternating two-hour sets. This was the only time during the tour that Shaw shared the stage with a local band, but unfortunately, no information from the Cecil Wright band about that night has surfaced. [19]

The last engagement of the tour was perhaps also the most prominent, a dance at the Auckland Town Hall on September 1, 1943. This dance was organized by the American Red Cross in honor of United States First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who was touring the South Pacific encampments. [20] Attended by 1,500 servicemen and women, the dance was broadcast live on station 1ZM and was recorded via phone relay by Eldred Stebbing for the American Expeditionary Broadcasting Service network. [21]

Repertoire and Recordings

The repertoire for the tour was mostly unremarked upon by journalists (even music journalists) during the tour. This is not surprising for New Zealand journalists, as even before the war it was rare in reviews of performances for journalists to mention the repertoire of a band. After the war began, noting repertoire in New Zealand review columns became considerably more rare. The introduction of wartime censorship made it a crime to broadcast songs that had “informative” titles (or to print such titles in the press). [22] The only newspaper that appears to have mentioned any repertoire performed by the Shaw band during the tour was the New Zealand Observer, which mentioned in its review of the first concert that:

Their programme was a varied one, including such old favourites as “Begin the Beguine,” “Stardust” and “St. Louis Blues,” and new hits such as “White Christmas,” “This Love of Mine,” “You’d Be So Nice to Come Home To” and “Dearly Beloved.” [23]

This appears to indicate that the repertoire chosen for the tour was broad — as the New Zealand Observer reviewer states including “old favourites” and “new hits” — and designed to appeal to a wide audience that were not necessarily jazz fans. Whether the set list remained the same throughout the tour is also unknown, but it would appear that the repertoire was chosen with an eye to recognizability; songs that the audiences would know, even if only vaguely.

Although this article mentions broadcasts and recordings, as far as I have been able to discover, only one recording remains extant of any of the performances. A copy of the recording of Esme Stephens with the Shaw band made by Noel Peach, Eldred Stebbing, and Dale Alderton is held at the Alexander Turnbull Library in Wellington, New Zealand, as a part of the Dennis Huggard Jazz Archive. [24]

The radio transcriptions that were made by Eldred Stebbing were pressed on glass masters, one to be used by the American Expeditionary Broadcasting Service (the so-called “Mosquito Network”) in the Pacific, and another copy was placed in the New Zealand Broadcasting Service archive. The fate of that glass disc travelling around the Pacific encampments during wartime can be easily guessed. The fate of the disc that remained in New Zealand, however, was remarkably similar. According to broadcaster Bruce Talbot, who worked for the New Zealand Broadcasting Service during the 1950s, a colleague at 3ZB (the Christchurch commercial station where the archives were held) needed the sound of breaking glass for a live program and “it was decided that an old glass transcription disc gave exactly the right effect. After the event my friend was horrified to see ‘Artie Shaw Navy Band broadcast’ on what remained of the label.” [25] According to Talbot, his colleague tried to discover if there were any other copies of this disc still in existence, but without any luck.

New Zealand Reactions

For the New Zealand jazz community the tour by the Artie Shaw band was considered an historic event. Here was a world-renowned jazz musician, with a band that combined musicians from his and other well-known and well-respected jazz bands, and they were going to perform in New Zealand! For a country that only saw the top jazz musicians on film, this was momentous. The mood among the jazz community was apparently verging on ecstatic for anyone near Auckland or Wellington. [26]

Given that many of the band’s engagements were held at civilian central city venues, there were many legitimate and less legitimate means by which local musicians and fans might hear the Shaw band. The most common practice of listening in was to find open windows or doors to listen through. Also popular was attempting to sneak in and hide inside the venue, although this could be difficult with the presence of “officious” caretakers or guards. [27] Saxophonist and pianist Don Richardson managed to gain entrance through a different method: he met an American soldier while attempting to figure out a way either to obtain a ticket or to sneak into the theater, when the soldier could not find a young woman to accompany him he told Richardson that he could be his “date” for the evening. [28]

Some devoted fans serving in the armed forces and unable to get leave even went so far as going Absent Without Leave (AWOL) from their bases. This was a great risk as there were severe punishments if they were caught. However, a number of fans and musicians were apparently willing to risk punishment in order to hear their idols perform.

For musicians, there were two other tactics to hear the Shaw band. Firstly, and most legitimately, the Auckland Musicians Union had made arrangements with the U.S. Naval Headquarters that local musicians were to be allowed admission to two of the service dances at the Auckland Town Hall on production of their union membership cards. [29] The second method was to befriend members of the band. Saxophonist Derek Heine and trumpeter Lew Campbell both managed to strike up friendships with members of the Shaw band and were allowed to sit in on a few numbers. [30] Tenor saxophonist and Canadian expatriate, Art Rosoman, renewed his acquaintance with saxophonist Sam Donahue, with whom he had played some years previously. [31] Other musicians met members of the Shaw band when the band came to cabarets and clubs after the end of their engagements, or at parties and jam sessions to which Shaw band members had been invited. [32]

No matter how local fans and musicians were able to hear and see the Shaw band, the impressions were the same: astonishment and awe. Musicians and fans report that while they had thought that the bands with the American troops were the best that they had ever heard perform, that quickly changed when the heard the Shaw band. Using terms such as “unbelievable” and “phenomenal,” they were uniformly ecstatic at hearing the band. While every aspect of the band’s performance impressed local fans, they particularly mentioned sound of the band, how clean, rounded, and uniform it was despite playing at volumes that often astonished local musicians. [33]

In one particular tale related in Dennis Huggard’s booklet Artie Shaw in New Zealand — 1943, one young soldier and jazz fan, David Commin, was on duty watch at the Wellington Winter Showgrounds camp when he went AWOL, and made his way to the Majestic Theater in Wellington central where the Shaw band was to play that day. According to his story, when he tried to purchase a ticket he discovered that they were sold out:

You can imagine how I felt. I turned to leave the theater, no doubt looking extremely downcast, when a U.S. officer approached me — I was only a lowly Private. “Did you wish to attend the concert, soldier?” I did not hesitate to assure him of my desire and my dashed hopes, to which he responded by presenting me with a ticket. That ticket entitled me to a seat in the centre of the front row of the dress circle. For the next two hours I was in seventh heaven, I couldn’t believe this was happening to me. Yes, I was caught getting back into camp, but it was worth the 14 days of CB [punishment duties] I received. [34]

For the musicians, however, Bert Peterson, Auckland columnist for Australian Music Maker and Dance Band News, summed it up best:

What an opportunity, and what a revelation! That music went right to the hearts of dance musicians...[Shaw’s] mastery of every phrase of the game is inspiring to behold, and the arrangements the band played put new life into every musician present. I guarantee all hands tore home to put in a few hours practice on the strength of it. Long-forgotten tutors, textbooks, and studies were rescued from the attic and thumbed anew. [35]

Conclusion

By the time the Shaw band left New Zealand for Australia on September 2, 1943, it had left a significant impression on the local jazz community. As Bert Peterson stated, musicians were reinvigorated and inspired by the band. Musicians were particularly inspired by the Shaw band’s performance practices and arranging, but they were also inspired by their professionalism and stage presence.

The effects of the Shaw band’s tour would begin to appear in the latter stages of the war, and would continue into the post war decade as New Zealand musicians put the performance practices that they witnessed into action. [36] Musicians attempted to emulate aspects of favorite band members’ sound and technique, especially those of tenor saxophonist Sam Donahue, trumpeter Max Kaminsky, and drummer Dave Tough. However, local clarinetists chose not to attempt emulation of Artie Shaw — his sound was so distinctive that they felt they would never be able to do more than a poor imitation. [37]

The wider communities of Auckland and Wellington apparently made their own impact on band members, as several musicians later stated in interviews, articles, and memoirs how much they enjoyed their welcome and tour of New Zealand, despite their hectic schedule. Pianist Rocky Coluccio told Dennis Huggard:

The people in Auckland were unusually warm and friendly. The ladies were wonderful. Despite the concerts and dances played, it was more like a rest and rehabilitation situation for the band. After the New Hebrides, Solomons, and New Caledonia, the food seemed like manna from heaven. [38]

Bibliography

Books

- Avery, Ken. Where are the Camels? A New Zealand Dance Band Diary. Wellington: First Edition, 2010.

- Belich, James. Paradise Reforged: A History of New Zealanders from the 1880s to the Year 2000. Auckland: Penguin Press, 2001.

- Bevan, Denys. United States Forces in New Zealand 1942–1945. Alexandra, N.Z.: Macpherson, 1992.

- Bioletti, Harry. The Yanks are Coming: The American Invasion of New Zealand 1942–1944. Century Hutchinson: Auckland, 1989.

- Bourke, Chris. Blue Smoke: The Lost Dawn of New Zealand Popular Music 1918–1964. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2010.

- Huggard, Dennis O. Artie Shaw in New Zealand 1943. New Zealand Series 15. Auckland: D. Huggard, 2007.

- McGibbon, Ian. New Zealand and the Second World War: The People, the Battles and the Legacy. Auckland: Hodder Moa Beckett, 2004.

- Parr, Alison. Home: Civilian New Zealanders Remember the Second World War. Auckland: Penguin, 2010.

- Phillips, Jock, and Ellen Ellis. Brief Encounter: American Forces and the New Zealand People 1942–1945. Wellington: Historical Branch, Department of Internal Affairs, 1992.

- Taylor, Nancy M. The New Zealand People at War: The Home Front. Vol. 1. Wellington: Department of Internal Affairs, 1986.

- White, Georgina. Light Fantastic: Dance Floor Courtship in New Zealand. Auckland: HarperCollins, 2007.

Magazines and Newspapers

- Auckland Star

- Australian Music Maker and Dance Band News

- Australian Record and Music Review

- Evening Post

- Jukebox: New Zealand’s Swing Magazine

- New Zealand Herald

References

[1] Richard Wang, “Shaw, Artie.” In Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/25599 (accessed July 3, 2012).

[2] Denys Bevan, United States Forces in New Zealand 1942–1945 (Alexandra, N.Z.: Macpherson, 1992), 22–27.

[3] The population of New Zealand at the last pre-war census in 1936 was 1,573,810. “Total Population, figure 1,” Te Ara: An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand, 1966, http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/1966/population/4 (accessed July 2, 2012). Harry Bioletti, The Yanks are Coming: The American Invasion of New Zealand 1942–1944 (Century Hutchinson: Auckland, 1989), 35. Nancy M. Taylor, The New Zealand People at War: The Home Front, vol. 1, (Wellington: Department of Internal Affairs, 1986), 633. There is a great disparity between the estimates of Bioletti (500,000) and Taylor (100,000), however both couch their estimates with the term “about” or “approximately.” It is clear that neither were working from established data. It is also possible that Taylor did not include the Naval personnel who lived on board their ships while stationed in New Zealand.

[4] Alison Parr, Home: Civilian New Zealanders Remember the Second World War (Auckland: Penguin, 2010), 23–25, 128–150; James Belich, Paradise Reforged: A History of the New Zealanders from the 1880s to the Year 2000 (Auckland: Penguin, 2001), 292–294.

[5] Parr, Home, 84–87; Ian McGibbon, New Zealand and the Second World War: The People, the Battles and the Legacy (Auckland: Hodder Moa Beckett, 2004), 158–160.

[6] James Belich, Paradise Reforged, 272–275, 287–288.

[7] Jock Phillips and Ellen Ellis, Brief Encounter: American Forces and the New Zealand People, 1942–1945 (Wellington: Historical Branch, Department of Internal Affairs, 1992).

[8] Bert Peterson, “Artie Shaw Makes History at Auckland,” Australian Music Maker and Dance Band News September 1943 [sourced from Artie Shaw File (clippings), Dennis Huggard Jazz Archive (Alexander Turnbull Library) MS–Papers–9018–60]; Harold S. Kaye, “The Artie Shaw Navy Band in New Zealand,” Australian Record and Music Review (October 1991).

[9] Belich, Paradise Reforged, 289; Bevan, United States Forces in New Zealand, 370–371.

[10] “Band Leader’s Visit: American Orchestra Tour of New Zealand,” New Zealand Herald, July 31, 1943; “Welcome Home Ball,” Evening Post, August 16, 1943; “Returned Men,” Evening Post, August 23, 1943.

[11] “Band Leader’s Visit,” New Zealand Herald, July 31, 1943; “Band Tours New Zealand: Artie Shaw plays for Marines and at City Dances,” New York Times, August 29, 1943.

[12] Chris Bourke, Blue Smoke: The Lost Dawn of New Zealand Popular Music 1918–1964 (Auckland: University of Auckland Press, 2010), 129; Dennis Huggard, Artie Shaw in New Zealand 1943, New Zealand Series Booklet 15 (Auckland: D. Huggard, 2007), unpaginated, 1 August.

[13] Chris Bourke, Blue Smoke, 129.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Bourke, Blue Smoke 129; Huggard, Artie Shaw in New Zealand, unpaginated, various dates.

[16] A note about Maori pronunciation: while there are numerous dialects, the Maori language is broadly phonetic when written, with the exception of the diphthongs (such as ng, ai, and wh), and the use of glottal stops. Thus Rongotai can be pronounced “Rong-o-tie” [ɾɔŋɔʈɪ] and Whangarei, “Fung-r-a” [faŋaˈɾɛi].

[17] Huggard, Artie Shaw in New Zealand, unpaginated, 15 August; Bevan, United States Forces in New Zealand, 356; “Welcome Home Ball,” Evening Post, August 16, 1943.

[18] “Welcome Home Ball,” Evening Post, August 16, 1943; “Returned Men,” Evening Post, August 23, 1943; “Blues for Business but Beethoven for Pleasure,” New Zealand Listener, August 27, 1943.

[19] Huggard, Artie Shaw in New Zealand, unpaginated, 30 August.

[20] Georgina White, Light Fantastic: Dance Floor Courtship in New Zealand (Auckland: HarperCollins, 2007), 105; “Auckland Plans Town Hall Function: Large Crowd Expected,” New Zealand Herald, September 1, 1943; “Call at Dance: Red Cross Function, Cheers from Servicemen,” New Zealand Herald, September 2, 1943.

[21] Huggard, Artie Shaw in New Zealand, unpaginated, 1 September.

[22] An informative title might simply be “When the Ships Come In,” particularly if such a broadcast happened to coincide with a military ship arriving in port.

[23] “Swing Music,” New Zealand Observer, August 4, 1943.

[24] Dennis Huggard Jazz Archive (Alexander Turnbull Library) MSD10–0705.

[25] Email communication with Bruce Talbot, February 12, 2008.

[26] Peterson, “Artie Shaw Makes History,” Australian Music Maker and Dance Band News, September 1943.

[27] Bourke, Blue Smoke, 129; Huggard, Artie Shaw in New Zealand, unpaginated, 13 August.

[28] Bourke, Blue Smoke, 129.

[29] Huggard, Artie Shaw in New Zealand, unpaginated, 9 August. I believe the dances in question were the Naval dance on August 6 and the Marine Aviation dance on August 7; “New Zealand Soldiers Guests of U.S. Navy,” Auckland Star, August 7, 1943.

[30] Bourke, Blue Smoke, 129.

[31] E. J. Wansbone, “Rosoman Reminisces,” Jukebox: New Zealand’s Swing Magazine, March 1947, 3.

[32] Bourke, Blue Smoke, 129–130.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Huggard, Artie Shaw in New Zealand, unpaginated, “A Day to Remember by David Commin.”

[35] Peterson, “Artie Shaw Makes History.” Note also that in New Zealand until the latter 1950s, jazz musicians most often termed themselves “dance musicians,” because their primary employment was in dance bands and the primary venues for performance were dance halls or cabarets.

[36] Dale Alderton, interview by Aleisha Ward, 2002.

[37] Ken Avery, Where are the Camels? A New Zealand Dance Band Diary (Wellington: First Edition, 2010), 22.

[38] Huggard, Artie Shaw in New Zealand, unpaginated, 31 August.

Author Information:

In 2003, Aleisha Ward was one of the first graduates of the Bachelor of Music in Jazz Performance at the University of Auckland, New Zealand. She holds a Masters of Arts degree in Jazz History and Research from Rutgers University, New Jersey and recently completed a PhD in music at the University of Auckland, focusing on jazz in New Zealand 1920–1955.

Abstract:

This article aims to illuminate a small portion of Artie Shaw’s 1943 tour, chronicling the month he spent entertaining military personnel and civilians in New Zealand, and revealing aspects of the impact that the Shaw band had on the local jazz scene.

Keywords:

Artie Shaw, New Zealand, World War II, jazz

How to cite this article:

- Chicago 15th ed.: Ward, Aleisha. “Artie Shaw in New Zealand.” Current Research in Jazz 5, (2013).

- MLA 7th ed.: Ward, Aleisha. “Artie Shaw in New Zealand.” Current Research in Jazz 5 (2013). Web. [date of access]

- APA 6th ed.: Ward, A. (2013). Artie Shaw in New Zealand. Current Research in Jazz, 5 Retrieved from http://www.crj-online.org/

For further information, please contact: